Deceased organ and tissue donation after medical assistance in dying and other conscious and competent donors: guidance for policy

PDF copies of the following report are available by request. Submit a request by sending an email to OTDT@blood.ca, please include the title and use the subject line: PDF Document Request.

Foreword

In Canada, organ donation from deceased donors is a common practice that saves or improves the lives of more than 2,000 Canadians every year, accounting for more than 3 out of 4 transplanted organs.1 Deceased donation is permitted following either neurological or circulatory determination of death. Donation following neurological determination of death (DNDD) is more common in Canada, but rates of DNDD have remained largely stable over the past decade. Donation following circulatory determination of death (DCDD) was historically considered more controversial than DNDD, but DCDD has become increasingly common, accounting for 23 per cent of all organs donated in Canada in 2016.1 The practice of DCDD is also evolving; the DCDD guidelines developed in 2005 addressed the conventional scenario of an unconscious, incapable, critically ill patient who was not expected to survive after the withdrawal of life-sustaining measures (WLSM).2

However, two recent developments have led to scenarios that raise practical and ethical issues that are not clearly addressed in the 2006 guideline. First, as a result of the Supreme Court of Canada’s decision in the case of Carter vs. Canada3, and the passing of Bill C-14 by the Canadian parliament3,4 and Bill 52 in Quebec5, eligible Canadian patients suffering from terminal illnesses may now seek medical assistance in dying (MAID) as a means of ending their lives under the supervision of a medical or nurse practitioner. Second, there has been an anecdotal increase in requests for organ donation by patients with progressive neuromuscular diseases who are dependent on mechanical ventilation (invasive or non-invasive) and who have made the decision to withdraw life-sustaining measures. These two scenarios differ from the conventional DCDD scenario in that the donors are conscious and competent and, therefore, able to give first-person consent for both the decision to withdraw life-sustaining measures and the decision to donate their organs. These scenarios can be challenging emotionally and morally for health care teams and they can raise unprecedented ethical and practical challenges for patients, families, professionals, institutions, and society.

Prompted by individual cases and requests from patients, Canadian practitioners have requested guidance for policy development to manage organ donation in these conscious competent patients. In response to this request, Canadian Blood Services, in consultation with the Canadian Neurological Sciences Federation and in collaboration with the Canadian Critical Care Society, the Canadian Society of Transplantation, and the Canadian Association of Critical Care Nurses, convened to provide bioethical, legal, and clinical guidance for guidance about managing deceased organ and tissue donation for conscious competent patients.

Executive Summary

Purpose and objectives of the workshop

Canadian Blood Services hosted a forum in Toronto on May 15 and 16, 2017. The two-day forum brought together medical, legal, and bioethics experts, as well as patients, from across Canada. The goal of this forum was to develop expert guidance for clinicians, donation program/organ donation organization (ODO) administrators, end-of-life (EOL) care experts, MAID providers and policy makers regarding organ and tissue donation from a conscious and competent patient. The forum objectives were to:

- Analyze organ and tissue donation in the conscious competent patient from legal, medical, and ethical perspectives.

- Develop and publish expert guidance for offering organ and tissue donation to patients who have made a decision that will lead to imminent death:

a. Conscious competent patients who have chosen to withdraw mechanical ventilation (includes invasive and non-invasive forms of ventilation.

b. Conscious competent patients who have chosen to withdraw extracorporeal support including ECMO (extracorporeal membrane oxygenation) and/or other mechanical circulatory support.

c. Eligible patients who have requested MAID (as defined as death by injection). - Develop a knowledge translation strategy that includes all relevant stakeholders.

- Identify questions for research.

Summary of recommendations

Deceased organ donation in conscious and competent patients

1. Medically suitable, conscious and competent patients who provide first person consent to end-of-life procedures should be given the opportunity to donate organs and tissues. Patients who seek MAID or WLSM should not be prohibited from donating organs and tissues.

2. Before consenting to WLSM or MAID, patients should carefully consider all end-of-life options with their physician or health care professional.

Referral to an organ donation organization

3. Referral to the organ donation organization should occur as soon as is practical after the decision to proceed with WLSM or determination of eligibility for MAID. Preliminary evaluation of the patient’s eligibility to donate should be performed prior to the donation approach, if possible. This avoids the potential distress of making a request or obtaining consent for donation only to have to inform the patient that they are medically or logistically ineligible.

Conversations about donation

4. The decision to proceed with MAID or WLSM must be separate from, and must precede, the decision to donate.

5. Treating physicians, MAID providers, and MAID assessors should be educated on how to respond to inquiries concerning organ donation. This should include how the decision to donate may affect the end-of-life care process and options, and when to refer patients to the organ donation organization. The organ donation organizations should develop checklists or discussion guides to facilitate donation conversations to ensure patients are consistently well informed.

6. All eligible, medically suitable patients should be given an opportunity to consider organ and tissue donation, consistent with provincial or territorial required referral legislation, regional policy, and ethical principles of respect for autonomy and self-determination. However, this must be reconciled with regional values and health care culture. Initially, some jurisdictions might prefer to begin with systems that respond only to patient-initiated requests.

