This annual report describes surveillance of transmissible blood-borne infections and emerging threats of concern during the calendar year of 2024. High quality and timely surveillance are essential to the safety of the blood supply. Monitoring of transmissible disease markers that the blood is tested for are central to surveillance, as is investigation of any reports of possible transfusion transmission. Horizon scanning for any new pathogens that may pose a risk ensures ongoing preparedness. Non-infectious surveillance of aspects of donor health and safety are also included.

Infectious risk monitoring

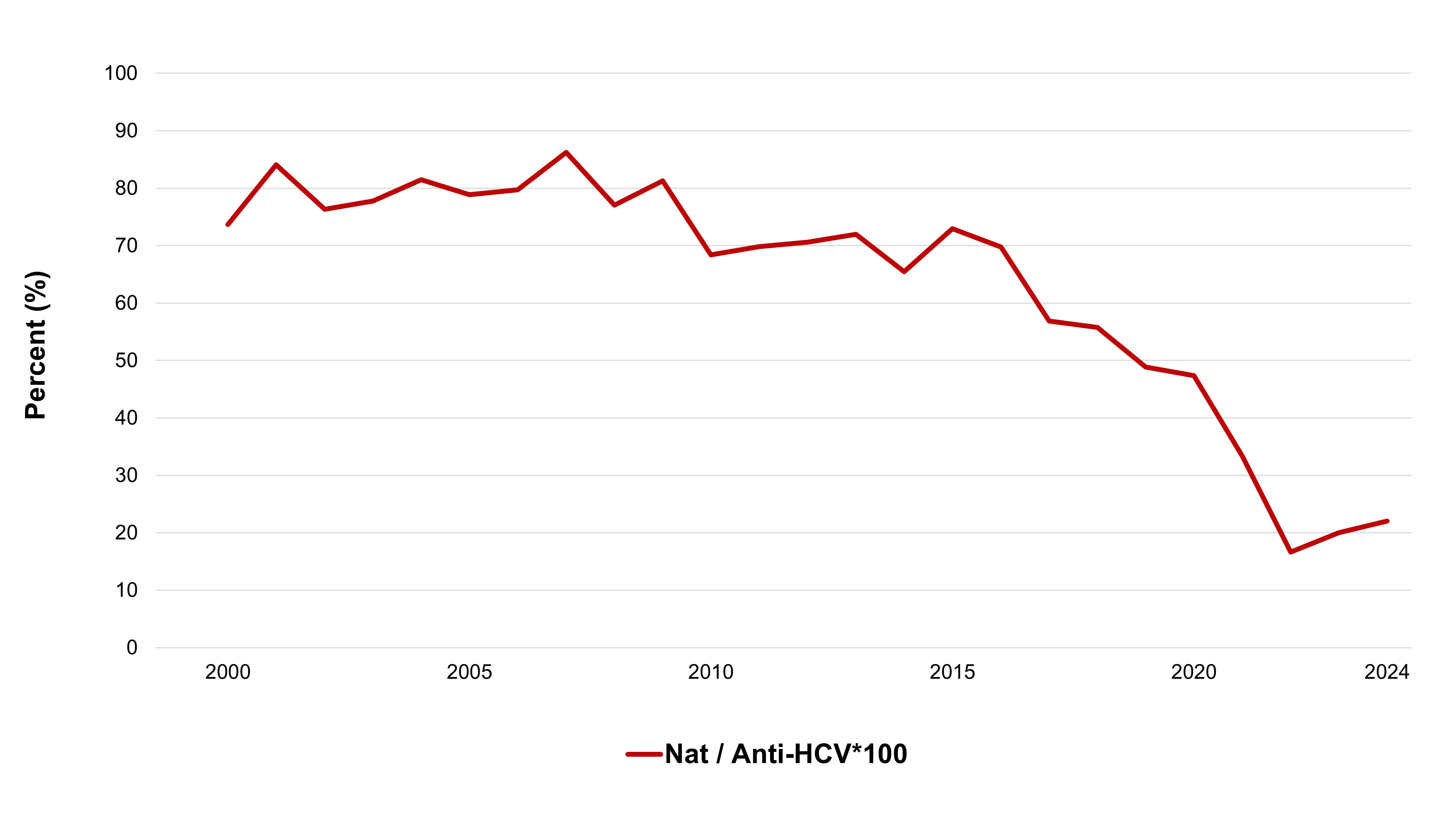

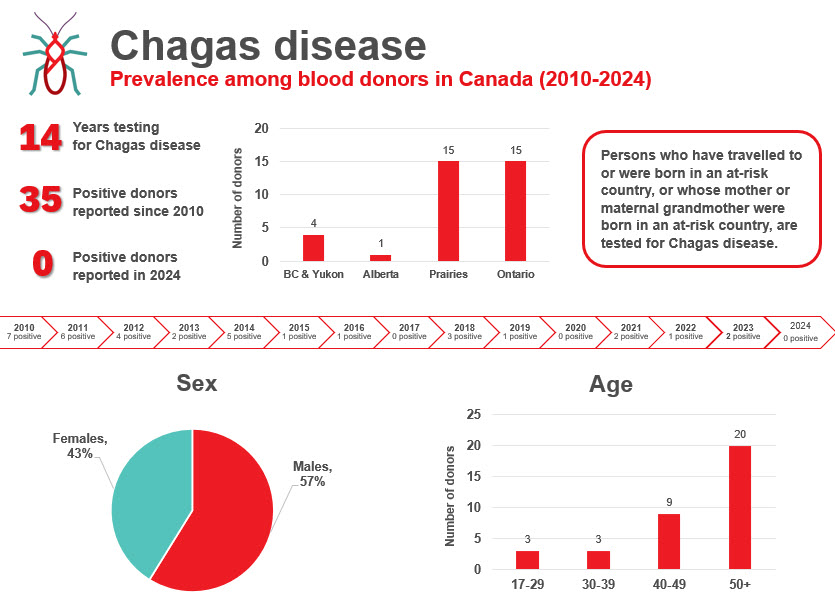

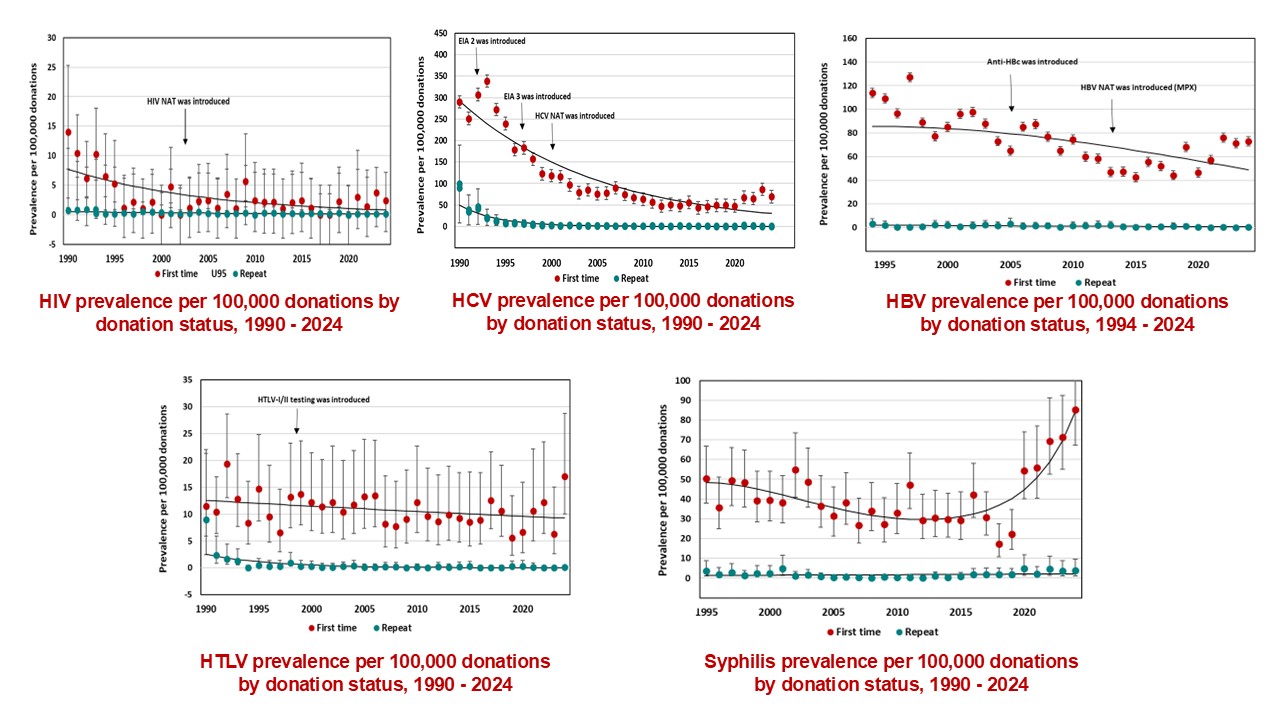

The most up-to-date tests for pathogens are used to identify infectious donations and prevent their release for patient use. In 2024, transmissible disease rates per 100,000 allogeneic donations (for direct blood transfusion) continued to be very low: human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) 0.4, hepatitis C (HCV) 7.3, hepatitis B (HBV) 8.0, human T-cell lymphotropic virus (HTLV) 1.9 and syphilis 12.2. Selective testing of donors at risk of Chagas disease identified no positive donations, and there were six donations that were positive for West Nile virus (WNV) similar to previous years. Residual risk estimates of a potentially infectious donation from a unit of blood are very low at one in 13.2 million donations for