Chapitre 18

Transfusion de plaquettes, l’allo-immunisation et la prise en charge de l’état réfractaire aux plaquettes

Contexte

D’un diamètre de 2 à 3 µm, les plaquettes sont les plus petites cellules sanguines1. Anucléées, elles ont pour principale fonction d’induire l’hémostase primaire, mais elles interviennent dans plusieurs autres processus, notamment l’immunité primaire, la progression des tumeurs et l’inflammation2. Les plaquettes circulent individuellement dans le flux sanguin jusqu’à ce qu’elles soient exposées à la matrice sous-endothéliale, par suite d’une lésion à un vaisseau sanguin. Elles s’activent alors et subissent des modifications morphologiques. Une fois activées, elles se lient aux parois lésées ainsi qu’à d’autres plaquettes pour former un clou hémostatique temporaire, ce qui amorce l’activation de facteurs de coagulation supplémentaires afin de former un clou hémostatique de fibrine plus permanent.

Le nombre de plaquettes varie normalement de 150 à 400 x 109/l. Les personnes dont la numération plaquettaire est très faible présentent un risque plus élevé d’hémorragie. Le risque d’hémorragie spontanée ou importante sur le plan clinique est plus grand quand la numération plaquettaire est inférieure à 10 x 109/l. Durant une chirurgie ou après une blessure, ce risque augmente quand la numération plaquettaire est inférieure à 30-50 x 109/l. Les personnes ayant des anomalies congénitales ou acquises de la fonction plaquettaire présentent aussi un risque plus élevé d’hémorragie.

La transfusion de plaquettes peut servir à augmenter le nombre de plaquettes fonctionnelles et donc à réduire les risques d’hémorragie. Le présent chapitre décrit le processus de prélèvement, de fabrication et de conservation des plaquettes destinées à la transfusion, contient les directives sur le processus transfusionnel et fournit des renseignements sur les réactions indésirables et l’état réfractaire à la transfusion de plaquettes.

Prélèvement, traitement et conservation des plaquettes destinées à la transfusion

Les concentrés plaquettaires sont prélevés et concentrés selon deux méthodes principales :

- Par extraction de la couche leucoplaquettaire : on prélève le sang total de différents donneurs, que l’on centrifuge ensuite pour séparer les plaquettes du plasma et des globules rouges (illustré au Chapitre 2, Les composants sanguins du présent Guide). Après la séparation, on mélange et met en suspension plusieurs unités de plaquettes de donneurs d’un même groupe sanguin, soit dans le plasma, soit dans une solution additive pour plaquettes (PAS). On emploie souvent les expressions « plaquettes mélangées » ou « pool de plaquettes » pour désigner ce type de concentré.

- Par aphérèse : les plaquettes d’un seul donneur sont prélevées à l’aide d’un appareil d’aphérèse. Cet appareil extrait le sang total du donneur, le centrifuge pour séparer les plaquettes et une petite quantité de plasma, puis retourne les autres composants sanguins dans le sang périphérique du donneur.

Il est à noter que les plaquettes prélevées selon l’une ou l’autre de ces méthodes peuvent encore être modifiées par le recours à une technologie d’inactivation des agents pathogènes (Chapitre 19, Plaquettes à teneur réduite en agents pathogènes dans le présent Guide), à la suspension dans une solution additive E pour plaquettes (PAS-E) plutôt que dans du plasma, au dépistage de titres anti-A et anti-B, et à l’étiquetage des composants à faible titre. Les mélanges plaquettaires sont désignés comme étant « anti-A/B faible » seulement lorsqu’il est confirmé que les niveaux anti-A et anti-B de toutes les unités prélevées du mélange sont inférieurs à un seuil prédéterminé (consultez notre FAQ : Test des titres d’iso-hémagglutinines (anti-A/anti-B) des donneurs à la Société canadienne du sang).

Un sommaire des caractéristiques des composants plaquettaires (c’est-à-dire volume unitaire moyen, nombre de donneurs dans une unité, volume plasmatique moyen, rendement plaquettaire approximatif, solution de resuspension, type d’anticoagulant, processus de dépistage bactérien et durée de conservation du composant) figure au tableau 2 du Chapitre 19 du présent Guide.

Les plaquettes obtenues par aphérèse et par extraction de la couche leucoplaquettaire sont déleucocytées et ont fait l’objet d’analyses bactériologiques (sauf si elles sont à teneur réduite en agents pathogènes; aucune analyse bactériologique n’est exigée pour ce type de plaquettes). Leur efficacité est jugée équivalente (Chapitre 2, Les composants sanguins dans le présent Guide). Il faut réserver les plaquettes d’aphérèse aux patients pour qui la présence d’alloanticorps dirigés contre l’antigène des leucocytes humains (anticorps anti-HLA) ou l’antigène de plaquettes humaines (anticorps anti-HPA) a été documentée, ainsi qu’aux patients réfractaires à la transfusion de plaquettes avec allo-immunisation, ou atteints d’un purpura post-transfusionnel ou d’une thrombocytopénie néonatale allo-immune.

Les unités de plaquettes doivent être conservées à température ambiante avec agitation. Elles ont une durée de conservation maximale de sept jours. Consultez le Chapitre 2, Les composants sanguins dans le présent Guide pour plus d’information sur la conservation des plaquettes.

Les protocoles et procédures de la Société canadienne du sang permettent de déterminer l’acceptabilité des unités plaquettaires pour leur distribution. Bien que la Société canadienne du sang ait adopté de stricts protocoles en vue de la fabrication des composants sanguins, ceux-ci peuvent être exposés à des conditions susceptibles de modifier leur apparence après leur fabrication (p. ex., pendant leur distribution ou leur stockage). En se fondant sur leurs politiques et procédures, les hôpitaux locaux déterminent si une unité plaquettaire est admissible ou non à la transfusion après sa distribution. L’Outil d’inspection visuelle est une ressource éducative qui renseigne l’utilisateur sur la variabilité visuelle des composants sanguins, de même que sur les causes à l’origine des changements. Il peut être utilisé conjointement avec les protocoles en place ou les directives de travail liées à l’inspection visuelle des composants sanguins. Pour une comparaison visuelle des types de plaquettes fabriquées par la Société canadienne du sang, consultez le Chapitre 19 du présent Guide. Pour obtenir des images supplémentaires d’unités de plaquettes accompagnées des conditions ou des caractéristiques susceptibles de modifier leur apparence visuelle, consultez l’Outil d’inspection visuelle.

Indications chez les patients adultes

Chez les personnes présentant une thrombocytopénie ou une dysfonction plaquettaire, la transfusion de plaquettes permet :

- d’arrêter les hémorragies (traitement thérapeutique);

- de prévenir les hémorragies (traitement prophylactique).

Chez un adulte pesant 70 kg, la transfusion d’une unité de plaquettes doit entraîner une augmentation de la numération plaquettaire de l’ordre de 15 à 25 x 109/l en moyenne3. Cette augmentation peut toutefois être supérieure ou inférieure selon la cause sous-jacente de la thrombocytopénie, la présence d’une ou de plusieurs maladies concomitantes et le poids du patient.

Transfusion thérapeutique de plaquettes

On dispose de peu de données scientifiques de qualité pour guider l’utilisation des transfusions de plaquettes dans le traitement des hémorragies. Toutefois, on reconnaît généralement que, dans un contexte d’hémorragie, les patients doivent recevoir des transfusions de plaquettes (Tableau 1).

Il est important de tenir compte de l’étiologie sous-jacente de la thrombocytopénie ou de la dysfonction plaquettaire, et du site de l’hémorragie. La thrombocytopénie peut survenir en raison d’une réduction de la production de plaquettes ou d’une augmentation de leur destruction, de leur consommation ou de leur séquestration. En cas de purpura thrombocytopénique thrombotique et de thrombocytopénie induite par l’héparine, on évite généralement les transfusions de plaquettes, car elles peuvent accroître le risque d’événements thrombotiques. En cas de purpura thrombocytopénique d’origine immunitaire, les transfusions de plaquettes sont généralement réservées aux hémorragies graves, car l’augmentation de la numération plaquettaire est atténuée chez les patients qui souffrent d’un tel trouble et, dans la plupart des cas, les risques associés aux transfusions de plaquettes peuvent l’emporter sur les avantages.

L’ajout d’agents hémostatiques doit être envisagé dans le cas d’une hémorragie active majeure. Les antifibrinolytiques, tels que l’acide tranexamique, sont particulièrement utiles dans le cas d’une hémorragie des muqueuses (p. ex. orale, gastro-intestinale, gynécologique). De plus, l’acide tranexamique a été associé à un meilleur taux de survie chez les patients qui souffrent d’une hémorragie liée à un traumatisme,4 d’une hémorragie post-partum5 ou d’un traumatisme crânien.6

La neutralisation d’anticoagulants spécifiques (p. ex. protamine pour l’héparine ou idarucizumab pour le dabigatran), ou encore le recours à des concentrés de complexe prothrombique (CCP) et à la vitamine K pour la neutralisation de la warfarine, sont utiles et doivent être envisagés.

L’efficacité et l’utilisation complémentaire de la desmopressine (DDAVP) sont de plus en plus remises en question. Bien que, dans les modèles animaux, la DDAVP puisse améliorer la fonction plaquettaire, il existe peu de preuves des avantages pour les patients atteints d’urémie (surtout avant une biopsie du rein7), les patients qui reçoivent des agents antiplaquettaires8 ou les patients en attente de chirurgie.9 La DDAVP peut se révéler efficace chez certains patients atteints de la maladie de von Willebrand (Chapitre 17, Troubles de l’hémostase et angiœdème héréditaire).10 Le recours à la DDAVP exige une surveillance étroite. De plus, l’équipe clinique doit composer avec les risques d’hyponatrémie, d’hypertension, de thrombose et de tachyphylaxie.

