Chapter 1

Vein to vein: A summary of the blood system in Canada

Background

A robust blood system is critical to the functioning of the Canadian health-care system. The availability of blood components and blood products is a prerequisite for various health-care services — including surgeries, cancer treatments and other acute and chronic medical conditions, trauma care, organ transplantation, and childbirths — that extend life and improve outcomes for many patients annually.1

The tainted-blood tragedy2 of the 1980s and 1990s left thousands of Canadians infected with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and hepatitis C virus (HCV). This tragedy led to the Royal Commission of Inquiry on the Blood System in Canada. In 1997, Justice Krever tabled his report in the House of Commons, putting forward a set of 50 recommendations.3 That same year, federal, provincial and territorial governments (excluding Quebec) entered into a memorandum of understanding to outline the renewed national blood system, including their relationship with the national blood authority, its function, and structure.

In 1998, Canadian Blood Services was created as the national blood authority. The provincial and territorial ministers of health (excluding Quebec) took the role of the corporate members of Canadian Blood Services. The ministries of health provided most of the financial support, and governments were identified as primary funders. An extensive framework of advisory and liaison committees was established to ensure communication between parties including engagement from the medical, recipient and donor communities.

At the same time, the Quebec government passed the Act respecting Héma-Québec and the biovigilance committee, CQLR c H-1.1, that created Héma-Québec as the blood authority for the province of Quebec. The act also established a biovigilance committee to advise the Quebec government on risks relating to the blood system. For both Canadian Blood Services and Héma-Québec, the federal government has regulatory oversight of the collection, processing, testing and distribution of blood components (e.g., red blood cells, platelets and plasma for transfusion) and blood products (e.g., a category of drugs called plasma protein and related products) to ensure quality and safety.

This first chapter of the Clinical Guide to Transfusion provides an overview of the blood system in Canada, including the regulations, standards, organizations and professionals that, together, help ensure a safe, secure and sustainable blood system for patients in Canada.

The federal government

The Canadian federal government is responsible for ensuring the quality and safety of blood components and blood products. Blood components and blood products are considered Schedule D drugs under the Food and Drugs Act, RSC 1985, c F-27. For decades, the collection, processing, testing and distribution of blood components for transfusion and for further manufacturing were regulated under the Food and Drugs Regulations, CRC, c 870. In 1992, the Drug Directorate Guidelines: Blood Collection and Blood Component Manufacturing, were issued by Health and Welfare Canada (predecessor of Health Canada) and provided reference standards and defined minimum criteria for facilities that collected and manufactured blood components outside of a hospital setting. In 1999, Good Manufacturing Practices for Schedule D Drugs, Part 2, Human Blood and Blood Components were issued by the federal regulator that provided specific guidance for the application of good manufacturing practices to blood operators. These guidance documents were followed by Canadian Blood Services and Hema-Québec for many years until they were rescinded. The manufacturing, importing and wholesaling of blood products (i.e., plasma protein and related products) are regulated under the Food and Drugs Regulations and are also subject to various Health Canada guidance documents that manufacturers, importers and wholesalers (e.g., Canadian Blood Services and Hema-Québec) follow.

The Canadian Standards Association (now known as CSA Group) published the first edition of a National Standard of Canada on Blood and Blood Components (CSA Blood Standard) in 2004.4,5 The CSA Blood Standard was published to guide establishments by providing management requirements for facilities that collect, process, test, store, and use human blood components for transfusion. It addresses issues of safety, efficacy, and quality for recipients, safety of donors, management of blood components, and safety of facility personnel and others who are exposed to or potentially affected by blood components.4 The Technical Committee for the CSA Blood Standard includes health professionals as well as representatives from the federal, provincial and territorial governments, user groups, and blood operators. In developing the CSA Blood Standard, the Technical Committee consults novel evidence and equivalent standards in Canada and other jurisdictions, including the AABB (Association for the Advancement of Blood & Biotherapies) Standards for Blood Banks and Transfusion Services and the Canadian Society for Transfusion Medicine’s (CSTM) Standards for Hospital Transfusion Services.