HIV, one in 72.1 million donations for HCV and one in 4.1 million donations for HBV. Lookback and traceback investigations did not identify any transfusion transmitted infections. Since 2016 nearly half of HIV positive donations were non-B subtype which is the subtype more common in heterosexuals. The most common HBV genotype was D, followed by A, B and C. These genotypes are common in particular parts of the world and likely reflect the diversity of immigrants in Canada. The most common HCV genotypes were one and three. The viral genotypes observed in donors are not dissimilar from the Canadian general population.

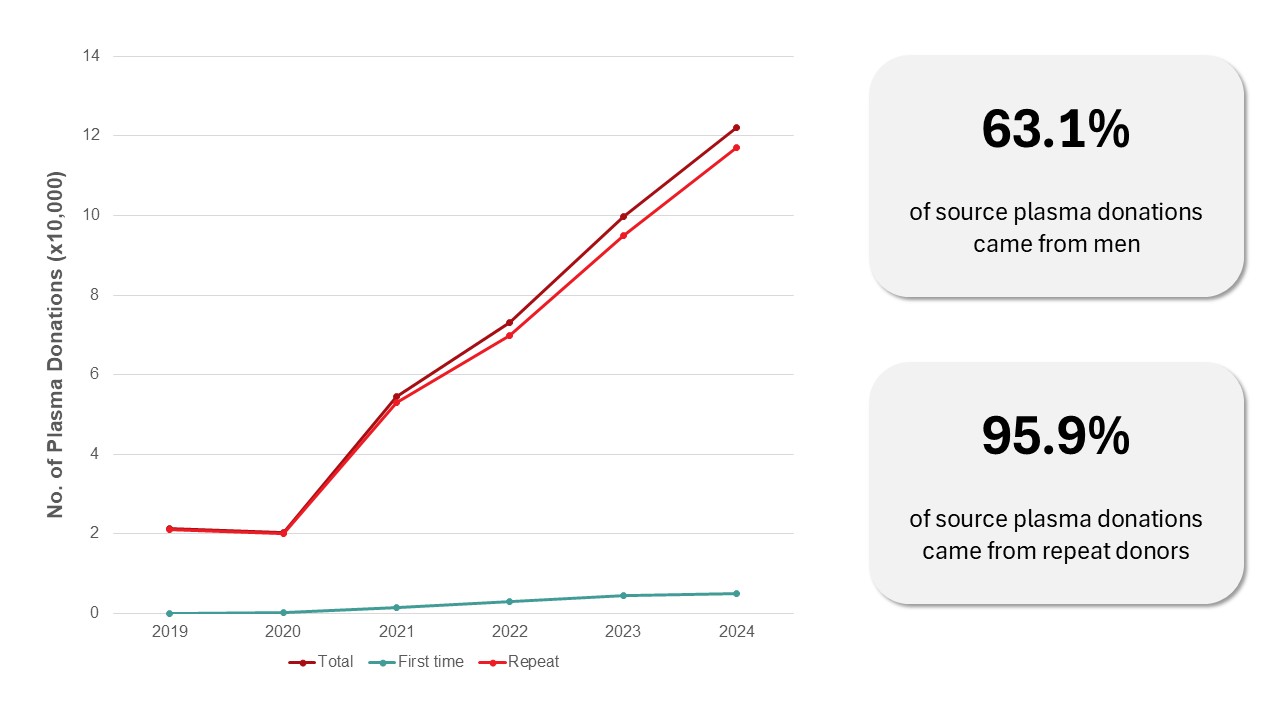

Source plasma is collected by apheresis to be sent for manufacturing fractionated plasma products such as intravenous immune gammaglobulins (IVIG) and albumin. In 2024, 122,214 source plasma donations were collected, mostly from repeat donors (96 per cent). Transmissible disease rates per 100,000 source plasma donations were very low: HIV 0, hepatitis C (HCV) 2.5, hepatitis B (HBV) 7.4 and syphilis 3.3.

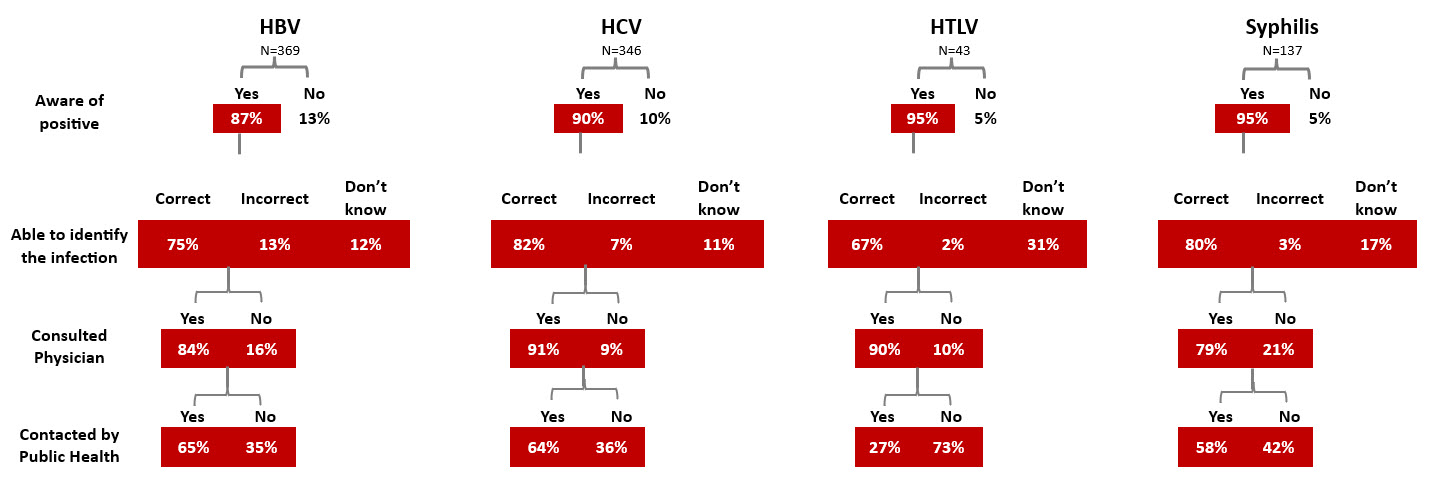

All donors whose donation tests positive for a transfusion transmissible infection are informed by letter, and sometimes by telephone. Interviews of donors after they were notified of their positive test showed that notification was effective as most donors were aware of their positive test. Most were surprised by the positive test, and most sought medical care.