Tableau 1. Sommaire des recommandations relatives à la pratique clinique† pour les transfusions thérapeutiques de plaquettes chez les patients adultes souffrant d’une hémorragie

| Conditions cliniques | Recommandation |

|---|---|

| Hémorragies importantes | Une dose si la numération plaquettaire est inférieure à 50 x 109/L et vérification de la numération plaquettaire. |

| Traumatisme crânien ou hémorragie du système nerveux central | Une dose si la numération plaquettaire est inférieure 100 x 109/L et vérification la numération plaquettaire. |

| Dysfonction plaquettaire et hémorragies importantes (p. ex. bithérapie à l’acide acétylsalicylique et aux inhibiteurs de P2Y12) | Une dose, quelle que soit la numération plaquettaire pour traiter l’effet antiplaquettaire. |

| Traitement d’une hémorragie intracrânienne spontanée chez les patients traités à l’acide acétylsalicylique ou aux inhibiteurs de P2Y12 | Les transfusions de plaquettes ne sont pas recommandées. Les ouvrages actuels laissent entendre qu’elles ne comportent aucun avantage clinique et qu’elles peuvent être dangereuses pour les patients présentant une hémorragie intracrânienne spontanée et sous thérapie antiplaquettaire.11 |

| Dysfonction plaquettaire et hémorragie importante associées à un pontage cardiopulmonaire | Une dose, toutefois, la transfusion de plaquettes peut provoquer des effets indésirables et s’avérer inefficace. |

| Hémorragies chez les patients atteints d’une thrombocytopénie immune |

Consulter un hématologue. Une dose en cas d’hémorragie mettant en danger la vie du patient, mais uniquement si la numération plaquettaire est inférieure à 20 x 109/l. |

| Hémorragies chez les patients souffrant d’un traumatisme | Les transfusions de plaquettes doivent s’inscrire dans le cadre d’un protocole de transfusion massive. |

†Les recommandations relatives à la pratique clinique ont été formulées d’après un examen des lignes directrices reposant sur des données scientifiques, les listes des campagnes nationales Choosing Wisely et Choisir avec soin et des ouvrages actuels. Comme elles ne découlent pas d’une recherche documentaire officielle, ces pratiques sont fournies à titre de recommandations et non de lignes directrices.

Transfusion prophylactique de plaquettes

L’Association for Advancement of Blood and Biotherapies (AABB), le groupe International Collaboration for Transfusion Medicine Guidelines (ICTMG), l’American Association of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) et le British Committee for Standards in Hematology (BCSH) ont procédé à des examens systématiques distincts et utilisé les critères de méthodologie GRADE (Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation ou classement, évaluation et développement de recommandations) pour évaluer la qualité des données probantes relatives aux transfusions prophylactiques de plaquettes. Le guide de pratique clinique qui en a résulté12-16 renferme plusieurs recommandations relatives au recours à la transfusion de plaquettes pour prévenir les hémorragies.

Nous avons compilé les recommandations relatives à la pratique clinique pour les transfusions prophylactiques de plaquettes d’après un examen des lignes directrices reposant sur des données scientifiques, les listes des campagnes nationales Choosing Wisely et Choisir avec soin, les ouvrages actuels et l’avis des experts. Ces recommandations figurent au tableau 2.

Tableau 2. Sommaire des recommandations relatives à la pratique clinique pour les transfusions prophylactiques de plaquettes chez les patients adultes

| Conditions cliniques | Recommandation | Lignes directrices : |

|---|---|---|

|

Patients adultes hospitalisés qui souffrent de thrombocytopénie hypoproliférative liée au traitement (origine non immunitaire) |

Une dose si la numération plaquettaire est inférieure à |

Lignes directrices (2025) de l’AABB et l’ICTMG relatives à la pratique clinique,13 ASCO15 et BCSH14, et Choosing Wisely Canada |

| Insertion d’un cathéter veineux central dans des sites anatomiques favorables pour la compression manuelle | Une dose si la numération plaquettaire est inférieure à 10 x 109/l. |

Lignes directrices internationales (2025) de l’AABB et l’ICTMG relatives à la pratique clinique |

|

Ponction lombaire non urgente à but diagnostique Procédures de radiologie d’intervention à faible risque |

Une dose si la numération plaquettaire est inférieure à 20 x 109/l et vérification de la numération plaquettaire avant le début de la procédure. |

Lignes directrices internationales (2025) de l’AABB et l’ICTMG relatives à la pratique clinique,13 et lignes directrices du BCSH14 et de la Society of Interventional Radiology17 |

| Anticoagulation thérapeutique qui ne peut être interrompue |

Consulter un spécialiste des thromboses ou des hémostases. Une dose si la numération plaquettaire est inférieure à30 x 109/l. |

Avis d’experts |

| Patients atteints de leucémie promyélocytique aiguë (LPA) | Une dose si la numération plaquettaire est inférieure à 30-50 x 109/l. |

Recommandations du réseau European LeukemiaNet (2019)18 et du consensus canadien sur la LPA (2014)19 |

|

Chirurgie majeure non urgente non neuraxiale Procédures de radiologie d’intervention à risque élevé |

Une dose si la numération plaquettaire est inférieure à 50 x 109/l et vérification de la numération plaquettaire avant le début de la procédure. |

Lignes directrices internationales (2025) de l’AABB et l’ICTMG relatives à la pratique clinique,13 et lignes directrices de la Society of Interventional Radiology17 |

|

Chirurgie neuraxiale ou chirurgie impliquant le segment postérieur de l’œil |

Une dose si la numération plaquettaire est inférieure à |

Lignes directrices du BCSH14 et avis d’experts13 |

|

Procédure invasive chez les patients qui subissent un traitement antiplaquettaire (p. ex. ASA ou inhibiteurs de P2Y12) |

Aucune transfusion de plaquettes avant une procédure non urgente ne devrait avoir lieu si des agents antiplaquettaires sont toujours utilisés. Dans le cas des procédures invasives urgentes, la transfusion de plaquettes peut s’avérer efficace, mais elle doit être adaptée au patient selon son niveau particulier d’inhibition plaquettaire, et être réalisée en consultation avec des experts en médecine transfusionnelle. |

Lignes directrices du BCSH14 et avis d’experts |

Remarques :

- Ces recommandations relatives à la pratique clinique ont été formulées d’après un examen des lignes directrices reposant sur des données scientifiques, les listes des campagnes nationales Choosing Wisely et Choisir avec soin et des ouvrages actuels. Comme elles ne découlent pas d’une recherche documentaire officielle, ces pratiques sont fournies à titre de recommandations et non de lignes directrices.

- Association for Advancement of Blood and Biotherapies (AABB), International Collaboration for Transfusion Medicine Guidelines (ICTMG), American Association of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) et British Committee for Standards in Hematology (BCSH).

- Les lignes directrices du BCSH recommandent la transfusion prophylactique de plaquettes chez les patients qui souffrent de thrombocytopénie hypoproliférative réversible induite par la chimiothérapie intensive ou par une greffe allogénique de cellules souches hématopoïétiques (GACSH). Elles recommandent également de ne pas procéder à une transfusion prophylactique de plaquettes aux patients bien portants qui ont subi une GACSH autologue s’il n’y a aucune preuve d’hémorragie. De plus, les lignes directrices de l’ASCO suggèrent que, suivant une GACSH autologue, les patients adultes devraient recevoir une transfusion dans un centre spécialisé dès les premiers signes d’une hémorragie plutôt que prophylactiquement.

- Dans le cas de certaines procédures à très faible risque d’hémorragie (p. ex. ponction de la moelle osseuse ou biopsie par tréphine, cathéters centraux à insertion périphérique [CCIP], retrait par traction de cathéters veineux centraux tunnellisés ou chirurgie de la cataracte), les lignes directrices du BCSH recommandent de ne pas procéder automatiquement à une transfusion de plaquettes avant la procédure.

La recommandation en faveur de la transfusion pour les patients adultes hospitalisés qui souffrent de thrombocytopénie liée au traitement et dont la numération plaquettaire est inférieure à 10 x 109 cellules/l repose sur les résultats de plusieurs essais cliniques randomisés. Dans le cadre des deux essais les plus vastes,20, 21 on a comparé les résultats en matière d’hémorragie chez les patients qui avaient été traités au moyen de transfusions prophylactiques de plaquettes et ceux qui n’avaient reçu aucune transfusion plaquettaire. Les études ont montré que le recours à des transfusions prophylactiques de plaquettes réduisait les risques d’hémorragies importantes sur le plan clinique (niveau 2 ou supérieur). D’après les analyses des sous-groupes, certaines populations présentent des risques plus élevés d’hémorragie (p. ex. receveurs de greffes de cellules souches allogéniques) que d’autres (p. ex. receveurs de greffes de cellules souches autologues).20-23

Dans le cas des patients asymptomatiques non hospitalisés qui souffrent de thrombocytopénie hypoproliférative irréversible en raison d’une insuffisance médullaire chronique (p. ex. dans un contexte d’anémie aplasique ou de syndrome myélodysplasique) où aucun rétablissement n’est anticipé, une stratégie d’absence de transfusion prophylactique de plaquettes convient si ces patients ne subissent aucun traitement intensif ou aucune chimiothérapie par voie orale à faible dose.14, 15 Bien qu’il existe peu de preuves pour éclairer la pratique clinique, bon nombre de ces patients présentent peu ou pas d’hémorragies pendant de longues périodes, malgré une faible numération plaquettaire.

Seuils de transfusion de plaquettes :

Chez les patients ne présentant pas d’hémorragie ni de facteurs de risque d’hémorragie supplémentaires, la transfusion de plaquettes n’est indiquée que si la numération plaquettaire est égale ou inférieure à 10 x 109 cellules/l. Deux essais cliniques randomisés importants et une étude de cohortes prospective contrôlée ont montré que la réduction du seuil de transfusion prophylactique de 20 à 10 x 109 cellules/l diminuait l’utilisation de plaquettes de plus de 20 % sans pour autant accroître l’incidence d’hémorragies importants.24, 25 Il existe peu de données à l’appui de seuils précis de transfusion pour les patients présentant d’autres facteurs de risque hémorragique. Des seuils de transfusion prophylactique plus élevés (p. ex. 15 x 109 cellules/l) ont été utilisés dans le cas de patients présentant un plus grand risque d’hémorragie en raison d’une infection ou de l’utilisation d’anticoagulants, mais on ne dispose pas de données à l’appui de cette pratique.