One of the Krever Commission recommendations was to amend the Food and Drugs Act to make the regulation of blood clear and in 2014, the Blood Regulations, SOR/2013-178, came into force along with a companion guidance document.6 The Blood Regulations apply to blood that is collected for transfusion or for manufacturing into drugs for human use. The Blood Regulations apply to establishments that collect, process, label, store, distribute, import or transform blood for transfusion and to establishments that collect blood for further manufacturing. Blood operators are required to submit operational changes to Health Canada and to demonstrate that the changes would not compromise recipient safety or sufficiency of supply. The Blood Regulations do not apply to cord blood and hematopoietic stem cells that are regulated under the Safety and Human Cells, Tissues and Organs for Transplantation Regulations, SOR/2007-118, to blood that is subject to clinical trials under the Food and Drugs Regulations or to blood that is imported for use in the manufacture of a drug for human use.

As part of its surveillance system, the Public Health Agency of Canada has established the Blood Safety Contribution Program (BSCP), which includes the Transfusion Error Surveillance System (TESS) and the Transfusion Transmitted Injuries Surveillance System (TTISS). The information collected through these voluntary surveillance systems is used to identify trends in transfusion-associated errors, adverse reactions and injuries in Canadian hospitals at the national level. They are also used as benchmarks for national and international stakeholders.7 Overall, these surveillance systems aim to improve transfusion processes and maximize patient safety.

The provincial and territorial governments

In Canada, the provincial and territorial governments (outside Québec) are responsible for the providing the financial support for Canadian Blood Services, their blood operator. The provincial and territorial ministers of health (except Québec) release funds annually that are required by Canadian Blood Services to operate for that fiscal year. Thus, while hospitals in these jurisdictions do not pay directly for blood components and blood products, their respective ministries of health allocate health-care funding for this. The money allocated to Canadian Blood Services by each province or territory is generally based upon their utilization of blood components and blood products.

The provincial and territorial ministers of health (excluding Quebec) elect the members of Canadian Blood Services’ board of directors, who oversee Canadian Blood Services. In addition, representatives from the provincial and territorial governments (excluding Quebec) are members of the Canadian Blood Services/Provincial Territorial Blood Liaison Committee (CBS PTBLC) and the National Advisory Committee on Blood and Blood Products (NAC), which have been established for the following purposes:

- The CBS PTBLC facilitates the work between the provincial and territorial governments (excluding Quebec) and Canadian Blood Services to support Canadian Blood Services in the provision of a safe, secure and affordable blood supply. The CBS PTBLC membership includes representatives from each provincial and territorial ministry of health (excluding Québec) and from Canadian Blood Services.

- The NAC is an advisory body that provides guidance on cost-effective utilization management of blood and blood products, and transfusion medicine practice to the provincial and territorial ministries of health (excluding Québec) and Canadian Blood Services. At the request of the CBS PTBLC, the NAC has developed a series of recommendations and guidelines on relevant topics, including recommendations for the utilization management of blood components and blood products in times of significant blood shortages. The NAC membership includes health professionals appointed by their provincial and territorial governments, Canadian Blood Services representatives, and a ministry of health representative.

Several provincial and territorial governments have established a provincial blood coordinating program to provide leadership and support to regional health authorities within their province. The provincial blood coordinating offices also serve as liaisons between the regional health authorities and the provincial governments regarding blood component and blood product management (See links to websites of the provincial blood coordinating offices).

Blood operators

The blood operators in Canada include:

- Héma-Québec, serving the province of Quebec,

- Canadian Blood Services serving provinces and territories outside of Quebec, and

- Grifols, authorized as of 2022 to operate within specific regions across Canada specifically to collect plasma and manufacture purified plasma products exclusively for Canadian use.

Blood operators are responsible for donor recruitment and selection, donation collection, testing, processing and the provision of blood or blood products to health-care facilities.

For Canadian Blood Services, qualified personnel with a wide range of skills and expertise (e.g., medical, nursing, laboratory technology, regulatory, legal, finance, IT, quality assurance, social science, epidemiology, marketing/recruitment, supply chain management), supported by a quality management system and facilities, ensure a supply of safe blood components and blood products that meet high standards of quality and safety.