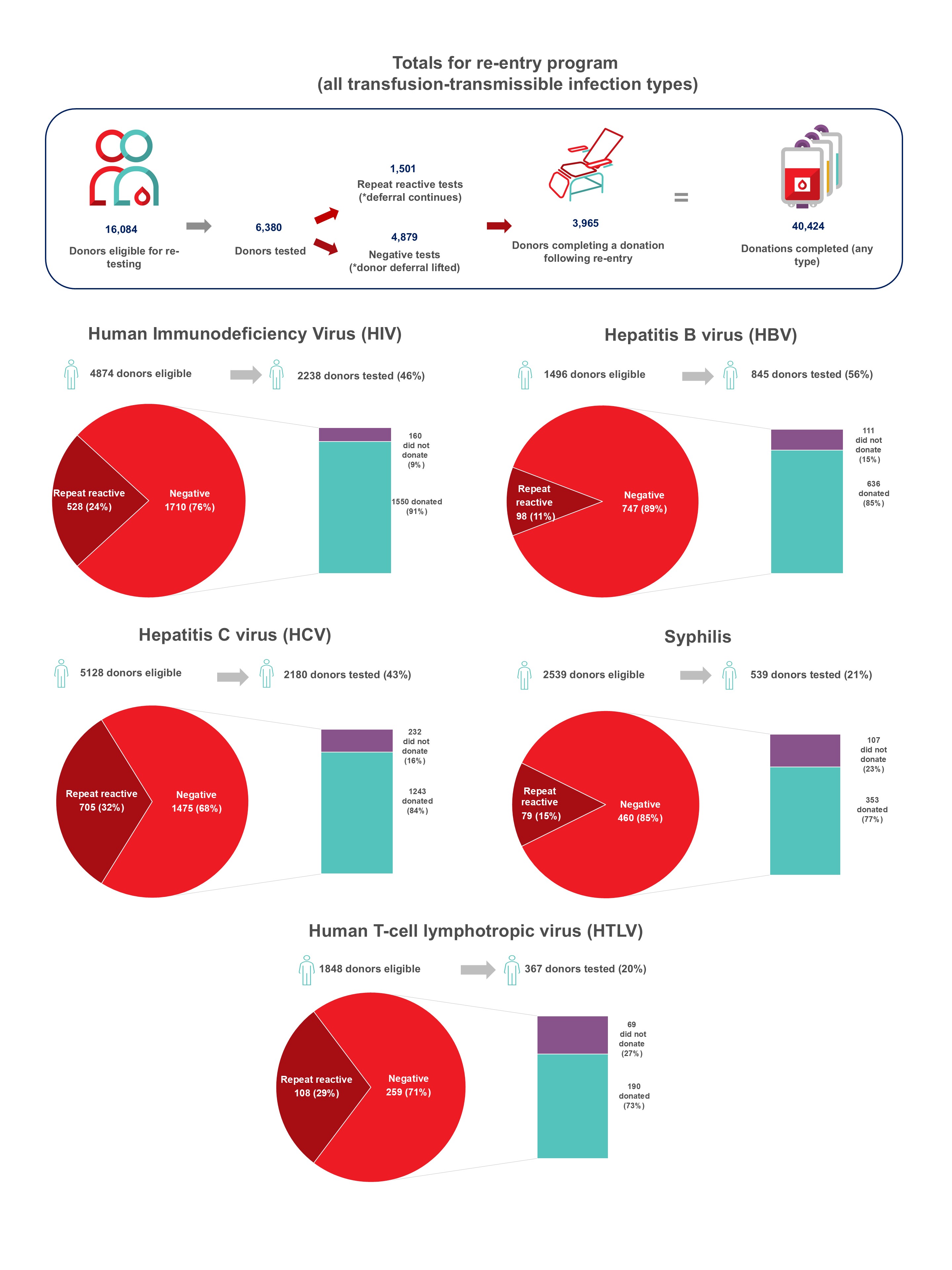

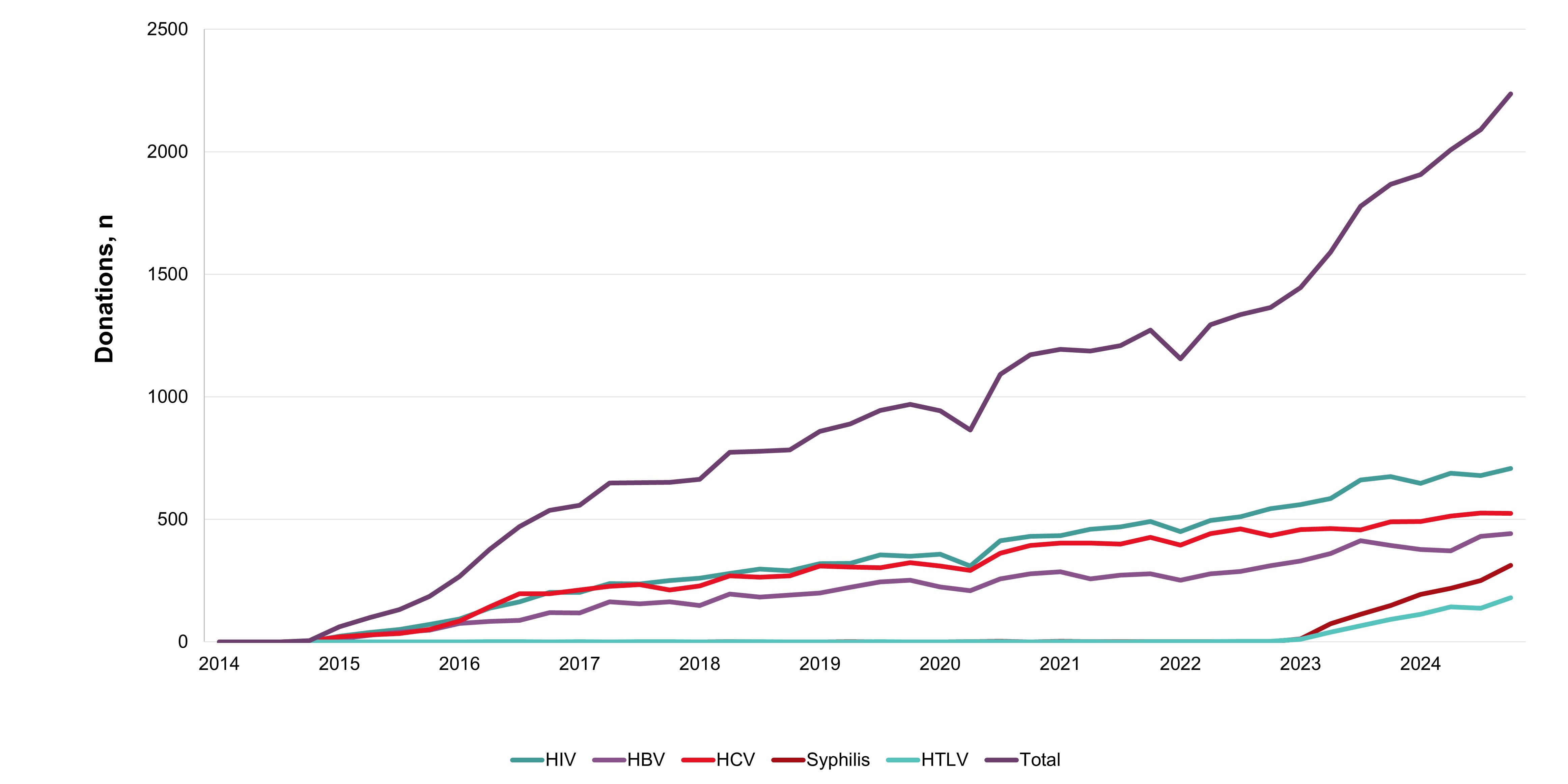

In 2024, whole blood derived buffy coat platelets were being pathogen reduced in all regions all but eliminating the risk of bacterial contamination and by May 2024 apheresis platelets were also pathogen reduced. Non-pathogen reduced platelets are distributed on rare occasions for clinical contra-indications to pathogen reduction additives. Bacterial growth was identified in four apheresis platelet products that had not been pathogen reduced up until May. Of 495 potential peripheral blood stem cell or bone marrow donors tested, none were positive for any infectious marker. Of 290 samples from mothers donating stem cells collected from the umbilical cord and placenta (called cord blood) after their babies were born, none were positive for any infectious markers. Since 2014 donors with false reactive/unconfirmed results for HIV, HCV or HBV have been eligible to give a re-entry testing sample after six months, and if all infectious tests are negative, they may re-commence donating. As of Jan. 16, 2023, the donor re-entry program was also extended to donors who had previously tested false reactive for HTLV or syphilis. As of Dec. 31, 2024, nearly 4,000 donors have been able to donate again and have given over 40,000 donations. The donor re-entry program supports a safe blood system and provides a positive contribution to the active donor base. After removal of deferral for time spent in countries with former risk of variant Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease, over 13,000 previously deferred donors have returned, and about 8000 new donors donated due to the deferral change.

