Dr. Donald Branch honoured by AABB for his career achievements

Dr. Donald Branch’s career shows a scientist driven by intellectual curiosity. From Gila monster venom to crocodile blood, from HIV to Ebola to huge discoveries improving outcomes for transfusion and transplantation patients, he pursues scientific questions and embraces all the twists and turns that path of inquiry may take.

“There’s always something new that keeps the interest going,” he says. “It’s pretty hard to figure out nature — it has a way of throwing a wrench in things just when you think you have an answer. Then you have to keep looking. There’s always a new angle, a new hypothesis, that keeps you from getting bored.”

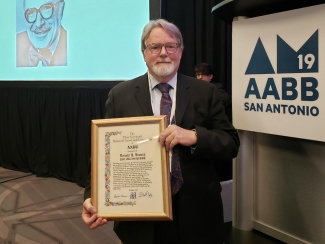

Last month, Dr. Branch, a scientist at Canadian Blood Services’ Centre for Innovation and professor at the University of Toronto, received a prestigious international award honouring his more than 40 years of major contributions to transfusion medicine and hematology.

At this year’s annual meeting of AABB, an international organization representing people and institutions involved in transfusion medicine and cellular therapies, Dr. Branch received the Tibor Greenwalt Memorial Award. It’s his third award from AABB, but he says he isn’t in it for the accolades.

“As a scientist, we don’t do our work thinking we’re going to get any awards. I do my science because I like it. It’s fun, interesting and exciting at times; and you get to think of new questions about what is important in biological sciences and how things work,” he says.

“It’s nice to get an award, because it says what you’ve been doing for fun these last 40 years has paid off — people have found value in it. You have to have a thick skin in research. You have to be able to accept rejection and criticism, especially when you’re writing grants and papers. The work itself is interesting and exciting, but trying to advance the field can be difficult. When you actually get an award for something you’ve done, it’s meaningful because it represents years of hard work and overcoming some of the criticisms and roadblocks along the way.”

Dr. Branch’s proudest accomplishment is being the first scientist to describe mixed hematopoietic chimerism, a state where after a bone marrow transplant both the recipient and donor’s cells exist together harmoniously in the blood. Published in 1982, Dr. Branch’s finding has been confirmed and generated more than 1200 related publications. Where there is mixed hematopoietic chimerism, there is little if any graft-versus-host disease, and this fact has led other scientists to explore this phenomenon for recipients of other types of transplants, such as hearts, livers, lungs, and kidneys. Introducing mixed hematopoietic chimerism into transplant recipients may lead to them not needing anti-rejection medication.

“The general thinking at the time was that following bone marrow transplantation where myeloablation (a severe reduction in the ability of a patient’s bone marrow to produce new blood cells) was the protocol, if you begin to see the blood cells increasing in population, you’ve obtained engraftment of the donor stem cells. I found this wasn’t necessarily true. You could have the patient’s own stem cells come back and repopulate the patient, sometimes with no donor cells detectable for long periods of time; so, more genetic testing needed to be done to determine which cells, the patient’s or the donor’s, or both were coming back. This finding was something very new; this was the first time it had been reported,” he says.

What’s next for Dr. Branch? He has many projects on the go, including one investigating whether HIV/AIDS could be a neuropeptide disease, and another looking at a little-understood phenomenon in some sickle cell disease patients. Many sickle cell patients require regular blood transfusions. After a red blood cell transfusion, hemoglobin levels typically increase and taper off gradually over time. Hyperhemolysis is a life-threatening reaction to blood transfusions in sickle cell patients where instead of staying increased, hemoglobin increases briefly, then crashes lower than even the initial level. This can happen within a matter of hours, and with further transfusions it can happen repeatedly.

“We don’t know why this happens to some patients, so I’m working to figure out this mechanism,” says Dr. Branch. “If we know why and how this happens, maybe we can figure out how to prevent it.”

Canadian Blood Services – Driving world-class innovation

Through discovery, development and applied research, Canadian Blood Services drives world-class innovation in blood transfusion, cellular therapy and transplantation—bringing clarity and insight to an increasingly complex healthcare future. Our dedicated research team and extended network of partners engage in exploratory and applied research to create new knowledge, inform and enhance best practices, contribute to the development of new services and technologies, and build capacity through training and collaboration. Find out more about our research impact.

The opinions reflected in this post are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the opinions of Canadian Blood Services nor do they reflect the views of Health Canada or any other funding agency.