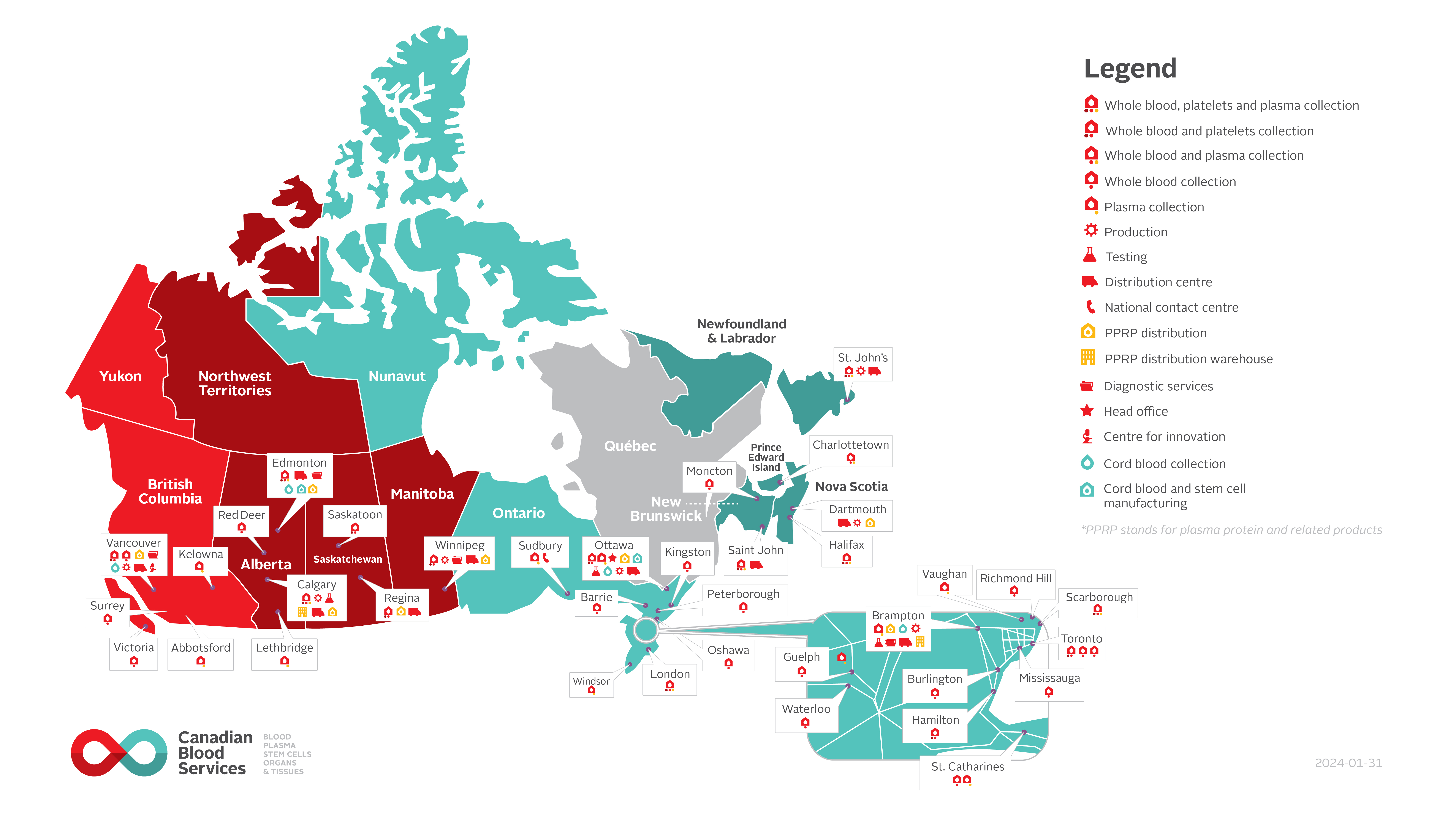

Figure 1: Canadian Blood Services’ operations map (last updated January 31, 2024)

Donor selection

As stated in the World Health Organization’s guidelines on assessing donor suitability for blood donation, “Blood transfusion services have the responsibility to collect blood only from donors who are at low risk for any infection that could be transmitted through transfusion and who are unlikely to jeopardize their own health by blood donation.”8 Guidance on donor selection has been incorporated into standards4 and blood operators fulfill this responsibility by establishing a rigorous donor selection process, which includes several steps, from educating prospective donors to screening potential donors (e.g., donor questionnaire related to acute illness and chronic infections) to obtaining post-donation information.9 However, donor selection decisions have a major impact on donor recruitment. See Chapter 6 on donor selection, donor testing and pathogen reduction.