7. Donation coordinators will have to tailor their conversations to ensure the patient remains the centre of the MAID or WLSM and organ donation process, to ensure patient autonomy.

8. When an approach is to be made, discussions should happen early to allow individuals time to consider the options, ask questions, and to plan accordingly.

9. Patients and their families should be provided with standardized information resources, such as online material or pamphlets to help guide responses to donation inquiries. The decision to proceed with MAID or WLSM must precede discussions about donation.

Consent

10. The patient must have the ability to provide first-person consent to MAID or WLSM as well as to organ and or tissue donation.

11. Physicians, MAID assessors, and WLSM or MAID providers should be cognizant of the risk of coercion or undue influence on patients to donate their organs; however, the patient’s altruistic intentions should not be discouraged.

12. Donation discussions must respect patient autonomy and first-person consent should be obtained and upheld. Although it is welcomed and encouraged that family members are included in donation conversations, consent must be obtained from the patient and conversations should be focused on them.

13. The individual should be informed and understand that they may withdraw consent for MAID or donation at any time, and that withdrawal of consent for donation does not affect their consent for, or access to, MAID or WLSM.

14. The donation team should make every effort to resolve conflict, through dialogue, between the patient’s expressed wishes to donate and a family’s disagreement. First-person consent should direct all subsequent decisions unless consent was revoked.

15. If a conscious and competent patient provides first-person consent to donate after WLSM but subsequently loses decisional capacity, there is a strong case for proceeding with donation after WLSM because the patient was adequately informed about the decision by a trained donation expert and gave consent in the context of their illness7

and an anticipated imminent death. However, if a patient loses capacity prior to the MAID procedure, then MAID procedures cannot be carried out.

16. The donation team must understand and abide by the laws and policies of their jurisdiction with respect to reporting of MAID deaths (e.g. coroner, special committee). To facilitate donation, these parties should be contacted prior to the MAID procedure, in accordance with the current laws and policies.

Donor testing and evaluation

17. Primary care physicians, and staff or organ donation organizations, MAID providers and transplant teams should work to minimize the impact and inconvenience to the patient of donating their organs. This could include scheduling home visits for blood draws and coordinating investigations (e.g. x-rays, ultrasound) to minimize hospital visits and inconvenience to the individual.

18. Transplant teams and surgeons should work with the donation team to determine the minimum necessary investigations, to avoid the burden of excessive assessments and testing.

19. Donor teams should routinely discuss the potential impact of unanticipated results from the donor investigations, including previously undiagnosed infectious diseases, and their impact on public health reporting and contact tracing.

MAID procedures

20. Consent for MAID must be reaffirmed prior to the MAID procedure. The health care team or MAID provider should reaffirm consent prior to relocation to the hospital and prior to beginning any antemortem interventions for the purposes of facilitating donation. This may reduce the momentum of the donation process and reduce the potential for patients to feel pressured to continue with MAID in the interest of ensuring organ donation.

Determination of death

21. The dead donor rule must always be respected. Vital organs can only be procured only from a donor who is already deceased; the act of procurement cannot be the immediate cause of death.

22. For determination of death, absence of a palpable pulse alone, is not sufficient. If arterial monitoring is not available, alternate means of determining absence of anterograde circulation should be used in conjunction with absence of a palpable pulse, such as a carotid perfusion ultrasound, Doppler monitoring, aortic valve ultrasound or an isoelectric EKG to determine asystole.

23. As with all cases of DCDD, death should be confirmed by a second physician after a 5-minute ‘no touch’ period of continuous observation during which time no donor-based interventions are permitted.8

Protection for patients

Separation of decisions

24. To avoid any real or perceived conflict of commitment, health care practitioners should separate the decision regarding WLSM or MAID from discussions concerning donation. Providers who are assessing eligibility for MAID should not be involved in donation discussions. Discussions concerning donation should happen only after WLSM decisions are made, or patients have been found eligible for MAID by 2 independent assessments.

25. The primary health care team should acknowledge patient inquiries concerning donation that are made prior to a decision to proceed with MAID or WLSM. General information on deceased organ and tissue donation may be provided. However, specific discussion and decisions pertaining to donation should wait until the decision to proceed with MAID or WLSM has been finalized.

26. Patients may wish to postpone their MAID procedure, owing to a temporary improvement in their health or an event they wish to experience prior to their death. The freedom of the patient to postpone their MAID procedure must be reinforced and preserved and every effort should be made to honor their wishes to donate their organs should their MAID procedure be rescheduled.

Directed and conditional donation

27. No restrictions should be placed on potential organ recipients. Directed deceased donation (direction of a patient’s organs to a specific recipient) or conditional donation (e.g. organs will be donated only if the patient can place conditions on what social groups may or may not access them) from patients considering MAID or WLSM should be neither offered nor encouraged.

28. Living donation prior to death from patients considering MAID or WLSM should be neither offered nor encouraged.

29. Should a patient insist on directed deceased donation or living donation prior to death, the request should be considered on a case-by-case basis.

Separation of roles

30. Consistent with current guidelines and practice regarding DCDD, separation should be maintained between the EOL care, donation, and transplant teams. Surgical recovery and transplant teams should not be involved in the patient’s end-of-life care or MAID or WLSM procedure. The only exception is insofar as they may provide guidance for minimal requirements for donor investigations or premortem interventions.