Posologie : Au Canada, les composants plaquettaires fabriqués par la Société canadienne du sang ont un volume compris entre 264 et 273 ml pour les plaquettes non traitées (c’est-à-dire dont la teneur en agents pathogènes n’a pas été réduite) avec solution additive, et entre 170 et 281 x 109 pour les plaquettes à teneur réduite en agents pathogènes. Le contenu plaquettaire se situe entre 254 et 304 x 109 par unité dans le cas des plaquettes non traitées, et entre 210 et 276 x 109 par unité de plaquettes à teneur réduite en agents pathogènes. Ces chiffres proviennent des pages Web des circulaires d’information de la Société canadienne du sang relatives aux plaquettes. Veuillez les consulter pour prendre connaissance des volumes les plus récents. Veuillez également consulter le chapitre 19 pour obtenir plus d’information sur les plaquettes à teneur réduite en agents pathogènes.

En général, une poche de concentré plaquettaire augmente la numération plaquettaire d’environ 15 à 25 x 109/l chez un adulte de 70 kg. En pratique, après la transfusion, il est fréquent que la numération plaquettaire n’atteigne pas le niveau attendu. Une septicémie, une allo-immunisation, une fièvre, un purpura thrombocytopénique thrombotique ou une coagulation intravasculaire disséminée peut contribuer à une réaction sous-optimale. Même si les données disponibles révèlent une augmentation plus faible des plaquettes et des délais moins élevés entre les transfusions dans le cas des plaquettes à teneur réduite en agents pathogènes, les différences sont moindres.26

En cas de traitement prophylactique, des doses plus élevées entraînent une numération plaquettaire post-transfusionnelle supérieure et permettent de retarder la prochaine transfusion. Toutefois, selon des études récentes, notamment un vaste essai clinique randomisé, 27 le recours à des doses plus élevées ne réduit pas le risque d’hémorragie et fait augmenter la quantité totale de plaquettes utilisées chez les patients ayant besoin de transfusions à répétition. Par ailleurs, des doses plus faibles (équivalant à la moitié d’une unité plaquettaire standard provenant de donneurs multiples ou d’une unité standard de plaquettes d’aphérèse) se sont révélées aussi efficaces sur le plan clinique pour prévenir les hémorragies.27 Des transfusions plus fréquentes deviennent nécessaires, mais cette pratique réduit la quantité totale de plaquettes utilisées. C’est pourquoi, en cas de pénurie de plaquettes, le recours à la transfusion de doses divisées ou moins élevées de plaquettes peut constituer une stratégie utile pour gérer les problèmes d’approvisionnement.

Indications chez les patients néonatals et pédiatriques

Bien que plusieurs indications relatives à la transfusion de plaquettes chez les patients pédiatriques s’apparentent à celles de la transfusion de plaquettes chez l’adulte, leur physiologie est unique. Ils ne doivent pas être considérés comme de « petits adultes ». Chez ces patients, la transfusion doit être guidée par leur pathophysiologie sous-jacente, le risque d’hémorragie, leur âge, leur poids et la présence de comorbidités. Dans la mesure du possible, il est préférable de consulter un expert en transfusion pédiatrique.

Une discussion supplémentaire portant sur ce sujet figure au chapitre 13 du présent Guide.

Transfusion de plaquettes chez le nouveau-né

La transfusion de plaquettes se fait chez les nouveau-nés thrombocytopéniques. La thrombocytopénie est l’anomalie hématologique la plus courante chez les patients admis à l’unité des soins intensifs néonatals.28 Au cours des 90 premiers jours de vie, la numération plaquettaire normale pour un nourrisson né avant terme mais après 33 semaines d’âge gestationnel est de 123 à 450 x 109/l. Elle est de 104 à 450 x 109/l chez les nourrissons de moins de 32 semaines d’âge gestationnel.28

En général, il existe deux indications pour la transfusion de plaquettes chez les nouveau-nés thrombocytopéniques :

- prévention d’une hémorragie spontanée ou provoquée par la transfusion prophylactique de plaquettes au-delà d’un seuil critique;

- traitement d’une hémorragie active.

La majorité des transfusions de plaquettes chez les nouveau-nés sont de nature préventive. Chez les nouveau-nés thrombocytopéniques, les facteurs de risque d’hémorragie incluent les suivants :

- prématurité,

- poids faible ou très faible à la naissance,

- jumeaux ou grossesse multiple,

- diagnostic sous-jacent de thrombocytopénie fœtale et néonatale allo-immune (TFNAI),

- gravité de la thrombocytopénie.

Deux essais cliniques préalablement publiés appuient l’adoption d’une stratégie plus restrictive pour la transfusion de plaquettes. Elles recommandent un seuil inférieur à 25 x 109/l pour la transfusion prophylactique de plaquettes chez les nouveau-nés sans hémorragie. Le recours à des seuils plus élevés pour ce type de transfusion n’a pas permis de prouver qu’ils pouvaient prévenir les hémorragies intraventriculaires ni les autres types d’hémorragies. En fait, certaines preuves ont révélé une incidence accrue d’hémorragies importantes ou de décès à court terme.29, 30 Pour obtenir plus d’information sur l’administration de plaquettes chez les nouveau-nés, consultez le chapitre 13 du présent Guide.

Tableau 3. Seuils suggérés pour la transfusion de plaquettes chez les nouveau-nés qui souffrent de thrombocytopénie d’origine non immunitaire†.

| Conditions cliniques |

Seuil de numération plaquettaire (x109 par litre) |

|---|---|

| Aucune hémorragie | Moins de 25 |

| Nouveau-né avec une hémorragie, ou avant une chirurgie ou une procédure invasive | Moins de 50 |

| Nouveau-né avec une importante hémorragie (p. ex. hémorragie intracérébrale) ou ayant besoin d’une chirurgie neuraxiale | Moins de 100 |

†Ces recommandations relatives à la pratique clinique ont été formulées d’après un examen des ouvrages actuels et de lignes directrices publiées13, 31, 32 portant sur la transfusion de plaquettes chez les nouveau-nés. Comme elles ne découlent pas d’une recherche documentaire officielle, elles sont fournies à titre de recommandations et non de lignes directrices.

Les nouveau-nés qui souffrent de TFNAI ont été exclus des essais randomisés.

Les recommandations de l’International Collaboration for Transfusion Medicine Guidelines (ICTMG) relatives à la prise en charge postnatale de la TFNAI33 suggèrent un seuil initial de 100 x 109/l dans le cas des nouveau-nés atteints de TFNAI qui souffrent d’une hémorragie intracérébrale ou gastro-intestinale, puis un seuil de 50 x 109/l pendant sept jours. De plus, l’ICTMG recommande un seuil de 30 x 109/l dans le cas des nouveau-nés qui ne présentent aucun signe d’hémorragie menaçant la vie. Si elles sont disponibles, il est recommandé d’utiliser des plaquettes HPA compatibles. Sinon, il est préférable d’administrer des plaquettes HPA non spécifiques que de s’abstenir de procéder à une transfusion. Les plaquettes HPA compatibles peuvent être des plaquettes HPA spécifiques provenant de donneurs allogéniques compatibles ou encore des plaquettes maternelles. Pour prévenir toute réaction du greffon contre l’hôte (RGCH) associée à la transfusion, les plaquettes maternelles doivent être irradiées ou traitées au psoralène afin d’assurer l’absence de lymphocytes résiduels viables. Consultez le chapitre 12 du présent Guide pour obtenir plus d’information sur les tests sérologiques et la prise en charge des grossesses subséquentes chez les femmes qui ont déjà donné naissance à un enfant atteint de TFNAI.

Transfusion de plaquettes chez l’enfant

Les lignes directrices relatives à la transfusion de plaquettes chez l’enfant sont semblables à celles qui s’appliquent aux adultes (les doses recommandées pour la transfusion pédiatrique et néonatale de plaquettes figurent dans la Circulaire d’information de la Société canadienne du sang), même si les enfants sont sous-représentés dans les essais cliniques axés sur le traitement prophylactique des patients hospitalisés souffrant de thrombocytopénie. La décision d’administrer des plaquettes aux enfants doit tenir compte de l’étiologie et de l’histoire naturelle prévue de la thrombocytopénie. Chez les enfants atteints d’un purpura thrombocytopénique d’origine immunitaire, comme chez les adultes, la transfusion de plaquettes ne doit être envisagée qu’en cas d’hémorragie importante.

Sélection des plaquettes

Les plaquettes expriment les antigènes A et B sur leur membrane, mais non les antigènes Rh. Idéalement, le groupe ABO des plaquettes transfusées doit être identique à celui du receveur, mais des plaquettes d’un groupe ABO différent peuvent être transfusées si on ne peut obtenir des plaquettes ABO compatibles. Selon certaines données scientifiques, les plaquettes ABO incompatibles constituent un facteur de risque de faible augmentation de la numération plaquettaire après une transfusion. Les risques associés à la transfusion de plaquettes incompatibles sont présentés à la Figure 1.