Blood donors play an essential role during the selection process. Donors self-select to provide a voluntary gift and take on the responsibility of completing the screening questionnaire, undergoing assessments and testing as well as keeping the blood operator informed of any changes in their health.

Blood collection and testing

Blood operators are responsible for collecting whole blood and/or blood components from donors. Annually, Canadian Blood Services relies on blood donors from across the country to collect approximately one million units of blood and blood components at its collection sites. During the collection process, staff ensure donor wellness by monitoring for potential adverse reactions (see Chapter 6 for more on the blood collection process and the Canadian Blood Services Surveillance report for information on reported donor reactions). Staff also follow a set of policies and procedures to ensure the safety and quality of the blood collected.

Donor samples collected at the time of donation are tested for the presence of known transfusion-transmissible infectious agents using multiple screening tests that are performed in-house. Tests are either performed on all donations (e.g., HIV 1/2, hepatitis B virus (HBV) and HCV) or on a subset of the donations based on risk information obtained via the donor questionnaire (e.g., Trypanosoma cruzi, the pathogen which causes Chagas disease).10 More detailed information about donor screening and testing is presented in Chapter 6 on donor selection, donor testing and pathogen reduction.11

In addition to testing blood donors, Canadian Blood Services laboratories support transfusion practice by assisting hospitals with testing of patients with complex transfusion needs (see resources on red cell antigen genotyping, interpreting red cell antigen genotyping reports and testing for antibodies that may impact pregnancy management).

With the emergence of new pathogens and the development of new and improved tests (e.g., next-generation sequencing) and blood manufacturing technologies (e.g., pathogen inactivation; see Chapter 19 for more on the Cerus INTERCEPT pathogen inactivation system and the resources on solvent detergent treated plasma for more on the pathogen inactivation process used in solvent detergent treatment), blood operators must continuously reassess their donor selection and testing processes to ensure the safety of the blood supply while ensuring donor eligibility criteria are as inclusive as possible. Health Canada must approve changes made to donor screening and testing processes prior to the implementation of major changes. In recent years, the Alliance of Blood Operators (ABO), through the leadership of Canadian Blood Services, has developed a risk-based decision-making framework for blood safety to support blood operators in their decision-making process and facilitate proportional responses to risk.12 This framework has been used by Canadian Blood Services in the context of donor screening and testing, for example to assess the risks posed by Babesia microti, Zika virus, and malaria.

Blood component manufacturing and distribution to hospitals; wholesaling of blood products

Blood components are manufactured in the blood operators’ facilities. More detailed information about blood components manufacturing is presented in Chapter 2 on blood components.13

Plasma protein and related products and recombinant therapeutic products (blood products) are manufactured by pharmaceutical companies and wholesaled by the blood operators to health-care facilities in their jurisdictions. Canadian Blood Services also collects plasma which it provides to pharmaceutical companies to fractionate into purified plasma protein products. In addition, Canadian Blood Services negotiates contracts with pharmaceutical companies to provide appropriate fractionated and recombinant products to meet the needs of patients in Canada (see the national formulary for plasma protein and related products and Chapter 5 on concentrates for hemostatic disorders and hereditary angioedema).14

Blood components and plasma protein and related products are stored at Canadian Blood Services’ facilities and shipped to approximately 600 health-care facilities.