31. Patients who wish to donate their organs after MAID or WLSM, but who request that their decision to pursue MAID/WLSM remain confidential, should be informed of the risk that their family members may discover incisions associated with surgical retrieval of organs. They should be encouraged to disclose their decision to family members; however, there is no obligation to stop the donation process should the patient wish to maintain the confidentiality of their MAID or WLSM procedure.

32. That an organ donor received MAID should not be disclosed to the potential recipient during allocation; however, medically relevant information regarding their underlying disease may be disclosed according to guidelines for exceptional distribution, where applicable.

Supports for patients and families

33. Specially trained professionals, such as donation physicians and coordinators, patient navigators, or social workers, must be available to answer the patient’s questions and facilitate the coordination of their MAID or WLSM and donation. This may take place over a period of many weeks. The patient and their family must be provided with specific instructions on how to access these resources.

34. Support should be available in an optimally convenient location and setting for the patient, such as home visits or coordination with visits to clinics. For patients in remote locations, video-based technologies may be of assistance.

35. The donation team should work with the patient, their family, and the MAID or WLSM provider to develop a plan and best possible options for the MAID or WLSM procedure that accommodates the wishes of the patient, preserving the opportunity to donate and reconciling coordination of hospital logistics.

36. Ongoing access to support for patients and their families is critical. Despite patient consent, donation might not proceed due to failure to find a suitable recipient, deterioration of health that compromises medical eligibility to donate, surgical findings during organ recovery, or withdrawal of consent by the patient. These patients and their families must continue to receive support even if donation does not proceed.

37. Continued support must be available to family members after the patient’s death. Processes need to be developed to ensure families are given the opportunity to provide feedback on their experience, which may help with their grieving process and may help inform quality improvement measures.

Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) and neurodegenerative diseases

38. People with ALS and patients with other non-transmissible neurodegenerative diseases should be offered the opportunity to donate organs after their death.

39. ODOs should exercise caution regarding allocation of organs from donors with undiagnosed or rapidly progressive neurodegenerative diseases, as these may pose elevated risks to recipients. Organ allocation in this context should follow existing exceptional distribution policies and practices.

40. Transplant professionals must balance the benefits of the transplant against any potential for harm of receiving a transplant of an organ from a donor with a neurological illness. Transplant professionals must use their discretion to help the transplant candidate navigate the decision. The surgeon may wish to consult the donor’s neurologist to help inform their advice to the transplant candidate.

41. All cases of ALS or other neurodegenerative diseases that arise in transplant recipients should be reported to Health Canada to determine potential associations with donor illness and baseline risk of neurodegenerative illness in transplant recipients (e.g. whether transplant recipients, in general, have rates of ALS that differ from the general population).

42. Physicians who follow organ recipients should be: aware that the donation was by a patient with neurodegenerative disease such as ALS, aware of theoretical transmission risk of neurodegenerative diseases, and cognizant of symptoms or complaints that warrant further investigation by a neurologist to determine if a neurodegenerative disease is present.

43. Active monitoring (i.e., regular visits to a neurologist) is NOT recommended for transplant recipients who have received an organ from a donor with a neurodegenerative disease. Neurological monitoring would impose a substantial burden on the recipient and present no benefit to the recipient, particularly as there is currently no value in early detection of these illnesses.

44. Information resources should be available for transplant candidates and for transplant professionals to help with the decision regarding whether to accept or refuse an organ for transplant. A means of obtaining a consult from a specialist neurologist in neurodegeneration may also be useful in helping the potential recipient make an informed decision. This information should also be available to ODOs and the donation professionals responsible for assessing the eligibility of the patient who is considering donation.

Health care professionals

45. Health care professionals may exercise a conscientious objection to MAID or WLSM specifically, but they should strive to accommodate the wishes of the donor by ensuring that their objection to MAID or WLSM does not impede the ability of the patient to donate.

46. Health care professionals should act in accordance with provincial and territorial requirements as well as professional and regulatory college requirements for effective referral.

47. Health care professionals responsible for the care of conscious, competent patients who have requested WLSM or MAID and donation should be briefed so they are familiar with the patient’s end-of-life plan and relevant policies and procedures.

48. Debriefing after the procedure (i.e., MAID or WLSM with or without donation) should be offered every time to all members of the health care team who participated. Debriefing by an external resource may be beneficial so that team members feel comfortable sharing their experience.

49. Psychological support, such as that offered through employee assistance plans (EAP), should be accessed when required. Staff of employee assistance plans may benefit from additional training and education regarding MAID with or without donation to adequately meet the needs of these health care professionals.

50. Hospitals must ensure that staff are available who are willing and able to honor the patient’s wishes to donate after their death or have an effective referral plan in place.

51. Participation of health care professionals in MAID and in organ donation by patients who received MAID should be voluntary, when possible, without interfering with the patient’s access to care. The health care team should be well informed and well briefed so that they understand the patient’s wishes and the outcome they are working towards as well as relevant policies and procedures.