Certaines études semblent indiquer que les plaquettes ABO incompatibles constituent un facteur de risque pour de faibles augmentations de la numération plaquettaire.34 Toutefois, l’importance sur le plan clinique est limitée. Dans une analyse secondaire de l’étude PLADO, la transfusion de plaquettes ABO identiques et plus fraîches avait accru modestement la numération plaquettaire après la transfusion (par rapport aux plaquettes provenant de sang total, non identiques ou plus vieilles), mais il n’existe aucune incidence mesurable sur la prévention de l’hémorragie sur le plan clinique.3, 27

Des cas d’hémolyse attribuables à la présence d’anticorps anti-A et anti-B (aussi appelés iso-hémagglutinines) dans le plasma d’unités de plaquettes ABO incompatibles ont déjà été signalés. La concentration d’iso-hémagglutinines est plus faible dans les concentrés plaquettaires traités au psoralène et suspendus dans une PAS-E. On considère que la réduction de la concentration plasmatique des unités plaquettaires réduit l’exposition globale à ces anticorps. Certains services de transfusion déterminent d’emblée le titre d’anticorps anti-A et anti-B dans les plaquettes du groupe O (surnageant) et évitent d’utiliser des unités du groupe O chez les patients d’autres groupes sanguins quand le titre est supérieur à un seuil prédéterminé. La Société canadienne du sang détermine le titre d’anticorps anti-A et anti-B de chaque don de sang total et de plaquettes d’aphérèse. Si les titres sont inférieurs au seuil prédéterminé chez tous les donneurs contribuant à un mélange de plaquettes, ou chez un donneur de plaquettes d’aphérèse, le composant correspondant est étiqueté « Low Anti-A/B » (anti A/B faible). Pour plus de précisions, consultez la FAQ : Test des titres d’iso-hémagglutinines (anti-A/anti-B) des donneurs à la Société canadienne du sang.

Bien que les plaquettes n’expriment pas d’antigènes Rh, les produits plaquettaires peuvent contenir de faibles quantités de globules rouges. La transfusion de plaquettes de donneurs Rh positif à des receveurs Rh négatif peut donc entraîner la production d’anticorps dirigés contre l’antigène RhD par le receveur, ce qui pourrait nuire aux transfusions ultérieures ou compliquer les grossesses. Dans ces cas, l’administration d’immunoglobulines anti-D (WinRho) peut être envisagée chez les jeunes filles et les femmes Rh négatif en âge de procréer dans les 72 heures suivant la transfusion de plaquettes provenant d’un donneur Rh positif.35, 36 Des données scientifiques semblent indiquer un faible taux d’allo-immunisation chez les receveurs de transfusions de plaquettes RhD incompatibles sans immunoglobulines anti-D dans la population générale.37 Des facteurs cliniques, tels qu’une chimiothérapie ou une immunosuppression récente, peuvent réduire le taux d’allo-immunisation et influer sur la décision d’administrer des immunoglobulines anti-D. Les plaquettes d’aphérèse fabriquées au moyen des protocoles actuels présentent une contamination minimale des globules rouges38 et, par conséquent, le taux d’allo-immunisation après des transfusions de plaquettes d’aphérèse RhD incompatibles est extrêmement faible.39, 40

Les plaquettes comportent des antigènes HLA de classe I et des antigènes qui leur sont propres, c’est-à-dire les HPA. L’allo-immunisation anti-HLA ou anti-HPA est l’une des causes de l’état réfractaire à la transfusion de plaquettes. Veuillez consulter la section portant sur ce sujet.

Réactions indésirables

La transfusion de plaquettes est associée à des effets indésirables infectieux ou non (tableau 4). Se reporter au chapitre 10 du présent Guide et à l’information sur le signalement des réactions transfusionnelles indésirables fournie par la Société canadienne du sang.

Infection bactérienne

Le risque de transmission d’infections virales pour une unité de plaquettes est le même que pour une unité de globules rouges. Toutefois, le risque d’infection bactérienne suscite davantage d’inquiétudes dans le cas des plaquettes en raison de leur conservation à la température ambiante.

La source des infections bactériennes est habituellement due à la présence d’une bactérie à la surface de la peau du donneur qui aurait été acquise pendant le prélèvement ou, plus rare, à une bactériémie chez le donneur. Une combinaison de stratégies permet d’identifier et de réduire le risque d’infection bactérienne des composants plaquettaires. Ces stratégies incluent la déviation des premiers 10 ml du produit prélevé pour éliminer la prise percutanée, l’analyse bactérienne systématique de tous les composants non pathogènes inactivés, ainsi que l’introduction de concentrés plaquettaires aux agents pathogènes inactivés traités au psoralène. Pour obtenir plus d’information sur l’analyse bactériologique des plaquettes, veuillez consulter la FAQ sur le dépistage bactériologique des plaquettes à la Société canadienne du sang. Vous pouvez également consulter le chapitre 19 du présent Guide pour vous renseigner davantage sur les plaquettes à teneur réduite en agents pathogènes. Les taux annuels d’infection bactérienne figurent également dans le Rapport de surveillance de la Société canadienne du sang.

État réfractaire à la transfusion de plaquettes avec allo-immunisation

La transfusion de plaquettes est associée à une complication unique en son genre : l’état réfractaire à la transfusion de plaquettes avec allo-immunisation. Quand ce problème survient, la transfusion régulière de plaquettes ne permet plus d’augmenter la numération plaquettaire du patient, car son système immunitaire les détruit immédiatement. Cette complication se produit chez les patients qui possèdent des anticorps anti-HLA ou qui développent des anticorps antiplaquettaires après une transfusion sanguine ou une grossesse. Les risques de développer un état réfractaire à la transfusion de plaquettes ont été grandement réduits (à environ 4 % des receveurs) par l’introduction de la réduction leucocytaire systématique de tous les composants sanguins cellulaires.41 Les risques d’allo-immunisation et de développement d’un état réfractaire contre les plaquettes issues de sang total et les plaquettes d’aphérèse sont similaires, car les deux produits font l’objet d’une réduction leucocytaire. Seule la transfusion d’unités de plaquettes d’aphérèse sélectionnées expressément par typage HLA ou HPA négatif peut accroître adéquatement la numération plaquettaire chez ces patients (voir ci-après « État réfractaire à la transfusion de plaquettes »).

Réaction du greffon contre l’hôte (RGCH associée à la transfusion)

Bien que les transfusions de plaquettes d’aphérèse puissent réduire l’exposition à différents donneurs, les plaquettes d’aphérèse provenant d’un donneur aux plaquettes HLA compatibles ou d’un parent par le sang peuvent augmenter le risque de RGCH. Pour prévenir cette complication rare, tous les composants HLA compatibles doivent être irradiés pour détruire les lymphocytes résiduels, sauf s’il s’agit de plaquettes à teneur réduite en agents pathogènes (veuillez consulter les Recommandations sur l’utilisation de produits sanguins irradiés au Canada du Comité consultatif national sur le sang et les produits sanguins).

Tableau 4. Réactions indésirables à la suite d’une transfusion de plaquettes42-46

Source : Tableau adapté de la Circulaire d’information de la Société canadienne du sang (2024)47

|

Réaction |

Fréquence approximative |

Symptômes et signes |

Remarques |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Légère réaction allergique |

1 cas sur 100 |

Urticaire, prurit ou érythème |

La transfusion peut être reprise après avoir évalué la réaction et pris les mesures nécessaires. |

|

Réactions transfusionnelles fébriles non hémolytiques |

De 0,5 à 2 cas sur 100 |

Fièvre, frissons et frissons solennels |

Diagnostic par élimination. Il convient de déterminer si les patients ayant de la fièvre ont d’autres réactions transfusionnelles plus graves. |

|

Surcharge circulatoire post-transfusionnelle |

De 0,1 à 1 cas sur 100 |

Dyspnée, orthopnée, cyanose, tachycardie, tension veineuse élevée et hypertension |

Réaction due à un volume excessif ou à un débit de transfusion trop rapide. Il peut être difficile de la distinguer du TRALI. |

|

Réaction septique |

Rare |

Fièvre, frissons, frissons solennels, nausée, vomissements, diarrhée, douleurs abdominales et musculaires, hypotension, hémoglobinémie, coagulation intravasculaire disséminée et insuffisance rénale |

Fréquence approximative pour chaque transfusion de concentré de plaquettes selon les données de la Société canadienne du sang* :

Comme l’ont indiqué d’autres organismes internationaux d’approvisionnement en sang :

|

|

Syndrome respiratoire aigu post-transfusionnel (TRALI) |

De 0,5 à 1 cas sur 100 000 |

Nouvel épisode d’hypoxémie et nouveaux infiltrats pulmonaires bilatéraux visibles à la radiographie pulmonaire, mais aucun signe de surcharge circulatoire |

Réaction survenant pendant la transfusion ou dans les six heures suivantes. Il peut être difficile de la distinguer de la surcharge circulatoire. |

|

Purpura post-transfusionnel (PPT) |

Très rare |

Survenue soudaine d’une thrombocytopénie grave dans les 24 jours suivant la transfusion |

La PPT survient le plus souvent chez les patients homozygotes pour l’antigène HPA-1b, qui reçoivent des composants sanguins positifs HPA-1a. |

|

Thrombocytopénie allo-immune transfusionnelle |

Rare |

Survenue soudaine d’une thrombocytopénie grave dans les heures suivant la transfusion |

Transfert passif d’anticorps plaquettaires, qui entraîne une thrombocytopénie. |

|

Réactions hémolytiques transfusionnelles immédiates |

Rare |

Fièvre, frissons, hémoglobinurie, dyspnée, état de choc, coagulation intravasculaire disséminée, douleurs thoraciques et dorsales |

Réactions pouvant être liées à une incompatibilité ABO. |

|

Anaphylaxie |

Rare |

Hypotension, obstruction des voies respiratoires inférieures ou supérieures, anxiété, nausée et vomissements |

Réanimation selon les lignes directrices de l’établissement. Les sujets ayant un déficit en IgA et des anticorps anti-IgA risquent de faire une réaction anaphylactique. On ne décèle cependant pas d’anticorps |

|

Réaction du greffon contre l’hôte (RGCH) |

Très rare |

Pancytopénie, éruption cutanée, trouble hépatique et diarrhée |

Les composants sanguins cellulaires irradiés permettent d’éliminer ce risque. |

|

Réaction hypotensive isolée |

Inconnue |

Hypotension parfois accompagnée d’urticaire, de dyspnée et de nausée |

Diagnostic par élimination. Cette réaction peut être plus fréquente chez les patients |

|

Maladie infectieuse |

Pour les risques résiduels d’infections virales, voir le Rapport de surveillance. |