Retrieval/lookback and traceback procedures

Any information arising after the time of donation that may affect the product quality and safety must be reported to the blood operator. Such information can be received from many sources, including the blood operator (testing/medical/regulatory), donors, hospitals, and physicians. Canadian Blood Services receives information from hospitals that report an adverse reaction to a blood component (see Guide to reporting adverse transfusion reactions) and from donors who become unwell following a blood donation. All reports are investigated by Canadian Blood Services and, depending on the nature of the information, the following procedures may be initiated:

- Product inventory retrieval is a procedure established by the blood operator on a voluntary basis or mandated by the regulator, Health Canada. The procedure involves identifying blood components that could compromise recipient’s safety and removing them from the blood operator’s inventory. If the identified blood components have already been transfused, medical assessment and guidance from the National Advisory Committee on Blood and Blood Products is used to determine if recipient notification is required.15,16

- Traceback investigation is the process of investigating a report of a potential transfusion-transmitted infection (e.g., human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), hepatitis B (HBV), hepatitis C (HCV), West Nile Virus (WNV), Chagas disease) in a blood recipient. The purpose of the traceback investigation is to investigate any associated donors, obtain either negative (“clearing”) test results (from a subsequent donation) or identify a donor who subsequently has tested positive for that marker. When Canadian Blood Services learns that a blood recipient has tested positive for a transfusion-transmitted infection not otherwise explained, the implicated donor (or donors) associated with the transfused blood components are identified, located, and retested for the appropriate transmissible disease.

A traceback investigation may lead into a lookback investigation if a donor tests positive for the infectious agent and has previously donated blood.

- Lookback investigation is the process of identifying and contacting recipients of blood components from a donor who, on a subsequent donation or testing, is confirmed to have tested positive for the presence of a transmissible infectious agent (e.g., HIV, HBV, HCV, West Nile Virus, Chagas disease). When Canadian Blood Services learns that a blood donor has tested positive for a transmissible disease, a lookback procedure is initiated on that donor’s previous relevant donations. A recall procedure is initiated for blood components processed from these donations. Communication with hospitals and fractionators that received blood components and products from these donations is initiated to identify and notify recipients. Recipients are tested for the infectious agent found in the donor and Canadian Blood Services may be informed of the results.

For both lookback and traceback investigations, identifying individuals with positive tests for transfusion-transmitted infections is important for the safety of the blood supply. It is also essential for the donors and recipients so that they can receive appropriate follow-up. Donors may be indefinitely deferred following a lookback investigation, depending on the nature of the infectious agent. Canadian Blood Services provides a final report on all lookback and traceback investigations to Health Canada and shares investigation results in its annual Surveillance Report.

Hospitals

Hospitals play a primary role in ensuring that blood components and blood products are safely administered to Canadian patients in alignment with best medical practice. Depending on the size of the hospital, various frameworks may be in place; however, two main structures are generally considered:

- Transfusion laboratory staff (including transfusion medicine laboratory directors, transfusion medicine specialists, and transfusion safety officers) and medical directors manage blood components and blood product inventory and distribution to clinical staff. This group is involved in blood component compatibility testing to ensure an appropriate match between a blood component and a patient. They respond to lookback investigations, initiate traceback investigations and report adverse transfusion events. They are also responsible for guiding local transfusion practice as well as developing and implementing transfusion policies approved by the hospital or regional transfusion committee.

- Transfusion recipients’ ordering clinician (e.g., physician or nurse practitioner) order blood components or blood products for their patients in need. They are responsible for prescribing blood components and products according to standards and regulations.

Following the Krever Inquiry,3 Transfusion Safety Officer (TSO) positions were created within most major hospital centres across Canada. These transfusion-dedicated medical lab technologists or registered nurses are responsible for the quality and safety of transfusion within their respective institutions, particularly in the transfusion service and in the transfusing units, wards or clinics.

Hospital transfusion committees or regional transfusion committees were also established to oversee the transfusion activities of usually more than one hospital in a region. These committees provide consultation and support related to appropriate transfusion practice. Their multidisciplinary membership includes physicians, nurses, transfusion service staff, and executive management.4,17

In most jurisdictions, the applicable College of Physicians and Surgeons and/or the ministry of health also play an essential role in setting standards for laboratories, including hospital transfusion medicine laboratories. Laboratories performing transfusion medicine testing in these jurisdictions must be licensed and/or accredited and must abide by relevant provincial standards.

Under the Blood Regulations6 Health Canada exercises increased oversight on hospitals for some of the activities they perform that may impact the quality and safety of blood components. Hospitals who transform blood components (e.g., washing red blood cells and irradiating blood components) must be registered with Health Canada and are subject to regular Health Canada audits. Hospitals that store, distribute and transport blood components must also comply with certain provisions in the Blood Regulations, although there is no license/registration requirement for carrying out these activities.