Reporting

52. Clinicians must be aware of the reporting and documentation requirements for MAID and WLSM and for donation in their jurisdiction.

53. Records pertaining to organ donation after MAID, as well as donation and transplant outcomes, should be reported federally and be accessible to clinicians, researchers, and administrators. Transplant outcomes should be easily cross-referenced with the underlying illness of the MAID donor.

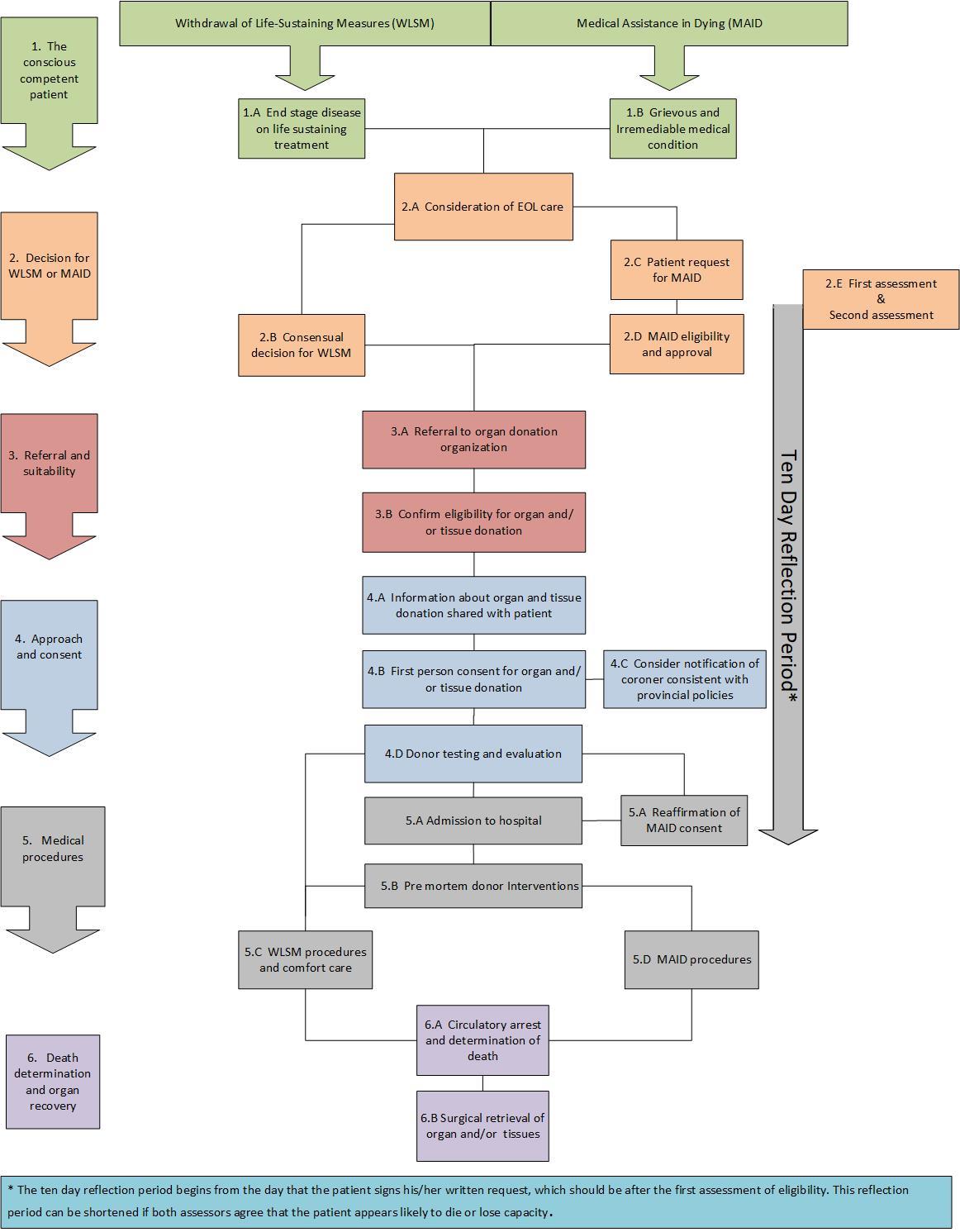

Figure 1 outlines the clinical pathway for organ donation in conscious competent patients.

Overview

A. Workshop Overview

In order to gather perspectives and insight from multiple stakeholders across Canada, Canadian Blood Services hosted a workshop in Toronto on May 15 and 16, 2017. The two-day forum brought together medical, legal, and bioethics experts, as well as patients, from across Canada. The goal of this forum was to develop expert guidance for clinicians, donation program/organ donation organization (ODO) administrators, end-of-life (EOL) care experts, MAID providers and policy makers regarding organ and tissue donation from a conscious and competent patient. The workshop agenda and background documents are provided in Appendices 3 to 8.

Purpose and objectives

1) Analyze organ and tissue donation in the conscious competent patient from legal, medical, and ethical perspectives.