Signes et symptômes variant selon la maladie infectieuse. |

Les composants sanguins sont susceptibles de transmettre des virus autres que le VIH, le VHB, le VHC, le HTLV-1, le HTLV‑2 et le VNO ainsi que des parasites et des prions. |

Situations particulières

État réfractaire à la transfusion de plaquettes

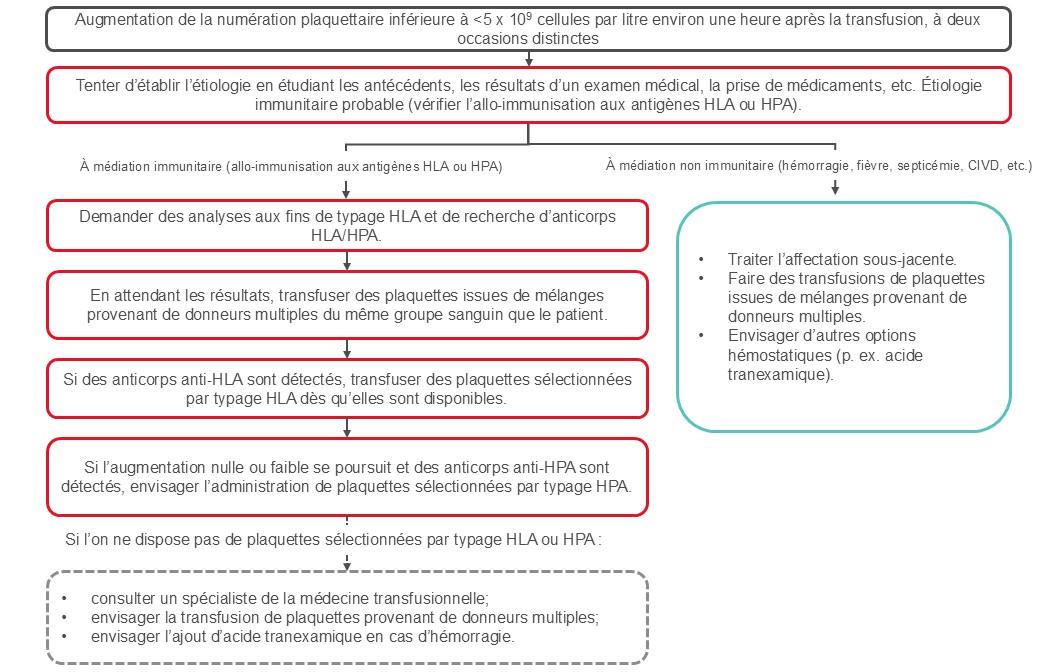

L’état réfractaire à la transfusion de plaquettes est une complication importante chez les patients atteints de thrombopénie. Il peut s’agir d’un état à médiation immunitaire (20 % des patients) ou non (80 % des patients). La Figure 2 présente un algorithme relatif à la prise en charge de l’état réfractaire à la transfusion de plaquettes.

Ses causes non immunitaires comprennent la fièvre, une infection, la prise de certains médicaments, une splénomégalie ou une coagulation intravasculaire disséminée. L’obtention des antécédents médicaux détaillés du patient et la réalisation d’un examen médical aident à déterminer la cause de la complication et à définir les objectifs ainsi que l’urgence du traitement.

Chez les patients répondant mal à la transfusion de plaquettes, la vérification de la numération plaquettaire post-transfusionnelle environ une heure après la transfusion peut aider à déterminer s’il s’agit d’un état réfractaire d’origine immune ou non. Des études à ce sujet ont utilisé divers calculs48 pour définir l’état réfractaire à la transfusion de plaquettes (encadré 1).

| Encadré 1. Divers calculs utilisés pour définir l’état réfractaire à la transfusion de plaquettes |

|---|

|

Augmentation de la numération plaquettaire (PI) = P2-P1, où P1 est la numération plaquettaire prétransfusionnelle et P2 est la numération plaquettaire post-transfusionnelle. Corrected Count Increment (CCI) = [(PI x SC)/n] x 100, où SC représente la surface corporelle en mètres carrés et n, le nombre de plaquettes transfusées. Rendement transfusionnel plaquettaire (RTP) = [(PI x poids corporel (kg) x 0,075 (l/kg))/n] x 100. Le poids corporel (kg) x 0,075 (l/kg) est une estimation du volume sanguin. |

Chez les patients répondant mal à la transfusion de plaquettes, on peut établir l’efficacité d’une transfusion en effectuant des mesures entre 10 et 60 minutes après la transfusion pour déterminer si l’allo-immunisation est la cause probable de l’état réfractaire. Une CCI inférieure à 7,5 x 109/l ou un RTP inférieur à 30 % une heure après la transfusion permet de croire à la présence d’un état réfractaire avec allo-immunisation. Une bonne augmentation après une heure suivie d’une diminution inférieure à 7,5 x 109 cellules par litre après 24 heures semble indiquer une destruction non immunologique des plaquettes. Il est à noter que certaines institutions utilisent une augmentation corrigée entre 5 et 7,5 x 109/l. Il est possible d’utiliser un seuil d’augmentation corrigée inférieur si le patient souffre de plusieurs comorbidités pouvant expliquer une augmentation plaquettaire inférieure, en plus des anticorps anti-HLA ou anti-HPA.

Puisqu’on ne mesure pas systématiquement la numération plaquettaire des unités de plaquettes, une augmentation de la numération inférieure à 5 à 10 x 109cellules/l une heure après la transfusion peut être utilisée au lieu de la CCI ou du RTP.

La recherche d’anticorps HLA ou HPA peut être effectuée à l’aide d’analyses spéciales, notamment à l’aide d’un test de dépistage des anticorps lymphocytotoxiques et de la cytométrie de flux. Le laboratoire national de référence d’immunologie plaquettaire de la Société canadienne du sang (en anglais) offre ce type d’analyse pour les receveurs. L’allo-immunisation HLA est plus souvent en cause que l’allo-immunisation HPA dans le développement d’un état réfractaire à la transfusion de plaquettes.

L’état réfractaire à la transfusion de plaquettes ne s’accompagne pas toujours d’une allo-immunisation. La prise en charge d’un état réfractaire d’origine immune est différente de celle d’un état réfractaire d’origine non immune (Figure 2). Une fois que les anticorps anti-HLA ou anti-HPA antiplaquettaires ont été identifiés, la transfusion de plaquettes d’aphérèse compatibles peut permettre d’obtenir une augmentation adéquate de la numération plaquettaire. À la Société canadienne du sang, des produits plaquettaires sélectionnés par typage HLA ou HPA peuvent être obtenus auprès de donneurs de plaquettes par aphérèse phénotypés. La recherche de donneurs compatibles peut prendre du temps et il est possible que les donneurs ne soient pas disponibles immédiatement. C’est pourquoi il y a souvent un délai de plusieurs jours avant la réception du produit plaquettaire initial sélectionné par typage HLA ou HPA.

Après examen systématique du rendement de la transfusion de plaquettes HLA compatibles chez des patients atteints de thrombocytopénie hypoproliférative, il apparaît que celles-ci ne réduisent pas plus le taux d’allo-immunisation ou d’état réfractaire que la réduction leucocytaire.16 La transfusion de plaquettes HLA compatibles a engendré une plus grande augmentation de la numération plaquettaire après une heure et à un pourcentage plus élevé de récupération plaquettaire chez les patients réfractaires. Toutefois, après 24 heures, le rendement n’était pas uniforme.16 En outre, la transfusion de plaquettes d’aphérèse sélectionnées par typage HLA ou HPA ne présente aucun avantage pour les patients chez qui la présence d’anticorps anti-HLA ou anti-HPA n’est pas démontrée. Les essais cliniques prospectifs rigoureux d’une puissance statistique adéquate ne sont pas suffisants pour appuyer les pratiques actuelles axées sur la compatibilité HLA. Il faudrait mener des études prospectives multicentres comparant des approches qui visent à déceler les différences dans les résultats importants chez les patients et les répercussions sur les ressources.49

En pratique, certaines lignes directrices courantes sont appliquées au moment de déterminer si un patient doit recevoir des plaquettes sélectionnées par typage HLA. Si des anticorps anti-HLA sont détectés, un calculateur du PRA cumulatif (cPRA) est couramment utilisé pour déterminer dans quels cas il faut commander des plaquettes sélectionnées par typage HLA. Le cPRA estime le pourcentage de la population qui est incompatible avec le patient. Par exemple, un cPRA de 80 % permet de prédire que 80 % des plaquettes prélevées seraient incompatibles et n’augmenteraient pas adéquatement la numération plaquettaire après la transfusion. La plupart du temps, un patient ayant un cPRA inférieur à 30 % est inadmissible aux plaquettes sélectionnées par typage HLA, car au moins un des donneurs du bassin doit être compatible avec lui.