Other organizations contributing to the blood system

Other organizations support the blood system in Canada by developing standards and guidelines as well as by supporting research and education.

The Canadian Society for Transfusion Medicine (CSTM) is an inter-professional, not-for-profit organization founded in 1979 (originally known as the Canadian Association of Immunohematologists) that promotes excellence in transfusion medicine in Canada. CSTM facilitates opportunities for education in transfusion medicine. Its flagship education program is the CSTM Annual Conference, organized by experts from the transfusion community in partnership with Canadian Blood Services and Héma-Québec. CSTM also plays a leadership role in the continuing development of standards by publishing the Standards for Hospital Transfusion Services, which reflects evidence-based best practice in Canada.17 Compliant with both the CSA Blood Standard and the Health Canada Blood Regulations, this publication supports safe transfusion practice in hospitals and assists in meeting accreditation requirements in some jurisdictions.

The Association for the Advancement of Blood & Biotherapies (AABB) is an international, not-for-profit association representing individuals and institutions involved in the fields of transfusion medicine and cellular therapies. The AABB develops standards for blood operators and transfusion services that provide additional guidance for Canadian institutions. In addition, the AABB has an extensive suite of educational resources that are relevant to the Canadian system.

As per one of the Krever Commission’s recommendations, advancing research is an essential element of a continued safe blood system. In Canada, Health Canada provides financial support to Canadian Blood Services for implementing a research and development program.18

The International Society of Blood Transfusion (ISBT), founded in 1935, is a scientific society which promotes research and knowledge mobilization through the organization of regional and international Congresses. The ISBT also advocates for standardization and harmonization in the field of blood transfusion. For example, it played a significant role in the development of the global standard for the identification, labelling, and information transfer of medical products of human origin (including blood components) known as the ISBT 128 labelling standard, which has been adopted in Canada.19 The other major impact of the ISBT on the transfusion community is the classification of various human blood group systems under a common nomenclature.

There is also the Biomedical Excellence for Safer Transfusion (BEST) collaborative, an international research organization, that explores ways to improve transfusion-related services through the standardization of analytic techniques, development of new procedures, systematic review of evidence, and execution of clinical and laboratory studies. Currently, the BEST brings together 42 scientific members, 8 manufacturing sponsors, and 20 blood service sponsors from 22 countries.