2) Develop and publish expert guidance for offering organ and tissue donation to patients who have made a decision that will lead to imminent death:

a. Conscious competent patients who have chosen to withdraw mechanical ventilation (includes invasive and non-invasive mechanical ventilation).

b. Conscious competent patients who have chosen to withdraw extracorporeal support including ECMO and/or other mechanical circulatory support.

c. Eligible patients who have requested MAID.

3) Develop a knowledge translation strategy that includes all relevant stakeholders.

4) Identify questions for research.

Planning committee and key contributors

The planning committee members are noted below. See Appendix 2 for a full list of workshop participants.

Ms. Amber Appleby, Associate Director, Canadian Blood Services

Dr. Daniel Z. Buchman, Bioethicist, University Health Network, Member, Joint Centre for Bioethics, Assistant Professor, Dalla Lana School of Public Health, University of Toronto

Dr. James Downar, Co-chair, Critical Care and Palliative Care Physician, University Health Network and Sinai Health System, Associate Professor, Department of Medicine, University of Toronto, Chair, Ethical Affairs Committee, Canadian Critical Care Society

Dr. Marie-Chantal Fortin, Associate Professor, Bioethics Program, Department of Social and Preventive Medicine, École de santé publique de l’Université de Montréal

Researcher, Nephrology and Transplantation Division, Centre de recherche du Centre hospitalier de l’Université de Montréal (CRCHUM), Chair, Ethics Committee, Canadian Society of Transplantation

Mr. Clay Gillrie, Senior Program Manager, Canadian Blood Services

Dr. Aviva Goldberg, Head Pediatric Nephrologist, Department of Pediatrics and Child Health, University of Manitoba, Clinical Ethicist, University of Manitoba

Director, Canadian Society of Transplantation

Ms. Vanessa Gruben, Associate Professor, Faculty of Law, University of Ottawa, Member, Centre for Health Law, Policy and Ethics

Ms. Jehan Lalani, Program Manager, Canadian Blood Services

Dr. Michael D. Sharpe, Co-chair, Intensivist, London Health Sciences Centre, Professor, Department of Anesthesia and Perioperative Medicine, Schulich School of Medicine, University of Western Ontario, Treasurer, Canadian Critical Care Society

Dr. Sam D. Shemie, Project Medical Advisor, Process Consultant and Workshop Facilitator, Division of Pediatric Critical Care Montreal Children's Hospital McGill University Health Centre and Research Institute, Professor of Pediatrics, McGill University, Medical Advisor, Deceased Donation, Canadian Blood Services

Dr. Christen Shoesmith, Neurologist, Medical Director, London Health Sciences Centre ALS Clinic, Assistant Professor, Clinical Neurological Sciences, Western University

Member, Canadian Neurological Sciences Federation, International expert

Dr. Dirk Ysebaert, Vice-Dean, Faculty of Medicine, University of Antwerp, Director, Department of Hepatobiliary, Transplantation and Endocrine Surgery, Antwerp Transplant Center. Dr. Ysebaert is Head of the Department of Hepatobiliary, Transplantation and Endocrine Surgery, Antwerp University Hospital. Dr. Ysebaert is Professor of Surgery, Antwerp Surgical Training and Research Center (ASTARC) at the Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences (Antwerp University). He has served as president and vice president of the Belgian Society for Transplantation, Councilor for the European Society for Organ Transplantation, and as a board member for the Eurotransplant International Foundation. Dr. Ysebaert has over one hundred publications, including the euthanasia and organ donation experience in Belgium.

Stakeholders

Stakeholders are individuals, groups, and organizations with a significant stake in the purpose, objectives, and outcomes of this process. It is important to consider the impact of recommendations on several stakeholder constituencies. For the purposes of the project, we considered the potential impacts on the following stakeholder groups (listed in alphabetical order):

• Coroners and Medical Examiners

• Health authorities, governments, and policy-makers

• Health care professionals and administrators who are involved in critical care, emergency medicine, neurology

• Health care professionals who care for dying patients and administrators with responsibility for the program

• Institutions, e.g., hospitals, health care regions

• MAID providers and assessors

• Organ Donation Organizations (ODO), donation personnel, health care professionals and administrators who may take part in the donation process

• Partners in the leading practice development process

• Patients and society-at-large

• Research funders and organizations

In scope

1) Controlled DCDD in patients with the following features:

a. Awake, conscious and competent;

b. Adults or mature minors;

c. Ability to provide first-person informed consent to make their own treatment and/or end-of-life (EOL) decisions; and

d. Have chosen an EOL care intervention that would lead to imminent death:

i. Withdrawal of life-sustaining measures, or

ii. Medical assistance in dying consistent with existing or evolving federal and provincial legislation.

2) Pathogenesis and transmissibility of illnesses that would make a patient eligible for MAID or WLSM with influence on medical eligibility for organ donation.

3) Ethical implications and potential outcomes of allowing organ and tissue donation by these patients.

4) Education and training requirements for health care professionals.

5) Public and patient awareness.

Out of scope

1) Ethics of MAID or WLSM

2) Best practices for MAID or WLSM independent of organ and tissue donation.

3) Donation by euthanasia (i.e. organ donation that does not adhere to the dead donor rule).

4) Living organ donation.

Assumptions and key considerations

1) Organ donation and transplantation is broadly accepted and supported by workshop participants and the Canadian public; organ donation and transplantation benefits society.