Dans le cas des patients ayant un cPRA supérieur à 95 % ou des patients ayant un cPRA élevé et un besoin soutenu en matière de soutien transfusionnel (p. ex. cPRA de plus de 80 %), il peut être difficile de trouver des plaquettes compatibles dans des délais convenables. Il est possible de sélectionner des plaquettes incompatibles permissives, au cas par cas. Un faible taux d’anticorps positifs anti-HLA permet des augmentations de la numération plaquettaire équivalentes à celles des plaquettes HLA entièrement compatibles, ainsi que l’augmentation du bassin de donneurs compatibles pour appuyer les besoins d’un patient en matière de transfusion.50, 51

Le groupe The International Collaboration for Transfusion Medicine Guidelines (ICTMG) a formulé des recommandations concernant la prise en charge des patients atteints de thrombocytopénie hypoproliférative réfractaires à la transfusion de plaquettes. Elles sont présentées au Tableau 5.35

Tableau 5. Recommandations du groupe International Collaboration for Transfusion Medicine Guidelines relatives à la prise en charge des patients atteints de thrombocytopénie hypoproliférative qui sont réfractaires aux transfusions de plaquettes.35

| Conditions cliniques | Recommandation relative à la transfusion de plaquettes | Niveau de preuve |

|---|---|---|

| Anticorps anti-HLA de classe I | Le patient devrait probablement recevoir une transfusion de plaquettes typées HLA de classe I ou sélectionnées dans un groupe de donneurs. | Faible |

| Anticorps anti-HPA | Le patient devrait probablement recevoir une transfusion de plaquettes sélectionnées par typage HPA ou sélectionnées dans un groupe de donneurs. | Très faible |

| Origine non immunitaire (p. ex. aucun anticorps anti-HLA de classe I ou anti-HPA) | Le patient ne devrait probablement pas recevoir de transfusion de plaquettes sélectionnées par typage HPA ou sélectionnées dans un groupe de donneurs. | Très faible |

Figure 2. Prise en charge de l’état réfractaire à la transfusion de plaquettes. L’algorithme tient compte des lignes directrices publiées par l’ICTMG. 35

La prise en charge des patients allo-immunisés réfractaires à la transfusion de plaquettes et ne répondant pas à l’administration de plaquettes compatibles pose problème. Malgré leurs résultats médiocres sur le plan de l’augmentation de la numération plaquettaire, la transfusion régulière de plaquettes peut tout de même présenter des avantages d’ordre hémostatique pour ces patients.

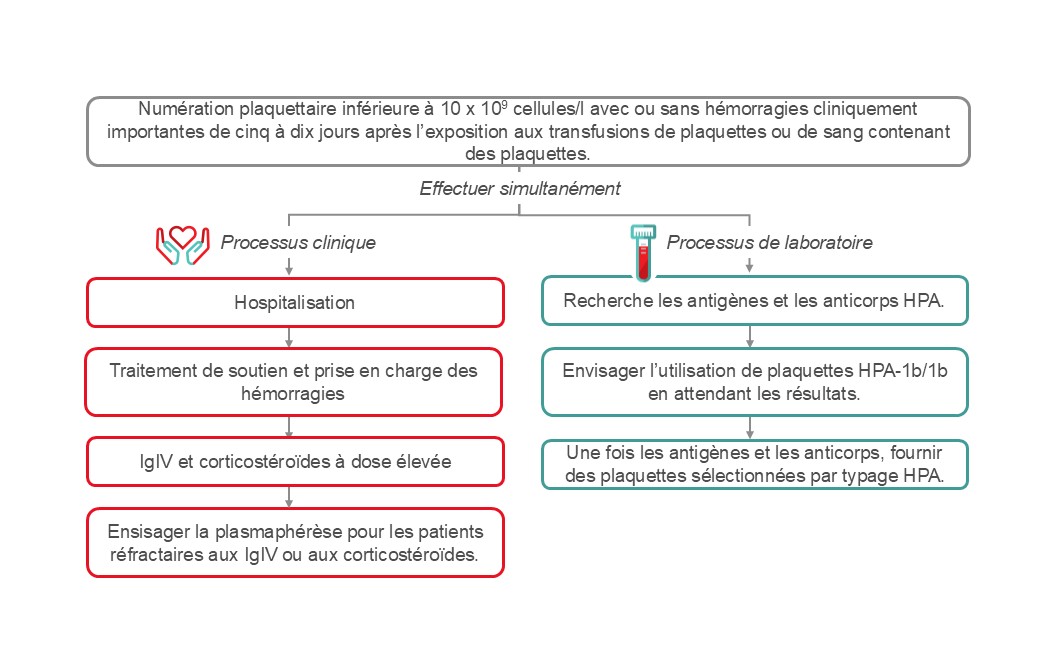

Purpura post-transfusionnel

Le purpura post-transfusionnel est un syndrome thrombocytopénique rare dont l’incidence se situe entre 1 et 2 pour 100 000 transfusions plaquettaires.52, 53 Il peut représenter 0,04 % de toutes les réactions indésirables signalées.54 La transfusion de plaquettes est l’élément déclencheur le plus souvent cité, mais le purpura post-transfusionnel peut également survenir après une transfusion de globules rouges. Son incidence a été ramenée de 10,3 cas par an, entre 1996 et 1999, à 2,3 cas par an, entre 2000 et 2005, après la mise en œuvre de la réduction leucocytaire en 1999.52

Le purpura post-transfusionnel est une réaction à médiation immunitaire dirigée contre les antigènes HPA – le plus souvent les antigènes HPA-1a. Il survient le plus souvent chez les patients homozygotes pour l’antigène HPA-1b, qui ne possèdent pas l’antigène plaquettaire HPA-1a courant. Un événement, tel qu’une grossesse ou une transfusion, peut provoquer le développement d’anticorps anti-HPA-1a. Ces anticorps détruisent non seulement les plaquettes HPA incompatibles, mais également les plaquettes du patient, ce qui entraîne une grave thrombocytopénie. Des auto-anticorps dirigés vers les antigènes plaquettaires du receveur et des anticorps dirigés vers d’autres antigènes plaquettaires ont également été décrits.55-58

Le purpura post-transfusionnel se présente sous la forme d’une thrombocytopénie profonde (numération plaquettaire inférieure à 10 x 109 cellules/l) entre cinq et dix jours après une transfusion. La thrombocytopénie peut se résorber dans un délai d’une semaine ou deux, mais elle peut également durer plus longtemps. Un purpura post-transfusionnel entraîne un risque d’hémorragie importante sur le plan clinique. Selon les estimations, le taux de mortalité se situerait entre 5 et 20 %. La majorité des épisodes se produisent chez les femmes ayant eu une grossesse, mais il peut aussi survenir chez les hommes.

Le diagnostic de purpura post-transfusionnel peut se confirmer par la détection d’anticorps spécifiques de plaquettes et par le typage HPA. Il est essentiel d’exclure tout autre trouble thrombocytopénique grave, tel que la coagulopathie intravasculaire disséminée, le purpura thrombocytopénique auto-immun, la thrombocytopénie induite par l’héparine, le purpura thrombocytopénique thrombotique et la thrombocytopénie destructrice.

L’algorithme pour la gestion du purpura post-transfusionnel est présenté à la figure 3. Il est important d’exclure d’autres causes possibles de thrombocytopénie grave chez ces patients. Le traitement vise à atténuer le risque d’hémorragie et il faut souvent recourir à une thérapie multimodale émergente selon la gravité. Le traitement doit être administré sans attendre les résultats des études sérologiques. Les principaux éléments de la thérapie incluent une dose élevée d’immunoglobuline intraveineuse (IgIV), les corticostéroïdes et, en cas d’hémorragie, la transfusion de plaquettes HPA compatibles. L’échange de plasma (recommandation 2B) constitue une autre option de traitement.59

Crédits de développement professionnel continu

Les associés et les professionnels de la santé qui participent au Programme de maintien du certificat du Collège royal des médecins et chirurgiens du Canada peuvent demander que la lecture du Guide de la pratique transfusionnelle soit reconnue comme activité de développement professionnel continu au titre de la Section 2 – Apprentissage individuel. Ces personnes peuvent réclamer 0,5 crédit par heure de lecture, jusqu’à hauteur de 30 crédits par année.

Les technologistes médicaux qui participent au Programme d’enrichissement professionnel (PEP) de la Société canadienne de science de laboratoire médical peuvent demander que la lecture du Guide de la pratique transfusionnelle soit reconnue en tant qu’activité non vérifiée.

Remerciements

Les auteurs remercient Tanya Petraszko, MD, FRCPC, et Michelle Zeller, MD, FRCPC, MHPE, DRCPSC, auteures de la version précédente du présent chapitre, ainsi que le Dr Andrew Shih et la Dre Caroline Malcolmson, qui ont passé en revue le présent chapitre.

Si vous avez des questions ou des suggestions d’amélioration concernant le Guide de la pratique transfusionnelle, veuillez communiquer avec nous par l’entremise de notre formulaire.

Suggestion de citation

Lafrance, C., Malcolmson, C., Ning, S., Anani W., Yan, M. Transfusion de plaquettes, allo-immunisation et prise en charge de l’état réfractaire aux plaquettes. In: Khandelwal A, Brooks K., éditeurs. Guide de la pratique transfusionnelle [Internet]. Ottawa : Société canadienne du sang, 2025 [cité AAAA MM JJ]. Chapitre 18. Lien : Bienvenue | Développement professionnel.

Si vous avez des questions ou des suggestions d’amélioration concernant le Guide de la pratique transfusionnelle, veuillez communiquer avec nous par l’entremise de notre formulaire.