Collaborative environment

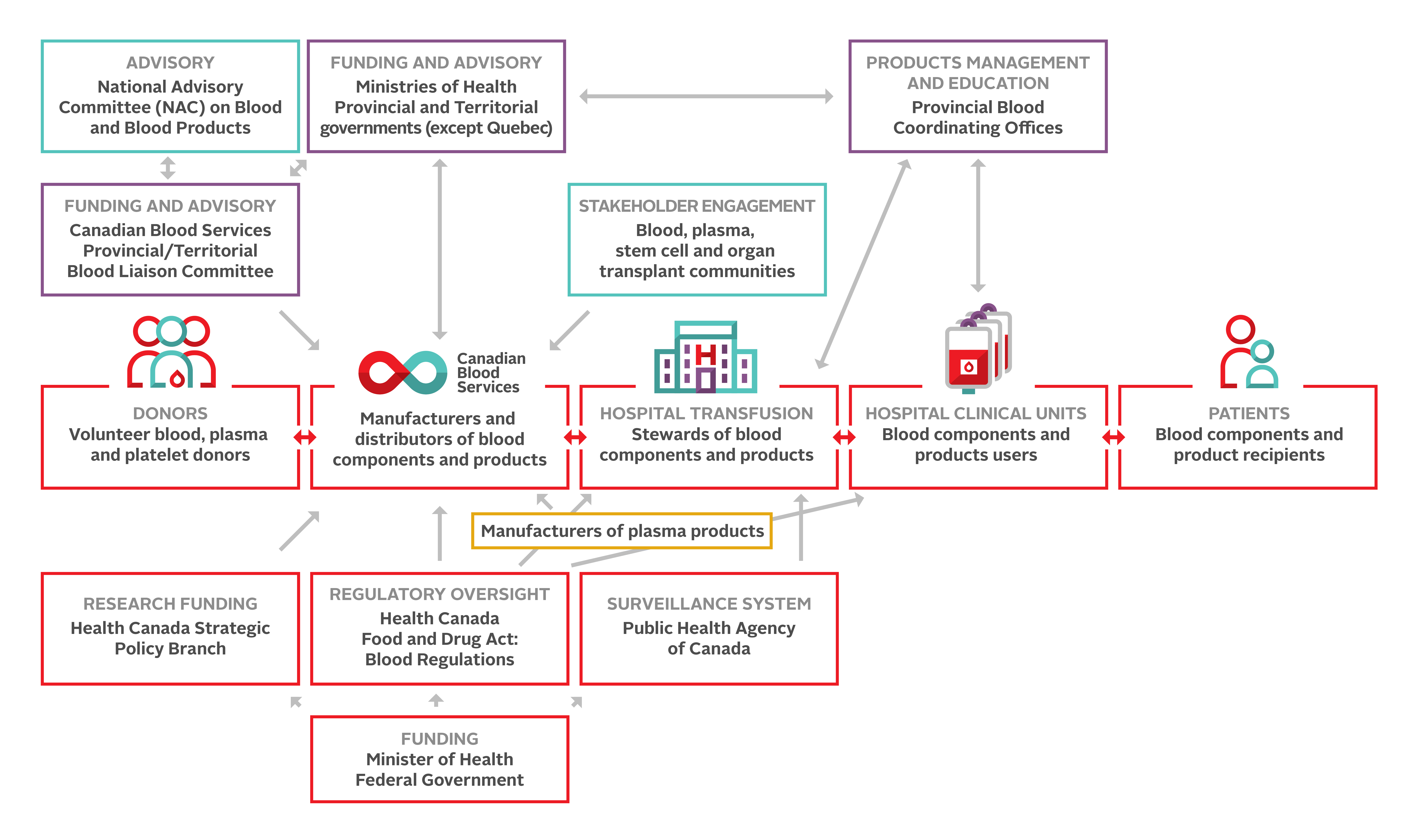

The interrelationships within the Canadian blood system are illustrated in Figure 2. The Canadian blood system relies on this framework to facilitate these relationships, and committed, competent and caring professionals contribute at all levels. Despite advances in ensuring the safety of the blood system, potential harms from transfusion remain and blood transfusion should never be considered to be without risk.

Decisions about blood utilization remain primarily a medical responsibility within Canadian hospitals. The processes of collection and testing of recipient samples, and the careful transfusion and monitoring of those receiving blood components and products, rely on health professionals. Continuing education for all involved in transfusion medicine remains critical.

Stakeholder engagement

Canadian Blood Services receives input from relevant and diverse stakeholder groups, including consumer groups, donors, patient/recipient groups, hospitals, health professionals, scientists, and ethicists.

Stakeholder engagement is the process Canadian Blood Services uses to gather input from its various audiences on policies, products, or operations. It involves listening, sharing information, engaging in dialogue, and exploring workable solutions for patients, families, caregivers, the broader communities we serve, and the health care system.

Engagement is a key pillar in Canadian Blood Services’ brand, and it’s how the organization involves stakeholders to make difficult, complex decisions collaboratively; or gather input to inform those decisions.

Continuing professional development credits

Fellows and health-care professionals who participate in the Canadian Royal College's Maintenance of Certification (MOC) program can claim the reading of the Clinical Guide to Transfusion as a continuing professional development (CPD) activity under Section 2: Individual learning. Learners can claim 0.5 credits per hour of reading to a maximum of 30 credits per year.

Medical laboratory technologists who participate in the Canadian Society for Medical Laboratory Science’s Professional Enhancement Program (PEP) can claim the reading of the Clinical Guide to Transfusion as a non-verified activity.