2) Current Canadian controlled DCDD guidelines2 do not sufficiently address the management of conscious competent patients.

3) Requests for organ and tissue donation by conscious competent patients requires clinical, bioethical and legal guidance.

4) Optimal care of the dying patient is the priority of health care workers.

5) Decisions made via first person informed consent are the highest standard of decision making for treatment and EOL care.

6) Consistent with existing laws and practices, deceased organ donation must adhere to the dead donor rule.

7) Professional integrity should always be maintained. Health care providers are guided by their own values and beliefs as well as professional values and practice standards.

B. Workshop Process

Prior to the workshop, the planning committee commissioned a survey, performed literature searches, and developed background documents to guide and support discussion on the following topics:

1) Canadian attitudes towards organ and tissue donation by conscious competent patients; Appendix 3 - IPSOS Public Survey

2) Requests for organ donation by conscious, competent patients; Appendix 4 – Gruben, Yazdami, and Goldberg

3) Pathogenesis and potential transmissibility of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis; Appendix 5 - Shoesmith

4) Conscientious objection as it relates to donation after MAID; Appendix 6 – Buchman and Gruben

The workshop was structured around plenary presentations by Canadian and international clinicians, organ donation and transplantation ethicists and legal experts, a coroner, and patient partners. See Appendix 7 for full agenda.

Attendees were divided into smaller groups throughout the meeting to discuss and make recommendations regarding specific challenge questions that were informed by fact sheets and expert presentations. See Appendix 8 for fact sheets and challenge questions. Key points and conclusions from these groups were then shared in plenary.

Withdrawal of life-sustaining measures and controlled donation after circulatory determination of death

The majority of controlled DCDD cases occur after acute devastating brain injury. In such cases, the patient is unconscious and, thus, not competent to participate in their own EOL care decisions. While intent to donate decisions may have been registered or indicated in advance, decisions concerning EOL care, WLSM and donation are made by the patient’s substitute decision maker (SDM) in consultation with the health care team.

There are other groups of patients with illnesses that are incurable and terminal but are not associated with devastating brain injury. These patients may be conscious, competent, and capable of actively participating in decisions about their EOL care, including decisions for WLSM or MAID, as well as consenting to organ donation.

WLSM is the most common event preceding death in Canadian intensive care units6 and is a step in the clinical pathway of nearly all DCDD organ donors. The decision by the patient’s SDM to withdraw treatment is based on poor prognosis, concern for the patient’s suffering, and/or poor future quality of life7 and should be consistent with the patient’s values and/or prior expressed wishes.

While many of these patients may be eligible to donate organs, there are several barriers to organ donation in this population. These include a failure to identify a potential donor; failures on behalf of the health care team to approach SDMs for authorization for donation, refusal of authorization by the family or SDM, death not occurring in a specified time period that allows suitable organs for transplantation and lack of resources for surgical retrieval of organs and transplantation.8 Only about 2 per cent of in-hospital deaths may be considered potential donors and, of these, only one in six will actually donate an organ.8

Medical assistance in dying

The legal landscape around MAID has evolved rapidly in Canada following the Supreme Court decision that prohibitions in the Criminal Code of Canada were unconstitutional and the passing of legislation, first in Quebec5 and then by the Federal Government of Canada4, permitting MAID under certain circumstances. Specifically, the patient must have a “grievous and irremediable medical condition”, defined by the following criteria:

a) they have a serious and incurable illness, disease or disability;

b) they are in an advanced state of irreversible decline in capability;

c) that illness, disease or disability or that state of decline causes them enduring physical or psychological suffering that is intolerable to them and that cannot be relieved under conditions that they consider acceptable; and

d) their natural death has become reasonably foreseeable, taking into account all of their medical circumstances, without a prognosis necessarily having been made as to the specific length of time that they have remaining. (1 s. 241.2(2) of the Criminal Code of Canada.)

Early demographics for MAID

Statistics for MAID cases in Canada at the time this forum occurred were available from the period July 1, 2016 to Dec. 31, 2016 (Dec. 10, 2015 to Dec. 31, 2016 for Quebec) and are summarized in Table 1. Nearly half of all the assisted deaths – 463 – took place in Quebec, where a separate end-of-life law took effect on Dec. 10, 2015, six months before the federal law came into effect. Compared with other countries9-11, the early experience in Canada is notable for an underrepresentation of cancer patients and a higher incidence in patients with chronic neurological conditions. Accordingly, Canada has the highest rates of multiple sclerosis in the world.12

It is unclear if this early trend of MAID in Canadian patients with chronic neurological conditions will continue, as it may be due to an initial overrepresentation of patients with chronic (non-cancer) illnesses who were waiting for MAID to become available to them. Patients seeking MAID for terminal cancer are often not medically eligible to become donors; therefore, those who comprise the pool of potential donors among MAID patients have underlying illnesses within the other categories.