Références

- Patel, S. R., Hartwig, J. H., & Italiano, J. E., Jr. (2005). The biogenesis of platelets from megakaryocyte proplatelets. J Clin Invest, 115(12), 3348-3354. https://doi.org/10.1172/jci26891

- Brass, L. (2010). Understanding and evaluating platelet function. Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program, 2010, 387-396. https://doi.org/10.1182/asheducation-2010.1.387

- Triulzi, D. J., Assmann, S. F., Strauss, R. G., Ness, P. M., Hess, J. R., Kaufman, R. M., Granger, S., & Slichter, S. J. (2012). The impact of platelet transfusion characteristics on posttransfusion platelet increments and clinical bleeding in patients with hypoproliferative thrombocytopenia. Blood, 119(23), 5553-5562. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2011-11-393165

- Roberts, I., Shakur, H., Coats, T., Hunt, B., Balogun, E., Barnetson, L., Cook, L., Kawahara, T., Perel, P., Prieto-Merino, D., Ramos, M., Cairns, J., & Guerriero, C. (2013). The CRASH-2 trial: a randomised controlled trial and economic evaluation of the effects of tranexamic acid on death, vascular occlusive events and transfusion requirement in bleeding trauma patients. Health Technol Assess, 17(10), 1-79. https://doi.org/10.3310/hta17100

- WOMAN Trial Collaborators. (2017). Effect of early tranexamic acid administration on mortality, hysterectomy, and other morbidities in women with post-partum haemorrhage (WOMAN): an international, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet, 389(10084), 2105-2116. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(17)30638-4

- Crash-3 trial collaborators. (2019). Effects of tranexamic acid on death, disability, vascular occlusive events and other morbidities in patients with acute traumatic brain injury (CRASH-3): a randomised, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet (London, England), 394(10210), 1713-1723. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(19)32233-0

- Leclerc, S., Nadeau-Fredette, A. C., Elftouh, N., Lafrance, J. P., Pichette, V., & Laurin, L. P. (2020). Use of Desmopressin Prior to Kidney Biopsy in Patients With High Bleeding Risk. Kidney Int Rep, 5(8), 1180-1187. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ekir.2020.05.006

- Desborough, M. J., Oakland, K. A., Landoni, G., Crivellari, M., Doree, C., Estcourt, L. J., & Stanworth, S. J. (2017). Desmopressin for treatment of platelet dysfunction and reversal of antiplatelet agents: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Thromb Haemost, 15(2), 263-272. https://doi.org/10.1111/jth.13576

- Andersen, L. K., Hvas, A. M., & Hvas, C. L. (2021). Effect of Desmopressin on Platelet Dysfunction During Antiplatelet Therapy: A Systematic Review. Neurocrit Care, 34(3), 1026-1046. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12028-020-01055-6

- Mohinani, A., Patel, S., Tan, V., Kartika, T., Olson, S., DeLoughery, T. G., & Shatzel, J. (2023). Desmopressin as a hemostatic and blood sparing agent in bleeding disorders. Eur J Haematol, 110(5), 470-479. https://doi.org/10.1111/ejh.13930

- Baharoglu, M. I., Cordonnier, C., Al-Shahi Salman, R., de Gans, K., Koopman, M. M., Brand, A., Majoie, C. B., Beenen, L. F., Marquering, H. A., Vermeulen, M., Nederkoorn, P. J., de Haan, R. J., & Roos, Y. B. (2016). Platelet transfusion versus standard care after acute stroke due to spontaneous cerebral haemorrhage associated with antiplatelet therapy (PATCH): a randomised, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet, 387(10038), 2605-2613. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(16)30392-0

- Kaufman, R. M., Djulbegovic, B., Gernsheimer, T., Kleinman, S., Tinmouth, A. T., Capocelli, K. E., Cipolle, M. D., Cohn, C. S., Fung, M. K., Grossman, B. J., Mintz, P. D., O'Malley, B. A., Sesok-Pizzini, D. A., Shander, A., Stack, G. E., Webert, K. E., Weinstein, R., Welch, B. G., Whitman, G. J., . . . AABB. (2015). Platelet transfusion: a clinical practice guideline from the AABB. Ann Intern Med, 162(3), 205-213. https://doi.org/10.7326/M14-1589

- Metcalf, R. A., Nahirniak, S., Guyatt, G., Bathla, A., White, S. K., Al-Riyami, A. Z., Jug, R. C., La Rocca, U., Callum, J. L., Cohn, C. S., DeAnda, A., DeSimone, R. A., Dubon, A., Estcourt, L. J., Filipescu, D. C., Fung, M. K., Goel, R., Hess, A. S., Hume, H. A., . . . Stanworth, S. J. (2025). Platelet Transfusion: 2025 AABB and ICTMG International Clinical Practice Guidelines. JAMA. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2025.7529

- Estcourt, L. J., Birchall, J., Allard, S., Bassey, S. J., Hersey, P., Kerr, J. P., Mumford, A. D., Stanworth, S. J., & Tinegate, H. (2017). Guidelines for the use of platelet transfusions. Br J Haematol, 176(3), 365-394. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjh.14423

- Schiffer, C. A., Bohlke, K., Delaney, M., Hume, H., Magdalinski, A. J., McCullough, J. J., Omel, J. L., Rainey, J. M., Rebulla, P., Rowley, S. D., Troner, M. B., & Anderson, K. C. (2018). Platelet Transfusion for Patients With Cancer: American Society of Clinical Oncology Clinical Practice Guideline Update. J Clin Oncol, 36(3), 283-299. https://doi.org/10.1200/jco.2017.76.1734

- Pavenski, K., Rebulla, P., Duquesnoy, R., Saw, C. L., Slichter, S. J., Tanael, S., & Shehata, N. (2013). Efficacy of HLA-matched platelet transfusions for patients with hypoproliferative thrombocytopenia: a systematic review. Transfusion, 53(10), 2230-2242. https://doi.org/10.1111/trf.12175

- Patel, I. J., Rahim, S., Davidson, J. C., Hanks, S. E., Tam, A. L., Walker, T. G., Wilkins, L. R., Sarode, R., & Weinberg, I. (2019). Society of Interventional Radiology Consensus Guidelines for the Periprocedural Management of Thrombotic and Bleeding Risk in Patients Undergoing Percutaneous Image-Guided Interventions-Part II: Recommendations: Endorsed by the Canadian Association for Interventional Radiology and the Cardiovascular and Interventional Radiological Society of Europe. J Vasc Interv Radiol, 30(8), 1168-1184.e1161. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvir.2019.04.017

- Hochhaus, A., Baccarani, M., Silver, R. T., Schiffer, C., Apperley, J. F., Cervantes, F., Clark, R. E., Cortes, J. E., Deininger, M. W., Guilhot, F., Hjorth-Hansen, H., Hughes, T. P., Janssen, J., Kantarjian, H. M., Kim, D. W., Larson, R. A., Lipton, J. H., Mahon, F. X., Mayer, J., . . . Hehlmann, R. (2020). European LeukemiaNet 2020 recommendations for treating chronic myeloid leukemia. Leukemia, 34(4), 966-984. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41375-020-0776-2

- Seftel, M. D., Barnett, M. J., Couban, S., Leber, B., Storring, J., Assaily, W., Fuerth, B., Christofides, A., & Schuh, A. C. (2014). A Canadian consensus on the management of newly diagnosed and relapsed acute promyelocytic leukemia in adults. Curr Oncol, 21(5), 234-250. https://doi.org/10.3747/co.21.2183

- Stanworth, S. J., Estcourt, L. J., Powter, G., Kahan, B. C., Dyer, C., Choo, L., Bakrania, L., Llewelyn, C., Littlewood, T., Soutar, R., Norfolk, D., Copplestone, A., Smith, N., Kerr, P., Jones, G., Raj, K., Westerman, D. A., Szer, J., Jackson, N., . . . TOPPS Investigators. (2013). A no-prophylaxis platelet-transfusion strategy for hematologic cancers. N Engl J Med, 368(19), 1771-1780. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1212772

- Wandt, H., Schaefer-Eckart, K., Wendelin, K., Pilz, B., Wilhelm, M., Thalheimer, M., Mahlknecht, U., Ho, A., Schaich, M., Kramer, M., Kaufmann, M., Leimer, L., Schwerdtfeger, R., Conradi, R., Dolken, G., Klenner, A., Hanel, M., Herbst, R., Junghanss, C., . . . Study Alliance, L. (2012). Therapeutic platelet transfusion versus routine prophylactic transfusion in patients with haematological malignancies: an open-label, multicentre, randomised study. Lancet, 380(9850), 1309-1316. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60689-8

- Murphy, S., Litwin, S., Herring, L. M., Koch, P., Remischovsky, J., Donaldson, M. H., Evans, A. E., & Gardner, F. H. (1982). Indications for platelet transfusion in children with acute leukemia. Am J Hematol, 12(4), 347-356. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajh.2830120406

- Stanworth, S. J., Estcourt, L. J., Llewelyn, C. A., Murphy, M. F., Wood, E. M., & Investigators, T. S. (2014). Impact of prophylactic platelet transfusions on bleeding events in patients with hematologic malignancies: a subgroup analysis of a randomized trial. Transfusion, 54(10), 2385-2393. https://doi.org/10.1111/trf.12646

- Rebulla, P., Finazzi, G., Marangoni, F., Avvisati, G., Gugliotta, L., Tognoni, G., Barbui, T., Mandelli, F., & Sirchia, G. (1997). The threshold for prophylactic platelet transfusions in adults with acute myeloid leukemia. Gruppo Italiano Malattie Ematologiche Maligne dell'Adulto. N Engl J Med, 337(26), 1870-1875. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJM199712253372602

- Heckman, K. D., Weiner, G. J., Davis, C. S., Strauss, R. G., Jones, M. P., & Burns, C. P. (1997). Randomized study of prophylactic platelet transfusion threshold during induction therapy for adult acute leukemia: 10,000/microL versus 20,000/microL. J Clin Oncol, 15(3), 1143-1149. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9060557

- Estcourt, L. J., Malouf, R., Hopewell, S., Trivella, M., Doree, C., Stanworth, S. J., & Murphy, M. F. (2017). Pathogen‐reduced platelets for the prevention of bleeding. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 30(7). https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD009072.pub3

- Slichter, S. J., Kaufman, R. M., Assmann, S. F., McCullough, J., Triulzi, D. J., Strauss, R. G., Gernsheimer, T. B., Ness, P. M., Brecher, M. E., Josephson, C. D., Konkle, B. A., Woodson, R. D., Ortel, T. L., Hillyer, C. D., Skerrett, D. L., McCrae, K. R., Sloan, S. R., Uhl, L., George, J. N., . . . Granger, S. (2010). Dose of prophylactic platelet transfusions and prevention of hemorrhage. N Engl J Med, 362(7), 600-613. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa0904084

- Fernández, K. S., & de Alarcón, P. (2013). Neonatal Thrombocytopenia. NeoReviews, 14(2), e74-e82. https://doi.org/10.1542/neo.14-2-e74

- Chen, C., Wu, S., Chen, J., Wu, J., Mei, Y., Han, T., Yang, C., Ouyang, X., Wong, M. C. M., & Feng, Z. (2022). Evaluation of the Association of Platelet Count, Mean Platelet Volume, and Platelet Transfusion With Intraventricular Hemorrhage and Death Among Preterm Infants. JAMA Netw Open, 5(10), e2237588. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.37588

- Curley, A., Stanworth, S. J., Willoughby, K., Fustolo-Gunnink, S. F., Venkatesh, V., Hudson, C., Deary, A., Hodge, R., Hopkins, V., Lopez Santamaria, B., Mora, A., Llewelyn, C., D'Amore, A., Khan, R., Onland, W., Lopriore, E., Fijnvandraat, K., New, H., Clarke, P., & Watts, T. (2019). Randomized Trial of Platelet-Transfusion Thresholds in Neonates. N Engl J Med, 380(3), 242-251. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1807320

- New, H. V., Berryman, J., Bolton-Maggs, P. H., Cantwell, C., Chalmers, E. A., Davies, T., Gottstein, R., Kelleher, A., Kumar, S., Morley, S. L., Stanworth, S. J., & British Committee for Standards in, H. (2016). Guidelines on transfusion for fetuses, neonates and older children. Br J Haematol, 175(5), 784-828. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjh.14233

- AABB. (2009). Pediatric Transfusion: A Physician’s Handbook, 3rd edition.