Horizon scanning

Horizon scanning activities have historically occurred at Canadian Blood Services with the maintenance of blood and stem cell emerging pathogen matrices, as well as quarterly reports. These activities collect information on a variety of variables that allow for Canadian Blood Services to prepare and plan for changing risks to blood safety and sufficiency. Since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, Canadian Blood Services has noted a changing information landscape which became increasingly acute in late 2024. In 2024, Canadian Blood Services began planning to integrate a horizon scanning function into the developing Surveillance and Discovery Laboratory (SDL) functions. This work continues on into 2025.

The risk of a tick-borne disease, babesiosis, continues to be monitored. The parasite (Babesia microti) that causes babesiosis appears to be in the early stages of becoming established in a few places in Canada, especially in Manitoba. Travelers and former residents from malaria risk areas are temporarily deferred for malaria risk. In addition, a three-week deferral for any travel outside Canada, continental U.S., Hawaii and continental Europe reduces risk from short term travel related infections such as Zika virus.

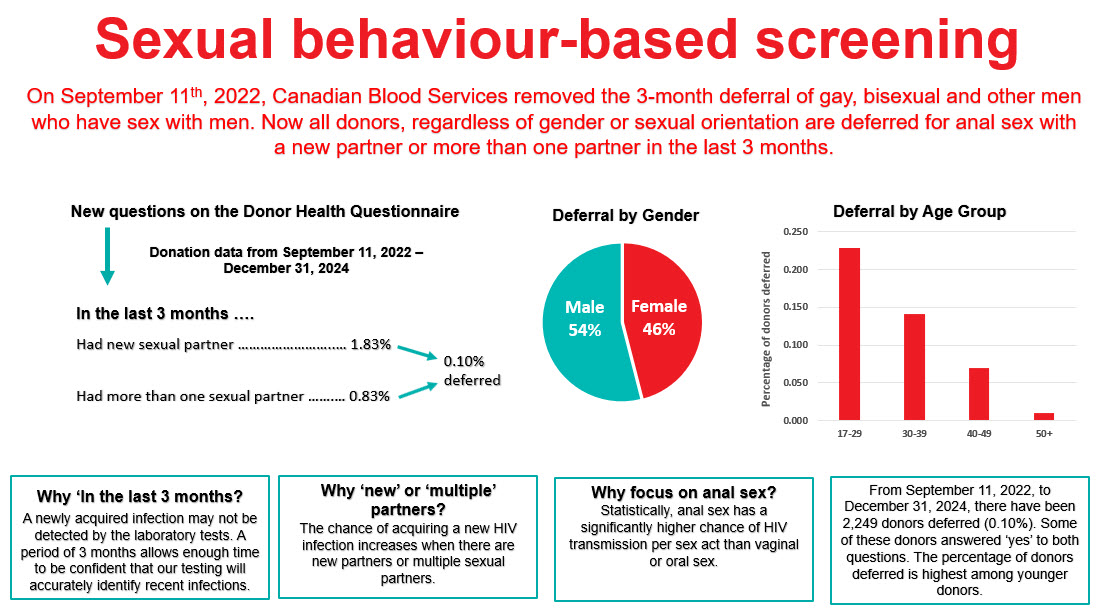

Sexual behaviour-based screening

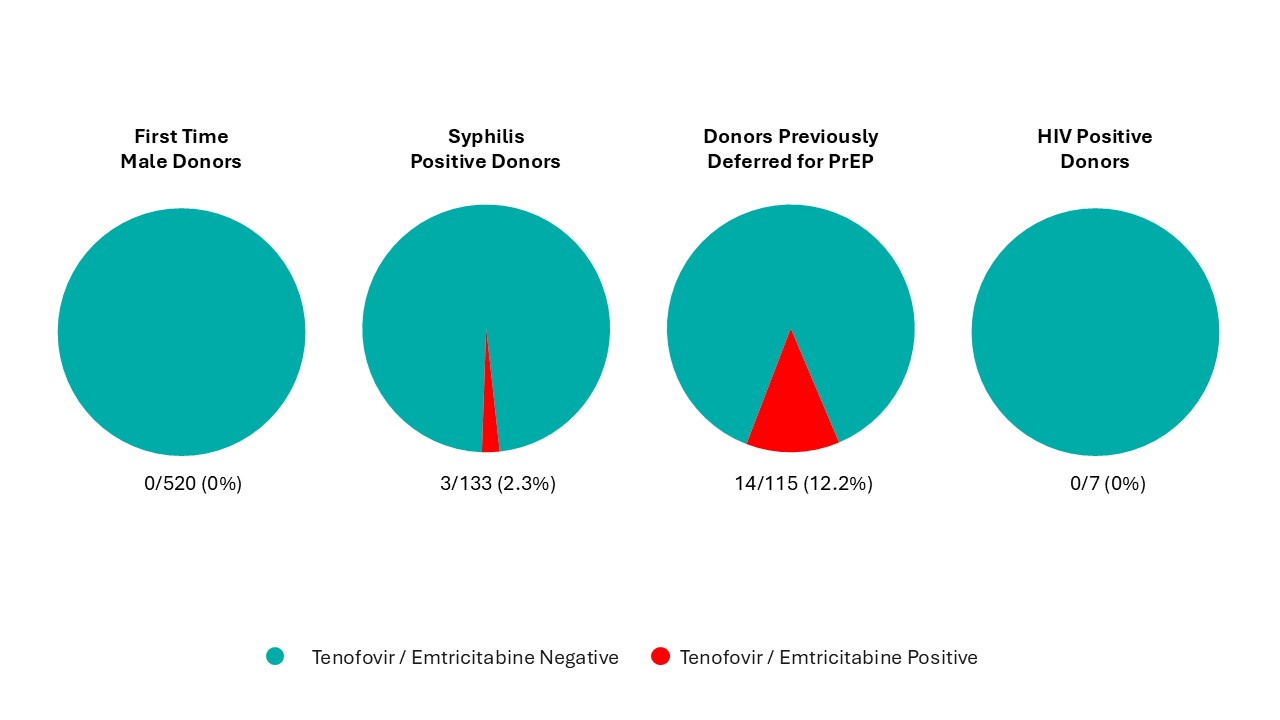

On Sept. 11, 2022, the three-month deferral for gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men was removed and replaced with deferral based on sexual risk questions that all donors must answer regardless of their gender or sexual orientation. Since implementation, seven allogeneic blood donations and one source plasma donations were HIV positive, with a similar HIV positivity rate as prior to the criteria change. Since implementation, 0.1 per cent of donors were temporarily deferred using these new sexual behaviour-based questions. Pre- and post-implementation donor compliance surveys showed compliance with the new screening questions was suboptimal. In the survey there were 0.86 per cent of donors who answered yes to the sexual risk questions before they were implemented (when most were eligible to donate) and 0.76 per cent after implementing when they should have been deferred. Pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) medication is used to prevent HIV infection in at-risk individuals. Donors are deferred for oral use of PrEP in the last four months (injectable PrEP, which was approved for use in Canada in May 2024, carries a two year deferral) due to risk of false negative tests. Testing of selected donation samples for PrEP showed no evidence of PrEP use in first time male donors or HIV positive donors, but 2.3 per cent of syphilis positive donation samples and 12.2 per cent of donation samples from donors who had been deferred for PrEP use on a prior donation had positive results for PrEP. This demonstrates the difficulty of messages about PrEP use and donation which is contrary to messaging from their health care provider and public health about reducing their risk of HIV by taking PrEP. However, in spite of non-compliance shown by these two studies, HIV rates in donors to date have remained stable and low as noted above.