Table 1. Demographics of MAID

| Cause of Death | Netherlands9 | Belgium10 | US*11 | Canada |

| Cancer | 79% | 80% | 80% | 57% |

| Cardiovascular | 4% | 4% | 3% | 11% (combined with Respiratory) |

| Respiratory | 16% (combined with Neurological, Other) | 5% | 4% | see above |

| Neurological | see above | 7% | 8% | 23% |

| "Other" | see above | 4% | 5% | 8% |

| Annual Cases (cases/million) | 3800 (224) | 2800 (247) | 100 (0.3) | 970 (27) |

*Euthanasia is illegal in the United States and assisted suicide is only permitted in some states, therefore organ donation is not possible.

Rationale for donation after MAID and WLSM

A review of the literature found support for offering the opportunity to donate organs after death to patients seeking MAID or WLSM, while also highlighting some ethical concerns as illustrated below in Table 2.

Table 2. Rationales for and against deceased organ donation following MAID/WLSM (adapted from Shaw DM13)

| Rationale in support of organ donation following MAID/WLSM |

|

| Concerns about organ donation following MAID/WLSM |

|

Public perception

In September 2016, Canadian Blood Services commissioned IPSOS to conduct a survey of Canadian adults (n = 1,006) concerning their attitudes towards organ donation in competent conscious patients:

- 92 per cent approve of people donating their organs at the time of their death

- Strong support for conscious competent patients donating their organs after WLSM (87%) or MAID (80%)

- Significantly more oppose donation after MAID (12%) than after WLSM (6%)

- Concerns of those opposed to donation after WLSM/MAID include:

- Transmission of illness (48%)

- Pressure on vulnerable patients to choose WLSM or MAID sooner than they may have otherwise (46%)

- Pressure on vulnerable persons to donate their organs (43%)

- 80 per cent agree donation should be discussed with all patients regardless of illness or EOL decisions

- 83 per cent agree that the decision to donate organs should be confirmed prior to EOL care administration

- 53 per cent agree that donation should be discussed AFTER a decision has been made regarding EOL

- 25 per cent were undecided whether they would receive an organ from a donor following WLSM or MAID

These findings show that Canadians broadly support that conscious competent patients should be offered the opportunity to donate after MAID or WLSM; however, a minority of respondents were opposed to donation after MAID or WLSM citing concerns about transmission of illness to the recipient and pressure or coercion of the donating individual. See Appendix 3 for full report.

Donation after MAID – Early experience in Canada

Ontario, British Columbia and Quebec have the most experience with donation after MAID. As of April 2018, Ontario has performed eight organ donations, British Columbia has performed three, and Quebec has performed four donations. The Trillium Gift of Life Network Act in Ontario requires that Trillium Gift of Life (TGLN) be contacted when a patient’s death is imminent.29 This has been interpreted to require routine referral to the ODO of patients accessing MAID.30 In Quebec, the Commission de l’éthique en science et en technologie (CEST) and Transplant Quebec initially provided conflicting guidance on routine requesting in this context.14, 31, 32 Transplant Quebec initially discouraged raising donation with patients seeking MAID and, instead, offered donation only when patients make a ‘double request’, that is for MAID and for organ donation. Transplant Quebec has subsequently changed their policy and is now in agreement with routine requesting.

Anecdotally, some donor coordinators have reported comfort with the patient being able to express their own wishes and provide first person consent concerning donation; however, others have reported considerable emotional strain from these interactions. Transplant physicians and surgeons may have reservations about donation by conscious competent patients in both MAID and WLSM due to ethical concerns. Discomfort or misunderstanding with these circumstances may preclude transplantation.

Another challenge has been performing suitability assessments of potential donors. These tests (e.g. blood work, diagnostic imaging) are normally performed in hospital; however, many conscious competent patients are not hospitalized during this period and may have difficulty travelling for purposes of assessment due to their illness.

The ODOs/donation programs, transplant programs, clinical ethicists and bioethics committees, and clinicians across Canada have initiated work in developing processes to allow conscious competent patients to donate after WLSM or MAID; however, policies concerning eligibility of patients with neurodegenerative illnesses to donate, donor suitability assessments, permissibility of pre-mortem interventions, logistics and methods of death determination, continue to be the subject of discourse and evolving practice.

Donation after euthanasia in Belgium

Belgium legalized euthanasia in 2002, one year after the Netherlands. Patients eligible for euthanasia in Belgium must have a medical condition with constant and unbearable physical or mental pain, which cannot be relieved.26 Belgian law states: “The patient is an adult or an emancipated minor, capable and conscious at the time of his/her request. The request is made voluntarily, is well thought out and reiterated, and is not the result of outside pressure.”

Key differences from Canada’s legislation are that Belgium allows euthanasia for patients whose disease is not terminal, including mental illness, and for mature minors.

In Belgium, euthanasia and donation require separate decisions by the patient and are administered by separate health care personnel. Currently, patients are not actively approached as there is a concern of pressure or coercion, but patient-initiated requests are considered. Patient-initiated donation discussions may take place after permission for euthanasia has been granted.

Euthanasia must take place in hospital to allow for donation and the procedure takes place in or near an operating theatre to minimize ischemic time. While every effort is made to accommodate the wishes of the patient and their family and to ensure their comfort, some patients decline to donate, as they prefer to die at home.