Suggested citation

Gabarin N, Yan M. Vein to vein: A summary of the blood system in Canada. In: Khandelwal A, Abe T, editors. Clinical Guide to Transfusion [Internet]. Ottawa: Canadian Blood Services, 2024 [cited YYYY MM DD]. Chapter 1. Available from: https://professionaleducation.blood.ca

If you have questions about the Clinical Guide to Transfusion or suggestions for improvement, please contact us through the Feedback form.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge Sophie Chargé who wrote the previous version of this chapter and thank Jennifer Davis, Patrizia Ruoso, Rosanne Dawson, Jon Fawcett, Jennifer Ciavaglia, and Tanya Petraszko, for their review of this chapter.

If you have questions about the Clinical Guide to Transfusion or suggestions for improvement, please contact us through the Feedback form.

References

1. Mulcahy, A.W., Kapinos, A.K., Briscombe, B., et al. Toward a Sustainable Blood Supply in the United States: An Analysis of the Current System and Alternatives for the Future. (ed. RAND Corporation) (Santa Monica, CA, 2016).

2. Picard, A. The gift of death: Confronting Canada’s tainted-blood tragedy, (Harper Collins, Toronto, Canada, 1995).

3. Royal Commission of Inquiry on the Blood System in Canada. Final report of the Commission - Commissioner: Horace Krever. Appendix H (Ottawa, Ontario, Canada, 1997).

4. CSA Group. CAN/CSA-Z902-15 - Blood and blood components, (CSA, Canada, 2015).

5. Canadian Standards Association Group. CAN/CSA-Z902:20 - Blood and blood components, (CSA, Canada, 2020).

6. Branch, H.C.H.P.a.F. Guidance document: Blood regulations. (Ottawa, Ontario, Canada, 2014).

7. Centre for Communicable Diseases and Infection Control. Transfusion Transmitted Injuries Surveillance System (TTISS): 2009-2013 Summary Results., Vol. 2016 (Public Health Agency of Canada, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada, 2016).

8. World Health Organization. Blood donor selection: Guidelines on assessing donor suitability for blood donation. (Geneva, Switzerland, 2012).

9. Goldman, M. Donor selection for recipient safety. ISBT Science Series 8, 54-57 (2013).

10. Goldman, M.D., S. J. (ed.) Blood donation testing and the safety of the blood supply, (Wiley Online Library, Hoboken, NJ, 2022).

11. Drews, S., Khandelwal, A., Goldman, M., et al. Donor selection, donor testing and pathogen reduction. in Clinical Guide to Transfusion (eds. Khandelwal, A. & Abe, T.) (Canadian Blood Services, ProfessionalEducation.blood.ca, 2021).

12. Leach Bennett, J., Blajchman, M.A., Delage, G., et al. Proceedings of a consensus conference: Risk-Based Decision Making for Blood Safety. Transfusion medicine reviews 25, 267-292 (2011).

13. Gupta, A. & Bigham, M. Blood components. in Clinical Guide to Transfusion (eds. Khandelwal, A. & Abe, T.) (Canadian Blood Services, ProfessionalEducation.blood.ca, 2023).

14. Poon, M.C., Goodyear, M.D., Rydz, N., et al. Concentrates for hemostatic disorders and hereditary angioedema. in Clinical Guide to Transfusion (eds. Khandelwal, A. & Abe, T.) (Canadian Blood Services, ProfessionalEducation.blood.ca, 2022).

15. National Advisory Committee on Blood and Blood Products and Canadian Blood Services. Recommendations for the notification of recipients of a blood component recall. (National Advisory Committee on Blood and Blood Products, 2015).

16. Petraszko, T., Tinmouth, A., Tran, A., et al. Recommendations for the Notification of Recipients of a Blood Component Recall: a NAC and CBS Collaborative Initiative (National Advisory Committee on Blood and Blood Products,, Ottawa, 2023).

17. CSTM Standards Committee. Standards for Hospital Transfusion Services, Version 4, (Canadian Society for Transfusion Medicine, Markham, Canada, 2017).

18. Office of Audit and Evaluation Health Canada and the Public Health Agency of Canada. Evaluation of the Health Canada Canadian Blood Services Contribution Programs 2013-14 to 2016-17. (ed. Government of Canada) (Ottawa, Ontario, Canada, 2018).

19. Armitage, J., Ashford, P., Bolton, W., et al. ISBT 128 Standard - Technical Specification v5.9.0. (ed. Cabana, E.) (ICCBBA, San Bernardino, CA, USA, 2018).