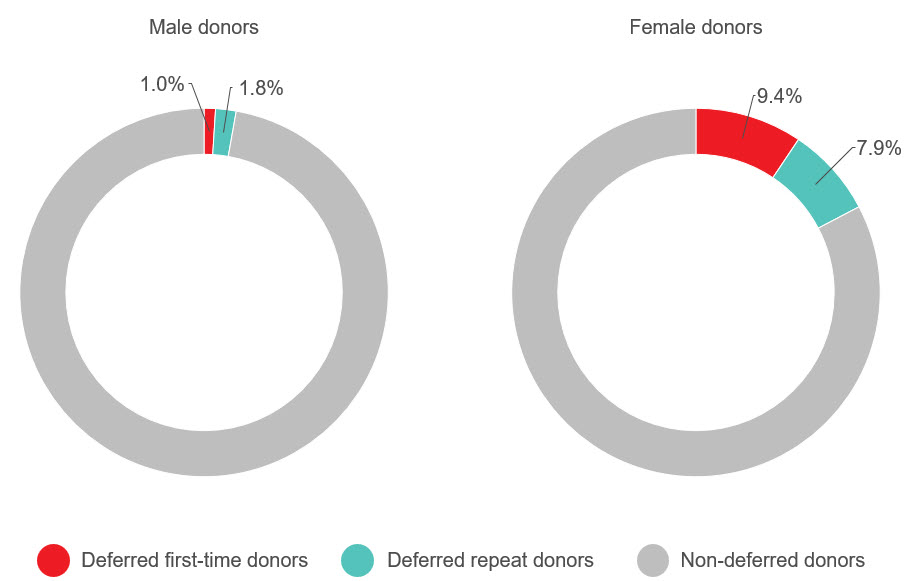

Donor safety

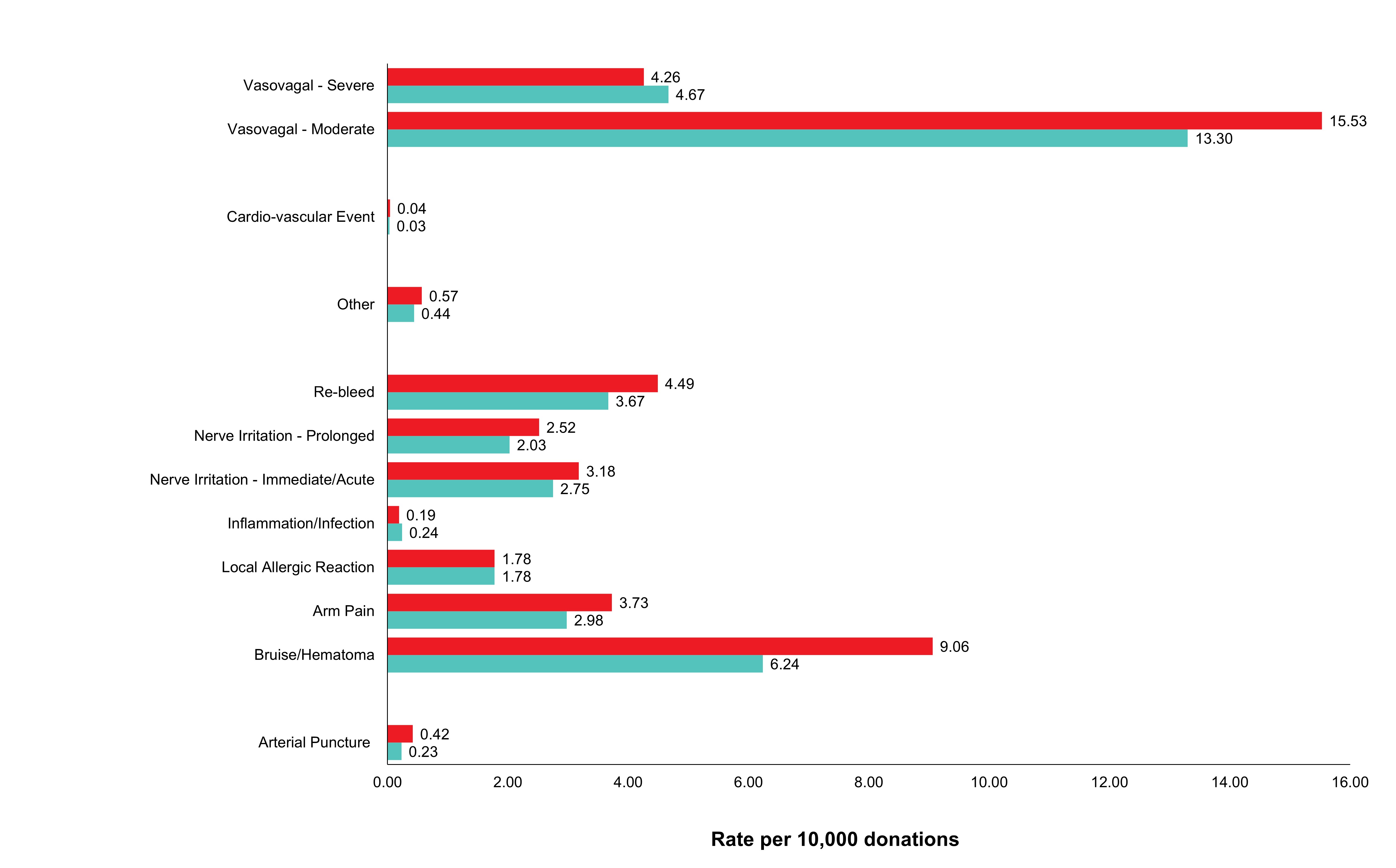

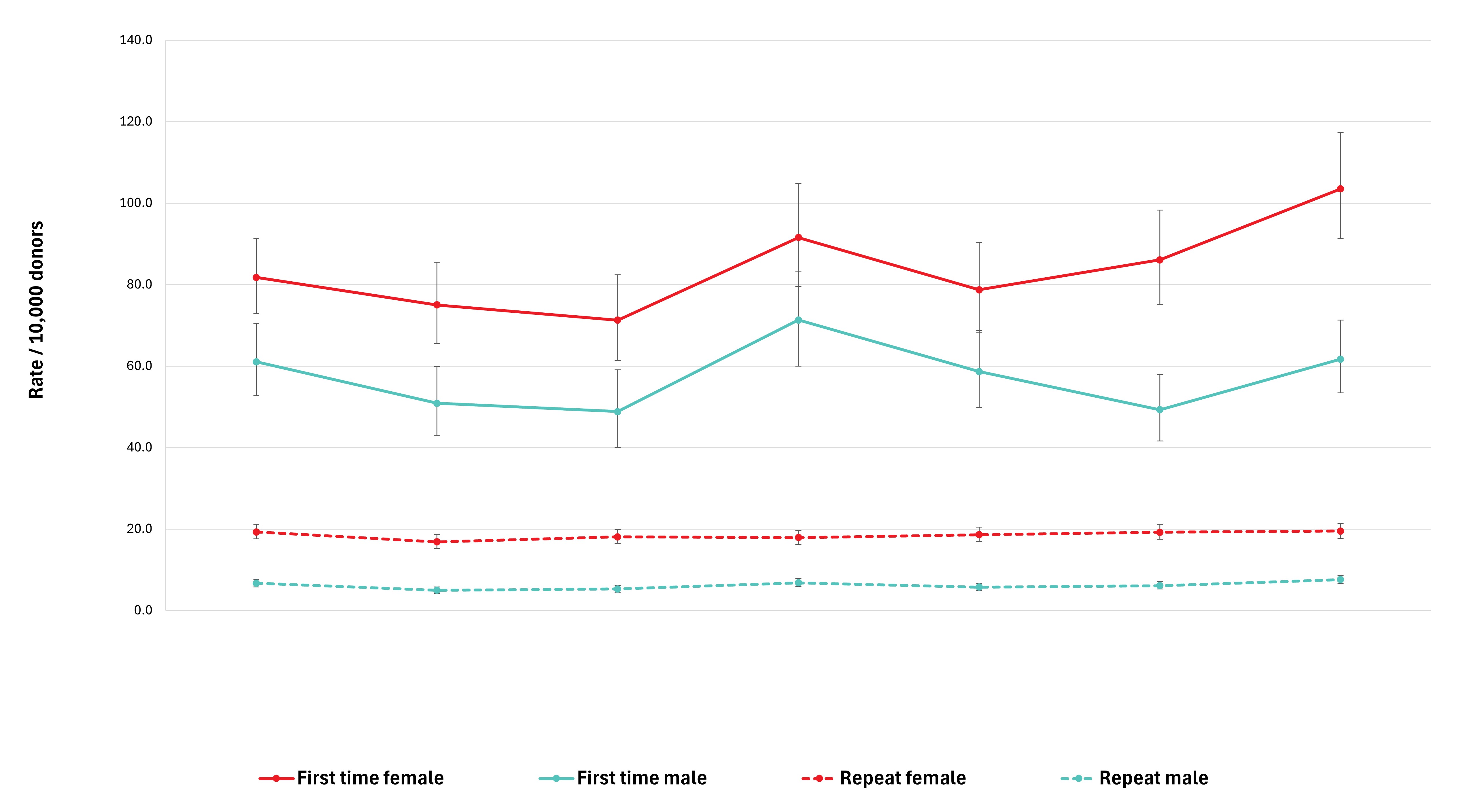

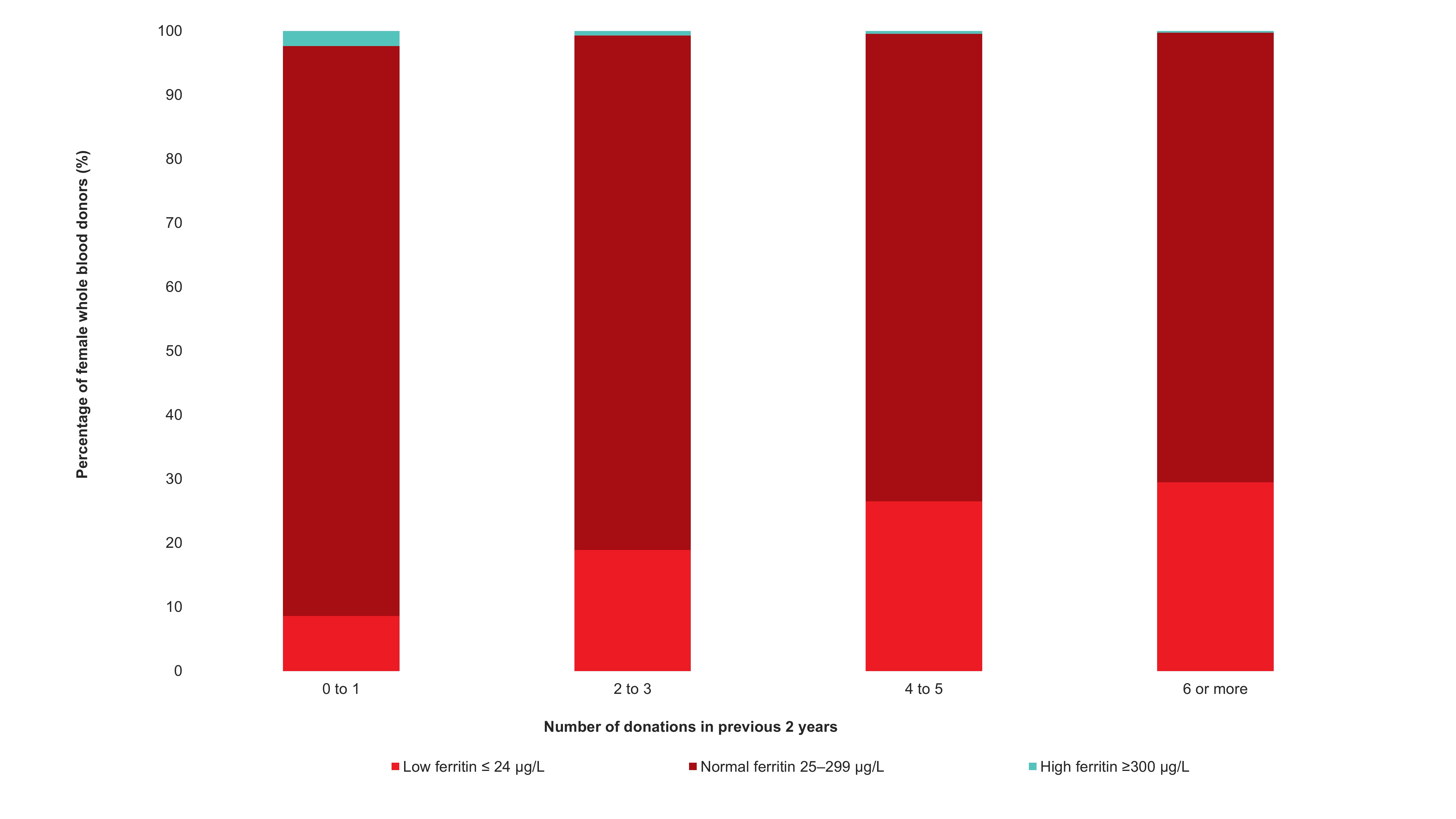

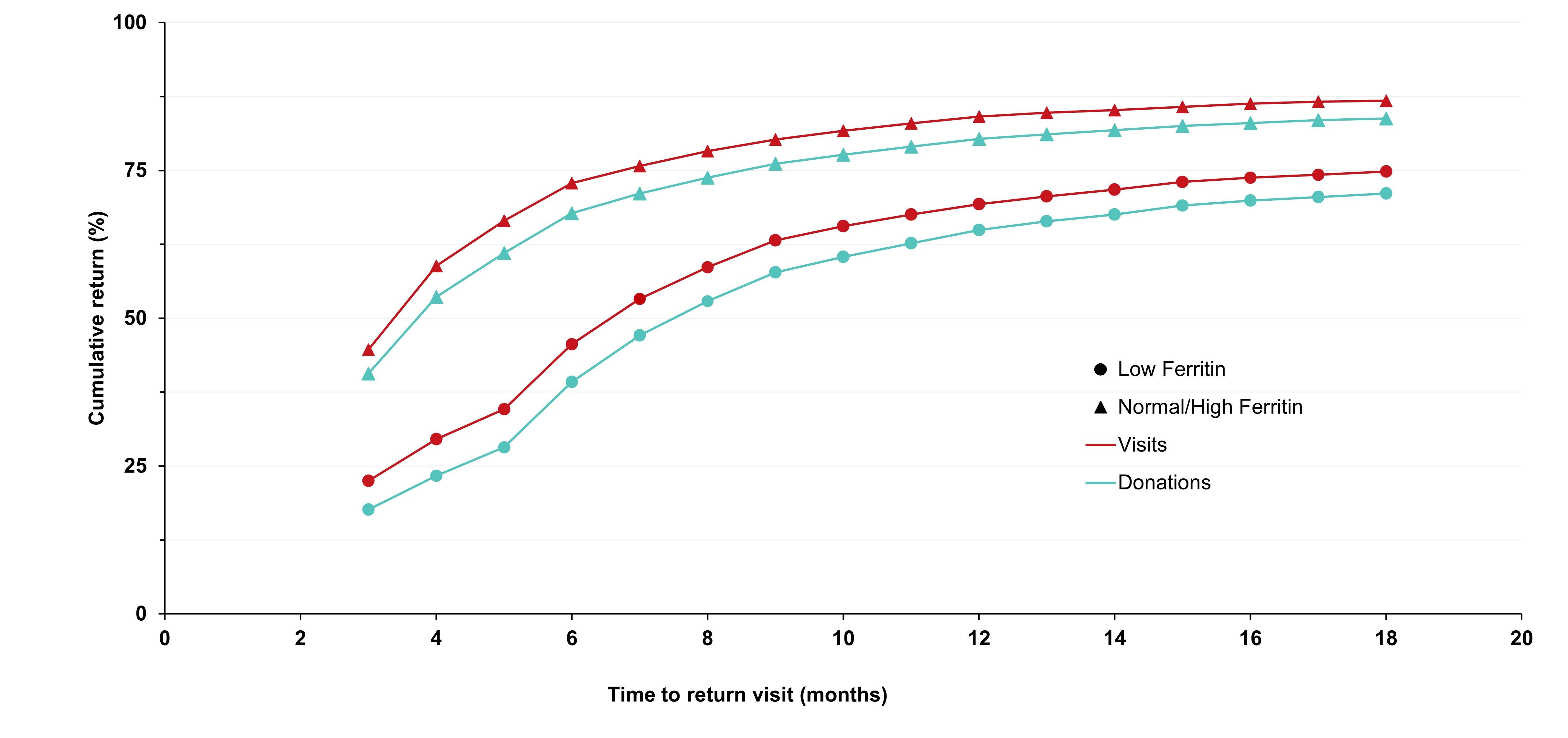

Adverse reactions to donation are rare. The most common reactions are vasovagal (fainting) and bruising. Vasovagal reactions are more common in first time donors and younger females. Deferrals for low hemoglobin are higher in females than males. The inter-donation interval for whole blood donations in females is longer than for males (84 vs 56 days) to allow more time for females to recoup their body iron levels. Starting in 2023 female donors on their 10th, 20th, or 30th etc., donations were tested for ferritin, a measure of body iron status that can indicate low body iron levels before hemoglobin drops. If ferritin was low (≤ 24 µg/L), donors were advised not to donate for at least six months and to see their health care practitioner for further testing and advice about iron supplementation. About a quarter of these female donors had low ferritin in spite of passing their hemoglobin test on donation. Low ferritin was associated with more frequent donation. After 18 months, 75 per cent of donors who had low ferritin returned compared with 86 per cent with normal/high ferritin. Deferral for low hemoglobin was reduced with longer time to return. To ensure ongoing donor iron health, ferritin testing is important for safeguarding donors.