- Lieberman, L., Greinacher, A., Murphy, M. F., Bussel, J., Bakchoul, T., Corke, S., Kjaer, M., Kjeldsen-Kragh, J., Bertrand, G., Oepkes, D., Baker, J. M., Hume, H., Massey, E., Kaplan, C., Arnold, D. M., Baidya, S., Ryan, G., Savoia, H., Landry, D., & Shehata, N. (2019). Fetal and neonatal alloimmune thrombocytopenia: recommendations for evidence-based practice, an international approach. Br J Haematol, 185(3), 549-562. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjh.15813

- Seigeot, A., Desmarets, M., Rumpler, A., Leroux, F., Deconinck, E., Monnet, E., & Bardiaux, L. (2018). Factors related to the outcome of prophylactic platelet transfusions in patients with hematologic malignancies: an observational study. Transfusion, 58(6), 1377-1387. https://doi.org/10.1111/trf.14592

- Nahirniak, S., Slichter, S. J., Tanael, S., Rebulla, P., Pavenski, K., Vassallo, R., Fung, M., Duquesnoy, R., Saw, C. L., Stanworth, S., Tinmouth, A., Hume, H., Ponnampalam, A., Moltzan, C., Berry, B., Shehata, N., & International Collaboration for Transfusion Medicine Guidelines. (2015). Guidance on platelet transfusion for patients with hypoproliferative thrombocytopenia. Transfus Med Rev, 29(1), 3-13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tmrv.2014.11.004

- Murphy, M. F., Brozovic, B., Murphy, W., Ouwehand, W., & Waters, A. H. (1992). Guidelines for platelet transfusions. British Committee for Standards in Haematology, Working Party of the Blood Transfusion Task Force. Transfus Med, 2(4), 311-318. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/1339584

- Cid, J., Lozano, M., Ziman, A., West, K. A., O'Brien, K. L., Murphy, M. F., Wendel, S., Vazquez, A., Ortin, X., Hervig, T. A., Delaney, M., Flegel, W. A., Yazer, M. H., & Biomedical Excellence for Safer Transfusion, c. (2015). Low frequency of anti-D alloimmunization following D+ platelet transfusion: the Anti-D Alloimmunization after D-incompatible Platelet Transfusions (ADAPT) study. Br J Haematol, 168(4), 598-603. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjh.13158

- Lozano, M., & Cid, J. (2003). The clinical implications of platelet transfusions associated with ABO or Rh(D) incompatibility. Transfus Med Rev, 17(1), 57-68. https://doi.org/10.1053/tmrv.2003.50003

- Cid, J., Ortin, X., Elies, E., Castella, D., Panades, M., & Martin-Vega, C. (2002). Absence of anti-D alloimmunization in hematologic patients after D-incompatible platelet transfusions. Transfusion, 42(2), 173-176. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11896331

- O'Brien, K. L., Haspel, R. L., & Uhl, L. (2014). Anti-D alloimmunization after D-incompatible platelet transfusions: a 14-year single-institution retrospective review. Transfusion, 54(3), 650-654. https://doi.org/10.1111/trf.12341

- The Trial to Reduce Alloimmunization to Platelets Study Group. (1997). Leukocyte reduction and ultraviolet B irradiation of platelets to prevent alloimmunization and refractoriness to platelet transfusions. . N Engl J Med, 337(26), 1861-1869. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJM199712253372601

- Public Health Agency of Canada. Supplement guideline for investigation of suspected transfusion transmitted bacterial contamination. Canada Communicable Disease Report 2008; 34S1:1-8. http://www.phac-aspc.gc.ca/hcai-iamss/index-eng.php

- Yazer, M. H., Podlosky, L., Clarke, G., & Nahirniak, S. M. (2004). The effect of prestorage WBC reduction on the rates of febrile nonhemolytic transfusion reactions to platelet concentrates and RBC. Transfusion, 44(1), 10-15. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/14692961

- Popovsky, M. A. (2007). Transfusion Reactions (3rd Edition ed.).

- Pavenski, K., Webert, K. E., & Goldman, M. (2008). Consequences of transfusion of platelet antibody: a case report and literature review. Transfusion, 48(9), 1981-1989. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1537-2995.2008.01796.x

- Callum, J., Lin, Y., Pinkerton, P. H., Karkouti, K., Pendergrast, J. M., Robitaille, N., Tinmouth, A. T., & Webert, K. (2011). Bloody easy 3, blood transfusions, blood alternatives and transfusion reactions: a guide to transfusion medicine. (3rd edition ed.). http://transfusionontario.org/en/cmdownloads/categories/bloody_easy/

- Canadian Blood Services. (2022). Circular of Information, Pooled Platelets LR CPD, Apheresis Platelets,. Retrieved September 12 from https://www.blood.ca/en/hospital-services/products/component-types/circular-information

- Bishop, J. F., Matthews, J. P., Yuen, K., McGrath, K., Wolf, M. M., & Szer, J. (1992). The definition of refractoriness to platelet transfusions. Transfus Med, 2(1), 35-41. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/1308461

- Stanworth, S. J., Navarrete, C., Estcourt, L., & Marsh, J. (2015). Platelet refractoriness--practical approaches and ongoing dilemmas in patient management. Br J Haematol, 171(3), 297-305. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjh.13597

- Sullivan, J. C., & Peña, J. R. (2022). Use of Human Leukocyte Antigen (HLA)-Incompatible Platelet Units in HLA Platelet-Refractory Patients With Limited Number of or Low-Level HLA Donor-Specific Antibodies Results in Permissive Transfusions. Arch Pathol Lab Med, 146(10), 1243-1251. https://doi.org/10.5858/arpa.2021-0051-OA

- Karafin, M. S., Schumacher, C., Zhang, J., Simpson, P., Johnson, S. T., & Pierce, K. L. (2021). Human leukocyte antigen (HLA)-incompatible mean fluorescence intensity-selected platelet products have corrected count increments similar to HLA antigen-matched platelets. Transfusion, 61(8), 2307-2316. https://doi.org/10.1111/trf.16430

- Williamson, L. M., Stainsby, D., Jones, H., Love, E., Chapman, C. E., Navarrete, C., Lucas, G., Beatty, C., Casbard, A., & Cohen, H. (2007). The impact of universal leukodepletion of the blood supply on hemovigilance reports of posttransfusion purpura and transfusion-associated graft-versus-host disease. Transfusion, 47(8), 1455-1467. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1537-2995.2007.01281.x

- Menis, M., Forshee, R. A., Anderson, S. A., McKean, S., Gondalia, R., Warnock, R., Johnson, C., Mintz, P. D., Worrall, C. M., Kelman, J. A., & Izurieta, H. S. (2015). Posttransfusion purpura occurrence and potential risk factors among the inpatient US elderly, as recorded in large Medicare databases during 2011 through 2012. Transfusion, 55(2), 284-295. https://doi.org/10.1111/trf.12782

- Politis, C., Wiersum-Osselton, J., Richardson, C., Grouzi, E., Sandid, I., Marano, G., Goto, N., Condeço, J., Boudjedir, K., Asariotou, M., Politi, L., & Land, K. (2022). Adverse reactions following transfusion of blood components, with a focus on some rare reactions: Reports to the International Haemovigilance Network Database (ISTARE) in 2012-2016. Transfus Clin Biol, 29(3), 243-249. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tracli.2022.03.005

- Woelke, C., Eichler, P., Washington, G., & Flesch, B. K. (2006). Post-transfusion purpura in a patient with HPA-1a and GPIa/IIa antibodies. Transfus Med, 16(1), 69-72. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-3148.2005.00633.x

- Mueller-Eckhardt, C., & Kiefel, V. (1988). High-dose IgG for post-transfusion purpura-revisited. Blut, 57(4), 163-167. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/3139110

- Taaning, E., & Tonnesen, F. (1999). Pan-reactive platelet antibodies in post-transfusion purpura. Vox Sang, 76(2), 120-123. https://doi.org/31031

- Hawkins, J., Aster, R. H., & Curtis, B. R. (2019). Post-Transfusion Purpura: Current Perspectives. J Blood Med, 10, 405-415. https://doi.org/10.2147/JBM.S189176

- Delaney, M., Wendel, S., Bercovitz, R. S., Cid, J., Cohn, C., Dunbar, N. M., Apelseth, T. O., Popovsky, M., Stanworth, S. J., Tinmouth, A., Van De Watering, L., Waters, J. H., Yazer, M., & Ziman, A. (2016). Transfusion reactions: prevention, diagnosis, and treatment. Lancet, 388(10061), 2825-2836. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(15)01313-6