Belgium considers donation after euthanasia to be a distinct category of DCDD and all cases in Belgium adhere to the dead donor rule. Procedures are performed by senior medical and nursing staff and their participation is voluntary.

In the donation-after-euthanasia process, heparin is administered directly after the euthanasia medications and death declaration is made by three clinicians. Determination of death is made clinically and there is no invasive monitoring required, preventing the need for invasive arterial blood pressure monitoring. A five-minute ‘no touch’ period is observed before organ retrieval begins. In the case of lung donation, the donor is intubated and ventilated following the five-minute ‘no touch’ period. Since the combination of drugs used for euthanasia is considered by some to be cardiotoxic, heart transplants are not currently possible following euthanasia in Belgium. Patients have expressed a strong desire to be able to donate their heart and there has been discussion, in the interest of patient autonomy, to develop strategies that would enable heart donation.

After the potential donor is assessed and medical eligibility is confirmed, Eurotransplant coordinates allocation four hours before the euthanasia procedure. Transplant centres are informed about the cause of death (i.e. that the donor had died by euthanasia). Eurotransplant allocation may take place between different countries; however, organs will not be allocated to patients in countries that do not accept donors who died by euthanasia. Furthermore, transplant candidates on the waitlist are able to indicate whether they would accept organs from donors after euthanasia. Directed donation is not permitted; however, Eurotransplant may inform transplant centres of a wish to direct donation and they may, at their discretion, allow the request to be facilitated even in cases where they may not have priority on the waitlist. There is no systematic monitoring of recipients for development of transmissible neurological illness in Belgium; however, adverse events are reported.

In 2015, euthanasia accounted for 2,022/110,508 deaths (1.8%) of all deaths in the country and there were eight donors after euthanasia accounting for 2.5 per cent of all deceased organ donors. Approximately 75 per cent of those receiving euthanasia were patients in the terminal phase of malignant disease and therefore not eligible to donate. From 2005-2015, 23 patients, with a mean age of 49.3 years, became organ donors after euthanasia. The underlying illnesses of these patients were neuropsychiatric disorders (n = 7), stroke/bleeding (n = 4), multiple sclerosis (n = 5), other neurodegenerative diseases (n = 10), and unbearable pain (n = 2). The mean time to circulatory arrest was 7.9 minutes and perfusion was initiated an average of 19.4 minutes after circulatory arrest. 33

As of 2015, 92 organs (45 kidneys, 21 livers, 16 lungs, 10 islets) were transplanted from 23 donors and the organ quality from post-euthanasia patients has been very good. Some tissues have been transplanted as well; however, concerns over transmission of neurological illness have limited tissue transplantation in some cases.

International policies on donation after medically-assisted death

While medically-assisted death is permitted in several countries now, donation is not possible in all these jurisdictions. See Table 3. In Switzerland, assisted suicide is legal but subsequent donation is not possible, in part, because the procedure is performed by non-physicians and does not occur in hospital. In Luxembourg, the law states that organs may only be procured after cessation of treatment due to extensive damage to the brain; therefore, conscious competent patients cannot consent to deceased donation.

Table 3: Policies on organ donation in countries where medically-assisted death is permitted (adapted from Allard and Fortin, J Med Ethics, 2017)

| Country or State | Policy on Organ Donation |

| Switzerland (assisted suicide by non-physician) | Not possible |

| Belgium (euthanasia) | Possible at patient request33 |

| Netherlands (euthanasia, assisted suicide) | Possible after euthanasia at patient’s request; working on an official post euthanasia donation protocol27 |

| Luxembourg (euthanasia) | Illegal |

| Oregon, Washington, Vermont, and Montana (assisted suicide) | Not possible |

| Ontario, Canada | Routine request |

| Quebec, Canada | Patient-initiated initially, currently routine request |

PDF copies of the full report is available by request. Submit a request by sending an email to OTDT@blood.ca, please include the title and use the subject line: PDF Document Request.

Acknowledgements

This report is dedicated to Dr. Shelly Sarwal and Dr. Linda Panaro who provided unique perspectives and thoughtful insights into the development of this expert guidance. Their knowledge and advocacy informed and guided the workshop process and has helped in the creation of this report which will guide practice and inform policy development both at the provincial and national level.

The planning committee would also like to acknowledge all individuals who contemplate organ donation as part of their end-of-life care after making the decision for medical assistance in dying or withdrawal of life-sustaining measures.

© Canadian Blood Services, 2018. All rights reserved.

Extracts from this report may be reviewed, reproduced or translated for educational purposes, research or private study, but not for sale or for use in conjunction with commercial purposes. Any use of this information should be accompanied by an acknowledgement of Canadian Blood Services as the source. Any other use of this publication is strictly prohibited without prior permission from Canadian Blood Services.

Canadian Blood Services assumes no responsibility or liability for any consequences, losses or injuries, foreseen or unforeseen, whatsoever or howsoever occurring, which might result from the implementation, use or misuse of any information or guidance in this report. This report contains guidance that must be assessed in the context of a full review of applicable medical, legal and ethical requirements in any individual case.

Production of this report has been made possible through financial contributions from Health Canada and the provincial and territorial governments. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of the federal, provincial or territorial governments.