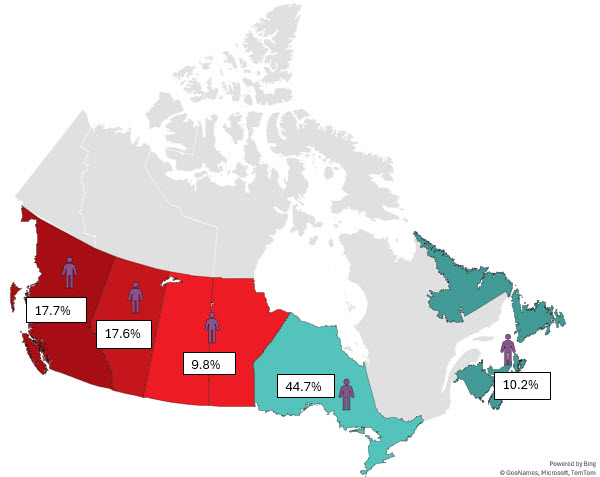

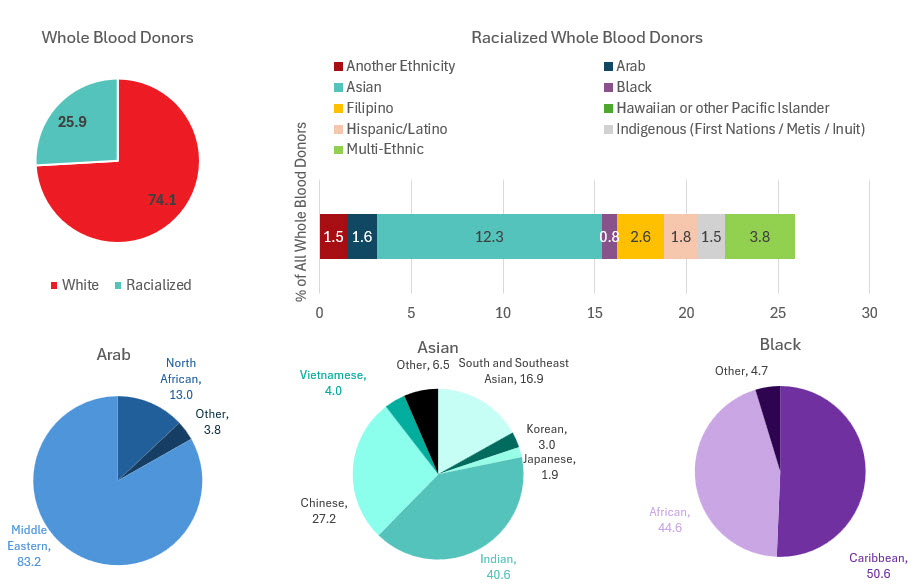

Donor demographics

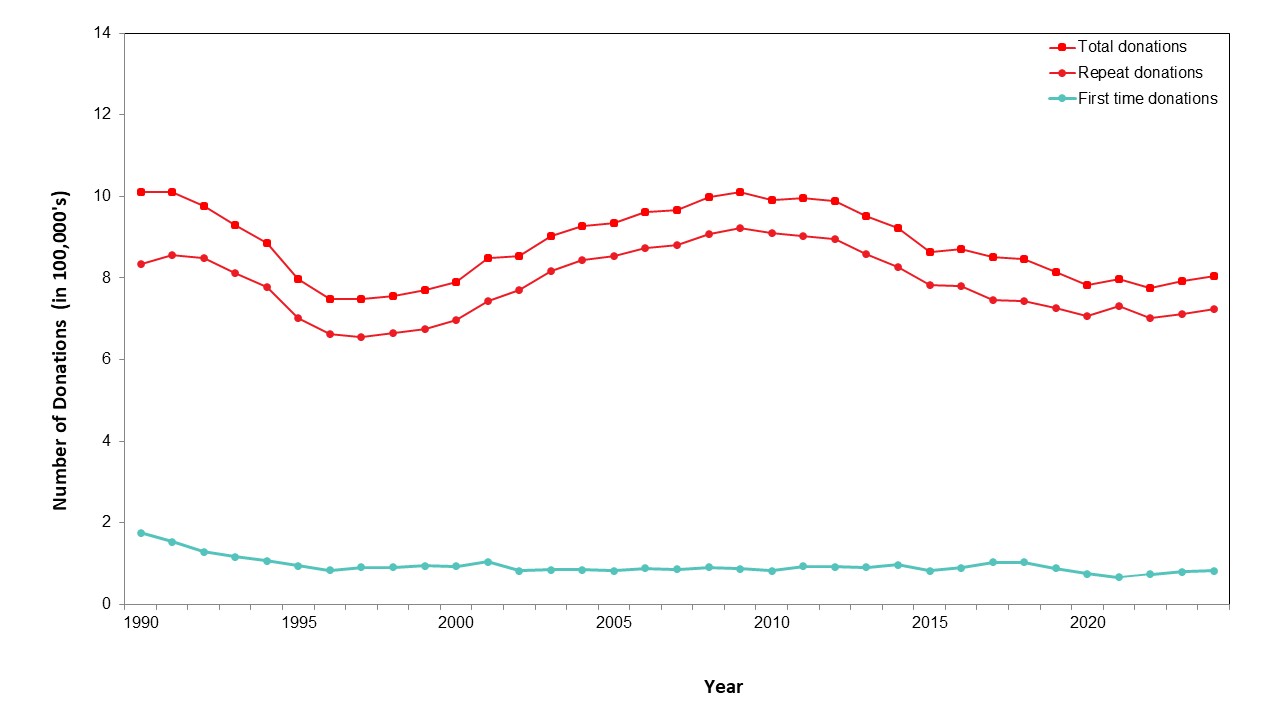

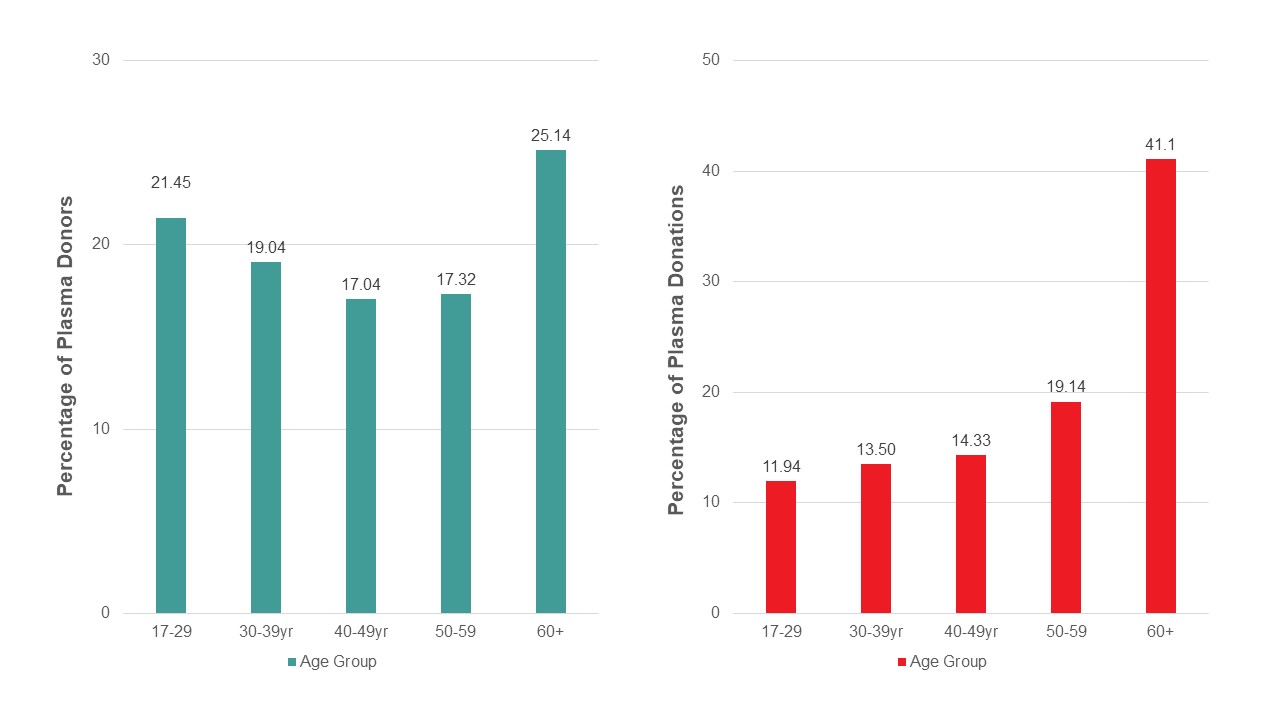

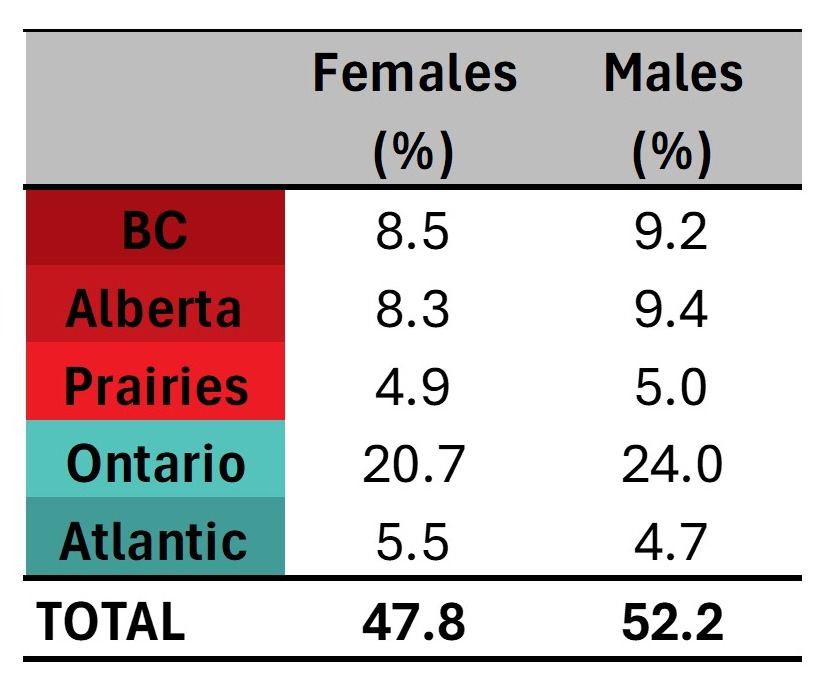

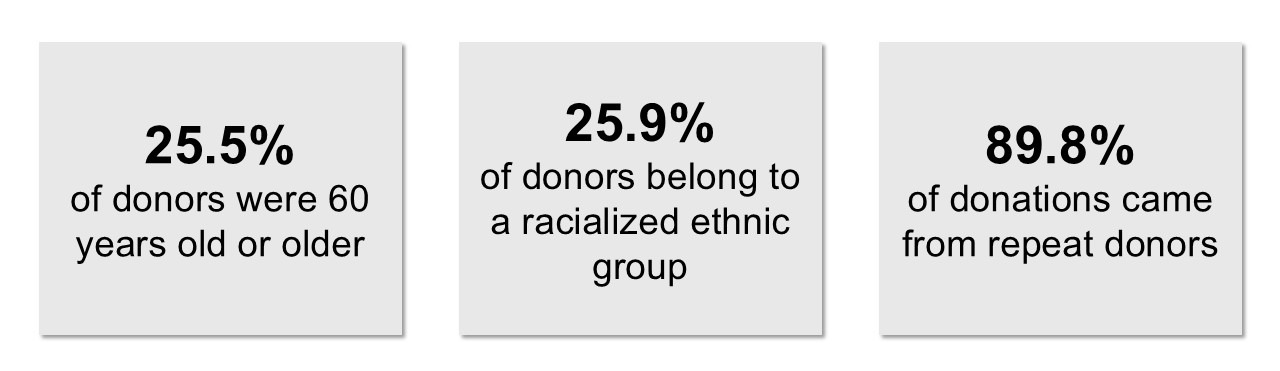

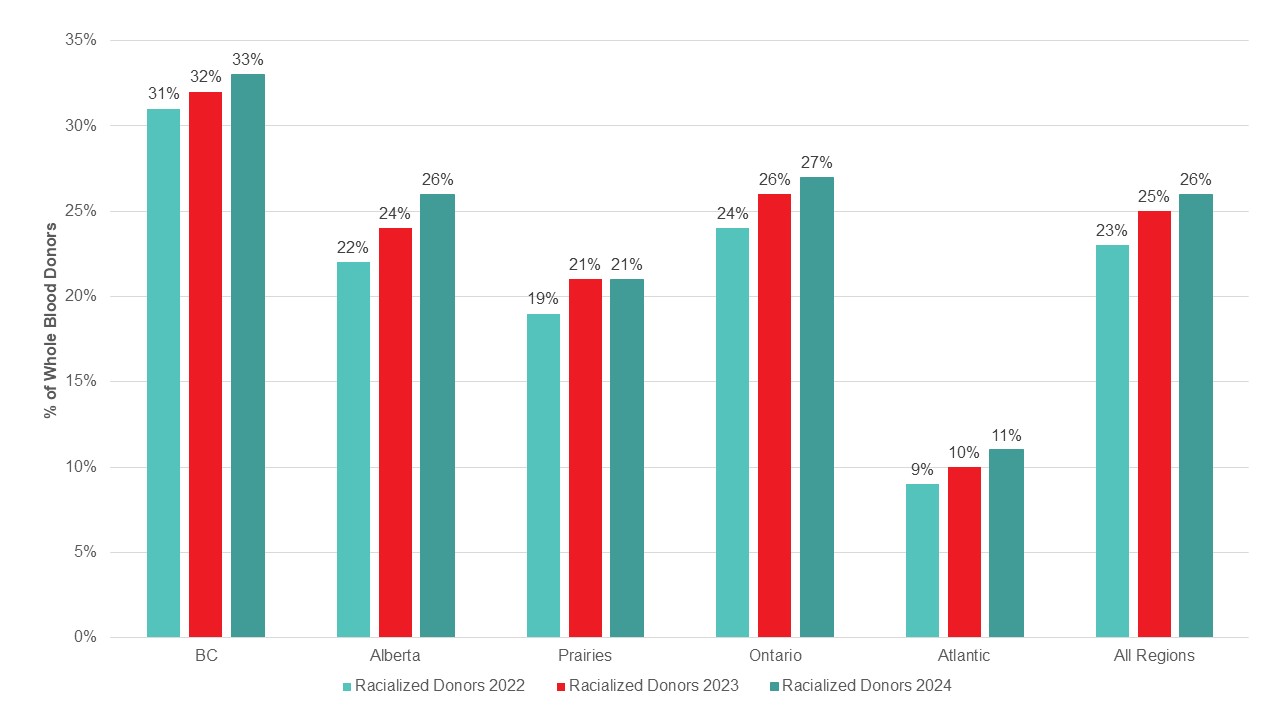

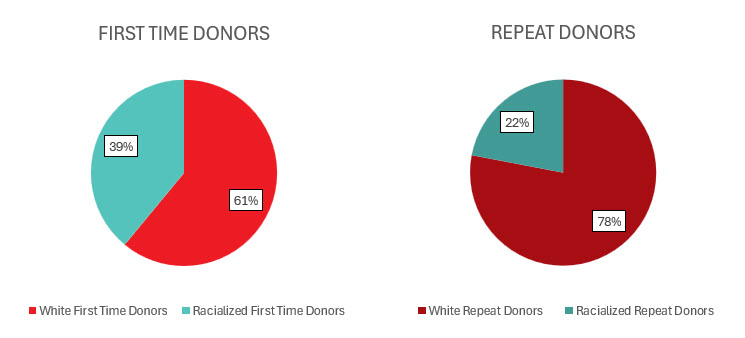

Most whole blood donations are from repeat donors. A little more than half of donors are males, and about a quarter are persons 60 years of age or older. About 45 per cent of donations are from Ontario. Based on responses to a voluntary question about race/ethnicity over a quarter of whole blood donations are from Black, Indigenous and Racialized donors. Most source plasma donations are from repeat donors. While a quarter of source plasma donors are aged 60 and over, they donated about 40 per cent of donations. A little over half of donations are from Ontario. Just under a quarter are from Black, Indigenous and Racialized donors.